In a new report just released by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, researchers describe the worsening conditions inside the state’s still remaining youth prisons.

The Department of Juvenile Justice — or DJJ — as the California’s youth prison system is called, will be shuttered completely and permanently by June 30, 2023.

In an effort to wind down the system toward its closure, on July 1, 2021, the state shut off the pipeline to prevent any additional youth admissions from California’s various counties

Even so, all of DJJ’s facilities are still open, including one in Ventura County (nicknamed Ventura), two in Stockton (called Chad and O.H. Close), and a fire camp in Amador County (known as Pine Grove), and conditions in the first three especially, are becoming more problematic, not less, during the wind down, acc.

It doesn’t help that the facilities, which were built decades ago, “still use the outdated model of sparse, prison-like cells or large open dormitories with concrete walls and razor wire,” write the report’s authors, Maureen Washburn, Renée Menart, Tatum O’Sullivan, Madelin Orr, and Leighanne Guettler-James.

This new report, is one of an ongoing series by CJCJ, which has become the de-facto oversight entity for the state’s long troubled youth lock-ups.

In February of 2019, for example, CJCJ published a deeply researched and scathing report about DJJ, in which the authors described the disturbing climate of violence and fear that breeds trauma in already traumatized youth, and where a recent spike in attempted suicides and high rates of youth injuries, are among the indicators that raise urgent red flags about the emotional and physical safety of the kids living inside DJJ’s three aging facilities.

Yet as bad as the facilities have been in the recent past, now that the system is winding down, the brand new report describes the many alarming ways that conditions in DJJ youths’ living units have reportedly become increasingly deteriorated, physically and psychologically.

Bad becomes worse

The problems include “rusty or broken bathroom fixtures, poorly functioning air conditioning systems, and mold growth in the showers.”

Despite the worsening physical conditions, and the theoretical wind down to closure, the facilities still have a lot of kids in residence.

As of June 2021, write the report’s authors, Chad still held 254 youth in these conditions that reportedly continue to get worse, O.H. Close had 139, and Ventura had 225 — according to the CDCR’s own numbers.

(For anyone who has forgotten, CDCR stands for California Department of Correction and Rehabilitation.)

Another issue, according to the report’s authors, is the fact that, with the looming closure of the facilities, staff are starting to elect to “transition out,” creating a new problem of staff shortages.

(Nearly one-quarter — or 22.52 percent — of DJJ’s budgeted staff positions were vacant in June 2021 compared to 16.88 percent in June 2020.)

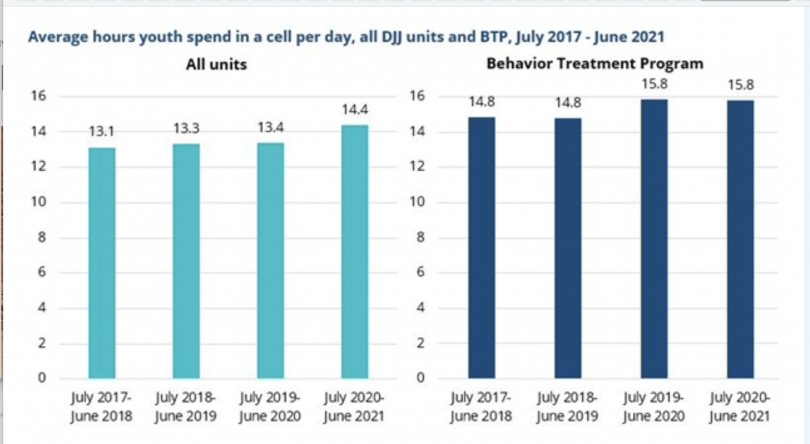

Fewer staff, in turn, means, significant cuts to rehabilitative programs, causing youth to have to spend an unhealthy amount of time confined to their their cells, which now totals an average of 14.38 hours cell-time per day.

When youth are outside their cells, conditions are reportedly growing every more violent and generally “unsafe,” say the CJCJ authors.

Of course, the distressing lack of safety for the youth who live in the facilities is not a new problem.

In the 2019 report, the researchers described the DJJ facilities as being plagued by “a culture of violence.”

Yet, according to the new report, the staff shortages, and the slashing of programming, has measurably worsened the situation to the degree that, during the period from July 2020 to June 2021, approximately 19 youth out of every 100 was “involved in or affected by a violent incident.”

The violence, in turn, precipitates additional use of force on the part of the stressed-out staff, which, in turn, “traumatizes youth and erodes staff-youth relationships,” wrote the new report’s authors.

Things have gotten so bad that DJJ’s use of force incidents were investigated at a rate nearly 10 times higher than the rate for California’s adult prisons.

The deleterious effect on the youth of this emotional toxic environment is then demonstrated by the veritable flood of incidents of suicidality.

“With a population averaging approximately 700 youth,” the authors write, “DJJ reported 467 total instances of suicide risk from July 2020 to June 2021.”

Specifically, between July 2020 and June 2021, there were seven suicide attempts and 467 total instances of suicidality within a population averaging just over 700 youth, according to CDCR records. In other words, an average of five young people attempted suicide or were reported as being at high risk for suicide out of every 100 youth in the facilities each month.

The reentry problem

Another demonstration of DJJ’s ongoing failure is its chronic inability rehabilitate and heal the youth in its care, in order that they might redirect their lives in a healthy and productive direction when they get out. This failure continues as it continues to move toward its closure.

So how bad are DJJ’s reentry outcomes? Within three years of release, over three-quarters of youth returning from DJJ were rearrested, half were convicted for a new offense, and nearly 30 percent returned to state custody.

This is not a new problem, but like the other markers in the new report, during this new period of slow motion closure of the youth lock-ups, things have assuredly not improved.

“Coming home from DJJ, you have nothing,” said a youth interviewed in 2021 by CJCJ researchers for the new report.

“No reentry plan. Nothing. Yeah, my PA [Parole Agent] and my counselor made a little reentry plan on paper, but they’re not familiar with my geographic region… so what they put down is the bare minimum. [When] I came home, I was really on my own. That’s my situation right now. I’m trying to make all that negative into a positive.”

The very near future

So, what to do?

In less than two years, the authors remind us, DJJ will close its doors, “bringing an end to a system that has endangered generations of youth.”

Yet, similar harms to those that the CJCJ researcher/authors have described in their newest report exist, to greater and lesser degrees, throughout the various youth justice system in California’s counties, including in Los Angeles County.

The latter fact was made clear approximately two months ago when, as WitnessLA reported, the California Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) voted unanimously that Los Angeles County Probation’s two juvenile halls — Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall and Central Juvenile Hall — were out of compliance when it came to multiple basic standards of care. Thus, these two facilities were declared “unsuitable for youth habitation.”

In other words, the two youth halls, were not safe places for kids to be living. Period. Full stop.

Meanwhile, the ongoing discussions between LA County Probation and other relevant stakeholders about what constitutes a healthy and healing environment for the county’s youth who, in the past, would have been sent to DJJ — and where and how such an environment could be located — are far from settled.

In the midst of this major transition, the CJCJ authors warn, “California must heed the lessons of DJJ’s failure,” and make sure that DJJ is not merely “replicated at the local level.”

Instead, they say, this historic closure “offers California the chance to reinvest state dollars into what keeps youth safe: vigorous oversight, alternatives to secure facilities, and a platform that uplifts the voices of California’s youth.”

Yes. And it would be a good thing if LA County could manage to seize that opportunity, and lead the way.

More as well know it.