The Los Angeles Police Department has a partnership in an unusually effective diversion program for youth that, according to both the cops and juvenile advocates, seems to really work. Now the LAPD hopes to expand the program citywide. But that will take money, which no one has, as yet, offered to pony up.

The partnership is called the Juvenile Arrest Diversion Program, or JADP. It keeps kids who qualify out of the juvenile system if they break the law. The six-month program with a six-month follow-up instead diverts them into an alternate system where they face the human consequences of their actions, while at the same time being connected with individually tailored services and activities designed to help each youth recalibrate the direction of his or her life.

At the June 6, Los Angeles Police Commission commission meeting, all five commissioners listened intently to a detailed presentation about the JADP program, accompanied by a written report from LAPD Chief Charlie Beck. And by the end of the meeting, everyone seemed convinced of the worth of the program, but without an immediate solution for the cost of the full expansion.

Both the report and the presentation had been requested two months earlier by police commissioner Shane Goldsmith, who wanted a public accounting of the JADP program that detailed exactly how it worked, how many kids it served, its success rate, how much it cost.

Goldsmith who, along with being a police commissioner, is the president and CEO of the Liberty Hill Foundation, and a longtime youth advocate, said she felt “LA should be leading the charge” when it comes to finding models that help kids who are struggling.

“So when I got on the police commission, I asked around to find out what the department was doing to help kids, and I discovered this program that’s like a hidden treasure….that is having wild success rates, so officers love it. And the department loves it!”

Goldsmith also found that, despite its success, the program was still in some ways in its pilot phase. As a consequence, she wanted “to shine a public light” on the unique LAPD diversion partners, “so others could get involved and work on it, and help to expand it.”

The strategy seemed to have had an effect, since part way through the June 6 meeting, the LAPD’s First Assistant Chief, Mike Moore, (the guy who is the highest on the department’s food chain, next to Chief Beck) announced that the department planned to expand the diversion program citywide by the end of the year.

If, they can get the resources.

The Birth of the Program

The LAPD’s partner in the diversion program is Centinela Youth Services (CYS), which has been around helping youth and their families since the 1975.

In 1999, CYS began something called the Victim Offender Restitution System or VORS, which got a law-breaking young person together in mediation with the victim of his or her actions. The program allowed the youth to understand the impact of his or her behavior, and allowed the victim to get some kind of restitution, which varied from getting actual money, to having chores done for a given time period, or some other exchange to which both the youth and victim agreed.

The program, which became a national model, worked so well that in 2011, CYS applied for and got an important $1 million grant to start a newer version of the VORS program.

The highly competitive grant, which came from the Everychild Foundation, allowed CYS to launch the Everychild Restorative Justice Center right next to the Inglewood Juvenile Court, to provide “intensive clinical case management and comprehensive community-based intervention programming to divert youth from the juvenile court system.”

Everychild’s president and founder, Jacqueline Caster, an attorney turned juvenile justice advocate (who is also now on the LA County Probation Commission), wondered if this diversion program could begin before the youth was actually arrested. She’d seen the results of a similar program in Florida, called the Miami-Dade Youth Assessment Center, which is credited with helping drop youth crime in that area of the state.

In fact, with the Miami-Dade model in mind, a few years prior to Everychild’s 2011 grant to CYS Caster decided to personally explore whether or not the notion of a community-based nonprofit partnering with the police held any interest for local law enforcement. In 2009, she contacted then LAPD Chief Bill Bratton, who was getting ready to leave LAPD post. Bratton told her he liked the program, and would pass on the idea to soon-to-be-chief, Charlie Beck.

Thus, when CYS got its $1 million from Caster’s Everychild, the first tracks for a working relationship with the cops had already been laid.

In 2012, CYS got a second $1 million grant, this time from the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC), which allowed them to open a second diversion center, this time in South Los Angeles, with agreements from the LA juvenile court system, and the LA District Attorney’s office.

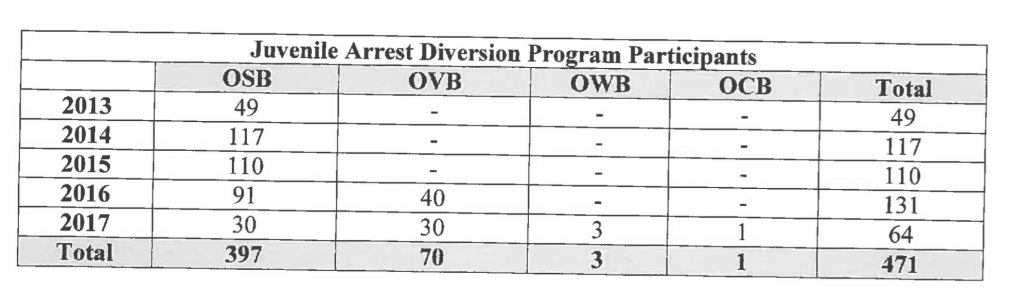

Finally, in 2013, after after two years of meetings, the LAPD became a fully active partner. JADP began pilot programs in the department’s Southeast and 77th Street divisions. Southeast was important, according to the report to the commission, because juvenile offenses were occurring in that station’s territory at a higher rate than much of the rest of the city.

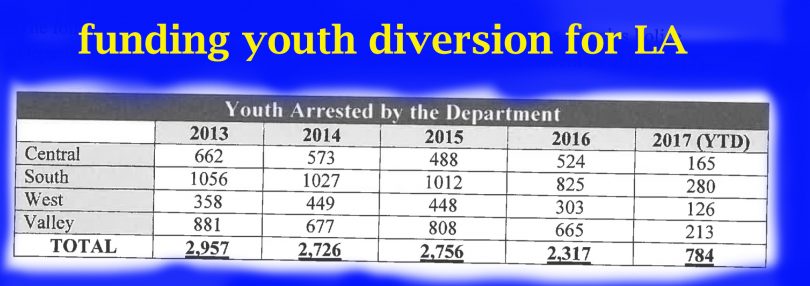

In 2015, the program migrated to all of South Bureau. In 2016, Valley Bureau joined the party with three of their divisions: Mission, Van Nuys, and Foothill. This year, West Bureau came in as well.

Originally the program got its referrals from juvenile court or occasionally probation, Jessica Ellis, the director of Centinela Youth Services, explained to the commission.

“But once the LAPD came on board,” Ellis said, “we began doing what we call ‘pre-booking diversion,’ which means when a kid is detained, the booking is put on hold. “There is no fingerprinting, no booking.” Furthermore, if the kid completes the program, then the arrest vanishes.”

This is important, Ellis said, because it means that when the juvenile becomes an adult an arrest, even though it never became a conviction, can really stand in their way.”

And so it was that, according to the report and to Ellis, CYS’s Juvenile Arrest Diversion Program (JADP) became the first pre-booking juvenile diversion program in the state of California.

Since 2013, the Los Angeles Police Department has referred 471 kids to the program.

Misdemeanors, Felonies, and the Teenage Brain

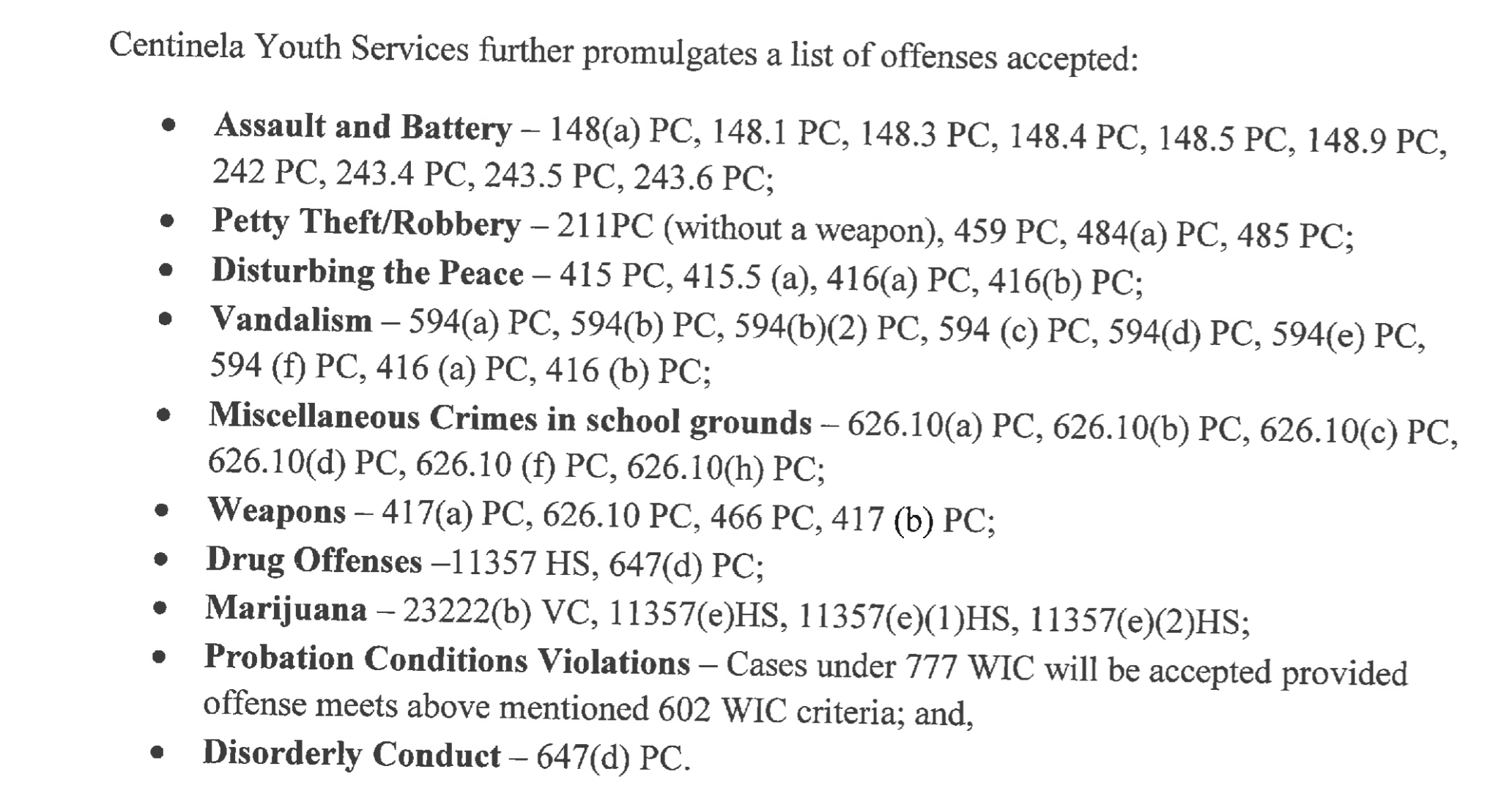

The kids who are eligible for the program must be under eighteen and with “minimal priors.” This means the youth need not be first time offenders—but what they’ve done must fall into a particular range of offenses, according to Ellis.

“A lot of other programs only take misdemeanors,” said Ellis. “But we can go all the way up into felonies, because of our [success] record.”

Big, bad felonies like rape, kidnapping, armed robbery or worse are excluded.

The program bases much of its strategy on the most up-to-date research on the teenage brain, Ellis explained. For example, “teens are hard-wired to rebel against adult authority. That’s their job at that age.”

So to interrupt the pattern of knee-jerk rebellion, CYS sets up face-to-face meetings between the adolescent and his or her victim. “So that they have to sit down and hear about the impact of their actions,” she said. Then they also have a voice in coming up with an activity that will do what is possible to make things right.

Sometimes, the victim “will also have made assumptions about the kid that are not correct.” So the interaction builds empathy and understanding for both sides, Ellis said. It also allows the emotions related to the crime to be dealt with. And those things are “what leads to a change in behavior.”

The other key part of the system, according to Ellis, is “engagement of the community.” With this in mind, the meeting between kid and victim is facilitated by volunteers from the immediate community who go through special training. “That way it brings the responsibility for juvenile justice solutions back into the community,” which empowers that community, said Ellis.

Along with the meetings with victims, the program works to get each youth what he or she needs in the way of help and support, like mental health services, activities, classes, and the like.

Interestingly, the victim satisfaction for the mediation process is around 98 percent, and 96 percent of the youth report that the feel the mediation process is a fair one.

Getting Buy-In From the Cops

The collaboration between the LAPD and CYS goes beyond just the fact that the cops agree to put a hold on arrests for kids who hit the right legal marks for the program, and then refer them to CYS. The CYS people, the LAPD, plus representatives from the DA’s office and probation, also meet to talk through policies, procedures and outcomes bi-monthly.

I was also important, at the partnership’s beginning, to help cops change assumptions, Ellis told the commission. “So we started doing trainings [with officers] on the teenage brain, and the affect of trauma on behavior, understanding defiant behavior…” and so on.

“We saw a lot of arrests where kids didn’t start out with illegal behavior, but the reactions of the adults led that kid to escalate.”

CYS was also careful not to force the program on rank and file officers. “We asked captains not to mandate buy-in to the program when CYS is first working with a new division,” Ellis said. Instead, CYS staff held meetings with patrol officers, detectives and others, and asked them to talk about all the things they didn’t think would work. “We tell them ‘Don’t be nice to us!'” said Ellis.

In one division, a detective gave them a kid with the caution, “Good luck with this one!”

But, said Ellis, “when that kid came back, turned around, suddenly we had real buy-in with that division.”

What About Success Rates?

Most importantly, the strategy appears to work with the kids it serves.

According to Ellis, a few years ago, a study compared kids who completed the CYS/JADP program with kids who went through the county’s conventional juvenile justice system, and found that the CYS kids had a 15 percent recidivism rate after 1 year, as compared with the justice system kids 31 percent recidivism rate “for comparable crimes and circumstances.”

Now CYS is down to 11 percent recidivism after one year, and with some groups of kids the recidivism drops to 7.8 percent, as compared to the county’s 26 percent. ”

For kids confined in the county’s juvenile system, said Ellis, the recidivism rate goes up to 60 percent.

Cost Per Kid

The cost of helping kids via the LAPD CYS partnership ranges from under a thousand for lower risk kids, to as high as $4500 or $5000, a kid for those with more complicated needs, according to Ellis.

But those prices are for the “ramp-up” years, she said, when the program was in its start-up pilot phase, and thus pricier. Once it’s rolled out across the city, and in a “maintenance” phase, she said, “we believe we can get the cost-per-kid down below $2000.”

According to the most recent numbers WitnessLA has acquired, for middle school and high school age kids on formal probation in Los Angeles County, the cost is $6,298 per kid per year, with a far worse statistical outcomes.

And for the kids locked up in a county juvenile facility, the dollar amount per kid per year is a startling $552 per day in a probation camp, which means $201,480 a year, for one kid. For kids residing in LA County’s juvenile halls, the price tag is: $640 per kid per day, or $233,600 a year.

And, for the highly controversial “voluntary probation” program we reported on last month that serves 7,560 at risk LA County youth, who have committed no crimes, the cost per kid per annum is $1,480.55, with at least $1,017 of those dollars going to pay the salaries of probation officers, who reportedly provide little in the way of actual services.

COMPSTAT and Other Feedback Loops

Captain Jeffery Bert, who is the LAPD point man for the program, said that “in 21-years” of service to the department, “nothing has been more important” to him that the experience of leading the youth programs unit, oversees the diversion partnership.

Among the next steps, according to Captain Bert, is a plan to include the CYS program in the department’s well-known COMPSTAT program in order to measure the diversion program outcomes, “and where that might”match up with crime reduction,” Bert said, the same way the department does with crime stats and arrest clearances.

The LAPD also wants to institute a “feedback loop for officers who refer kids,” according to Bert, so they can find out what happened to those kids. “It’s the missing piece,” he said. “The cops who work juvenile divisions really care about kids. And yet they never hear what happened to the child—because of confidentiality rules, and life goes on. But it’s important,” Bert repeated. The officer thinks, “‘I didn’t get to put handcuffs on him, so then what happened?’ They need to know.”

Where the Rubber Meets the Road

By the end of the commission meeting, there appeared to be no question that the Los Angeles Police Department genuinely wants to expand the restorative justice diversion partnership.

“It’s representative of a way of engaging with our communities in a way other than law enforcement,” said Assistant Chief Moore. “So we’re asking for the ability to deepen it.”

But serving more kids will take more money. CYS and the department figure that, if the program is running across just LA City (which is not including the areas policed by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department), roughly 20 percent of all juvenile arrests would qualify as referrals.

There was a long pause at the meeting as that number sank in.

“But expansion of this program is critical to the future of this city,” said commission V.P. Steve Soberoff suddenly. “Because you look at the people you don’t serve, and you see what they cost us, and what they go on to do to the community. And the ones you do serve go the other way…You’re a huge off-ramp of the freeway to jail!” Another pause. “And it works. It works everywhere.”

So will the City of LA find a way to fund this freeway off-ramp?”

Will LA County find a way to help too by, say, yanking some dollars out of its piles of unspent juvenile justice mattress money, or perhaps out of, say, the budgets of programs that have, as yet, not been proven to do much good?

Well….stay tuned.

What about the kids who are on the cusp of being arrested and their parent know they’re spiraling out of control. What’s their on-ramp into the program.