A group of four progressive attorneys — three public defenders, one civil rights attorney, all women — is making a historic push to diversify the Los Angeles Superior Court, an institution heavily populated by former prosecutors and corporate lawyers, and by men.

The self-described “Defenders of Justice,” Holly Hancock, Elizabeth Lashley-Haynes, Carolyn “Jiyoung” Park, and Anna Reitano, have campaigned together, hoping to claim four of the nine seats up for election in LA County this year, with backing from the Transforming the Judiciary Coalition.

Four local advocacy organizations make up the coalition: La Defensa, the LA chapter of the Working Families Party, Court Watch LA, and Ground Game LA.

In addition to diversifying the bench, the coalition hopes to change the obscure nature of the judicial election system so that it is more accessible to voters.

In California, local superior court judges serve terms of six years, and voters elect new judges during elections in even-numbered years. In reality, however, nearly all sitting judges vacate the bench mid-term, leaving California’s governor to appoint their replacement. Those replacements rarely face challengers in the final year of the term they’ve stepped into.

When someone does challenge an incumbent judge, or when a vacancy goes unfilled, it’s up to voters to decide who will fill the seat.

However, unlike candidates for most other races on the ballot — sheriff, lawmakers, local officials — judicial candidates rarely campaign. Some candidates don’t even have campaign websites. This means voters are often left ill-informed about who is running, and of the high stakes involved.

There are 499 judgeships in the LA Superior Court system. They preside over civil law, adult and juvenile criminal law, family law, child welfare, LA’s unique mental health court, small claims and traffic court. These judges are empowered to make decisions that can drastically alter the lives of those that come before them — decisions about bail, about appropriate sentencing, about whether parents get to keep their children, about whether teens will be sent to juvenile lockups or kept in their communities.

What happens when defenders become judges?

Having more public defenders and civil rights attorneys on the bench, advocates believe, will lead to a more just system.

A May 2022 Harvard study suggested that former public defenders serving as judges presiding over federal criminal cases were less likely than judges from other backgrounds to hand down sentences that included incarceration. And former defenders were less likely to give extremely long sentences (of 30 years or more) than their colleagues.

The study included data from 740,786 charges handled by 1,381 different federal judges between 2010 and 2019.

Political scientists Allison Harris and Maya Sen, the report’s authors, point out that public defenders are likely to be more conscious of the high personal cost of incarceration on defendants, and of defendants’ “relative lack of power,” when compared to that of prosecutors.

At the federal level, Harris and Sen wrote, “consistently appointing former public defenders would reduce the number of people incarcerated and, potentially, prison sentence length … a subtle shift would result in thousands of fewer sentences of incarceration per year.”

LA County voters have never elected a public defender to the bench.

While the governor does appoint some public defenders to counties’ court systems, LA County residents have never voted a public defender into the superior court.

(This year, the U.S. Supreme Court gained its first former public defender in Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. The dearth of former defenders remains a problem in California’s high court and in other state supreme courts, too. Yet, the Harvard study suggests that California voters want more judges with defense and civil rights experience on the nation’s federal benches, and presumably in our local courts as well.)

Few defense attorneys, in general, are elected, leaving LA’s superior court bench populated mostly by former prosecutors and corporate attorneys, who tend to represent the wealthy and powerful.

“Over the past 20 years, we have had 11 elections where over 78 percent of the winners had a prosecution background,” said Gabriela Vazquez, Deputy Director of La Defensa, at a press conference in May. “We have almost exclusively elected district attorneys and prosecutors to sit in our family courts, in our juvenile courts, our small claims and traffic courts. Those trial courts are where most Angelenos come into contact with the judicial system for the first time.”

Additionally, Vazquez noted, only 38 percent of LA Superior Court judges are women.

“Los Angeles is a diverse community, and they deserve to have diversity on the bench,” said Holly Hancock, who is running for Seat 70 against three prosecutors and a volunteer traffic and family law judge. “Think about who you want to see when you come into the courtroom.”

Hancock is the Deputy-In-Charge of the Criminal Record Clearing Unit of the LA County Public Defender’s Office. Her clients, she said, sometimes come up against judges who are unwilling to clear even decades-old convictions that keep people from accessing housing and employment opportunities. Hancock and the other defenders say they have a different view of what community safety should look like.

“It’s the Defenders of Justice against the status quo,” said Hancock, who is endorsed by the LA County Democratic Party, the LA Times, and the LA County Public Defenders Union. (See the rest of Hancock’s endorsements here.)

In addition to three of the “Defenders of Justice,” there are three more people with public defense experience running in the June primary: Kevin McGurk, Lloyd Handler, and Patrick Hare.

“This is a historic judicial election cycle for L.A. County,” tweeted the LA County Public Defenders Union, which endorsed all running public defenders. (The union did not endorse the lone civil rights attorney in the Defenders of Justice, Carolyn “Jiyoung” Park, opting not to make a recommendation for Seat 118 or the other two seats for which no public defenders are running.)

“There have never been this many public defenders on the ballot,” the union continued. “We have witnessed for years how many judges are resistant to evidence-based reforms to the criminal legal system and the harm this causes to our clients.”

As with other offices up for election, a judicial candidate must get more than 50 percent of the popular vote during the primary election on June 7, to avoid a November runoff.

Correction: This story originally identified Anna Reitano, Holly Hancock, and Elizabeth Lashley-Haynes as former public defenders. These judicial candidates are still working in the public defender’s office while campaigning, however.

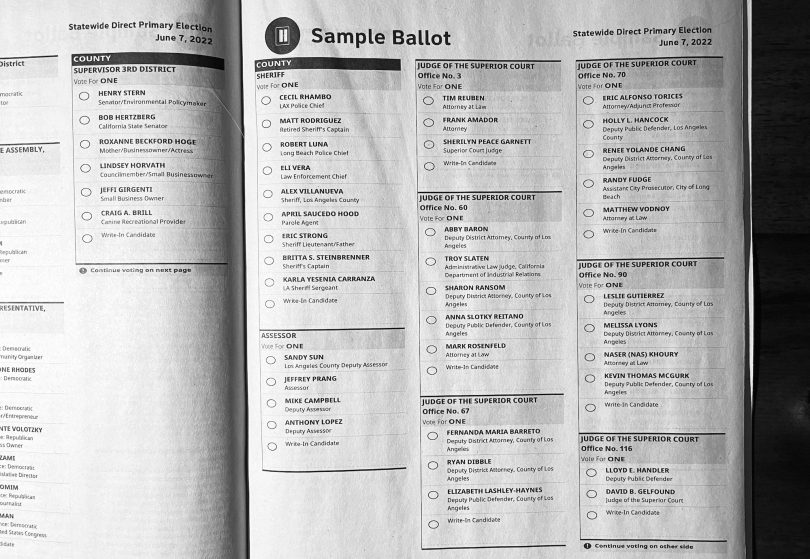

Image: LA County sample ballot for June 7, 2022 primary election.