On Tuesday, the LA County Board of Supervisors will consider a motion to create a “Voter Engagement Taskforce, with the goal of registering justice-involved Los Angeles County residents in advance of the November 2018 general election.

If the motion passes, in addition to registering the aforementioned voters, the job of the task force will be to create an informative, encouraging PR campaign featuring posters, websites, and public service announcements, on the value of civic engagement and voter rights for justice-involved people. The task force will also track participation to see how they did.

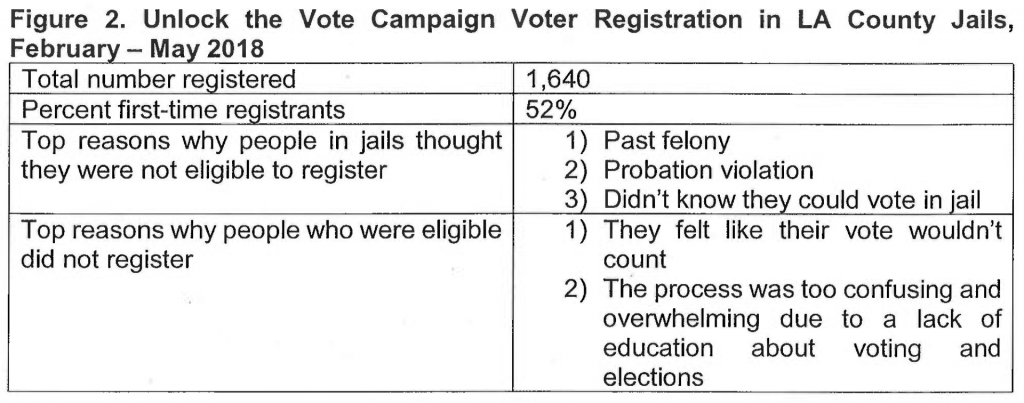

Tuesday’s motion, authored by Supervisors Mark Ridley-Thomas and Sheila Kuehl, is part of a sequence of events that began with an earlier Ridley-Thomas motion passed in February, which triggered a report by the county’s Director of the Office of Diversion and Reentry (ODR), former Los Angeles Superior Court Judge, Peter Espinoza, along with a list of others, to develop a countywide plan for voter education and registration of eligible justice-involved youth and adults, that built on an existing “Voting While Incarcerated” program led led by the Registrar Recorder’s office and County Counsel, with community-based organizations such as Susan Burton’s A New Way of Life Reentry Project, and the ACLU of Southern California’s rigorous Unlock the Vote effort inside the LA County and OC jails, to get people ready to vote in the June primaries.

In June, the Espinoza and the county CEO came back with her report, which suggested the task force was the best next step in getting this group of thousands of potential voters registered and to the polls in November.

Who has the right to vote in CA?

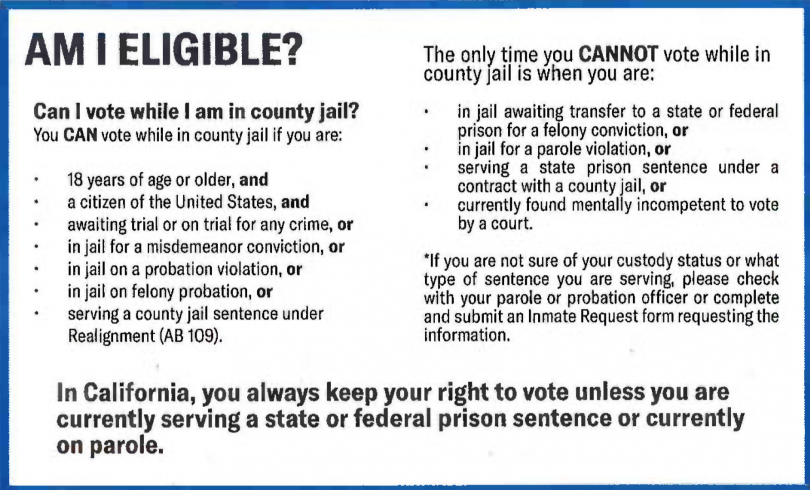

Whether or not one can vote after being convicted of a felony varies from state to state. In the State of California, citizens are not allowed to vote if they are serving time in a state or federal prison, or if they are still on parole for the conviction of a felony.

Once one is out of prison and off parole, one may register to vote right away.

People in jail may register and vote if they are serving a misdemeanor sentence (a misdemeanor never affects your right to vote), or if they are on probation, or in jail as a condition of probation, or serving a felony sentence in jail, or in jail awaiting trial.

Those on probation or some other form of county, community, or federal supervision (that is not state parole) may also vote, according to the California Secretary of State.

Those citizens locked-up for non-serious felonies serving time in county jails or under county supervision through California’s prison realignment (AB 109), are also allowed to vote, a right that was clarified and affirmed by AB 2466, a bill Governor Jerry Brown signed in 2016.

Since all this is a little nuanced, many people with felony and misdemeanor convictions are unsure if they can vote or not, thus some solve the problem by not dealing with voting at all.

With Tuesday’s motion, Kuehl and Ridley-Thomas hope to sweep away those kinds of fears that lead people to shut themselves out of civic involvement.

“Civic engagement and voting are the cornerstones of democracy,” their motion states. “Engaging all individuals in these efforts, including those with justice system-involvement, is critical. Voter engagement also serves as an important reentry and crime prevention strategy.”

Voting and recidivism

An array of studies and reports suggest that Ridley-Thomas and Kuehl are right in the claim that voter engagement can reduce recidivism.

One of the most interesting reports–albeit not the most definitive—was done in Florida, which has some of the strictest prohibitions about ex-felons voting. Basically, a felony conviction means one loses one’s voting rights for life, except for the few brave souls that go through the complex and infrequently successful process of applying to have their rights restored through clemency.

In any case, here’s what the numbers crunchers in Florida found about restored voting rights and recidivism.

The average recidivism rate in Florida from 2011-2015 has hovered around 30 percent. Yet, during that same five year period, in 2011, of the 52 people granted voting restoration, zero were returned to custody. In 2012, out of the 342 people giving their rights back, only one re-offended. In 2013, out of 569 people, zero re-offended. In 2014, of 562 people granted voting rights, three re-offended. In 2015, out of 427 people, one re-offended.

To put it another way, of the 1,952 people whose civil rights were restored, five committed new offenses, an average recidivism rate of 0.4 percent.

Obviously, those who apply to have their voting rights restored are generally a self-selecting subset of former felons. But, although this set of numbers doesn’t provide enough data to draw anything close to conclusive correlations, the stats are intriguing. And other more academic studies suggest similar patterns.

Artwork related to voting and civic engagement by detained young people in LA County Probation youth programs

The joy of voting

Since I have written about criminal justice issues for nearly 28 years, I’ve often been around when people whom I’d gotten to know in the course of my reporting got their voting rights back.

It has always been a thrilling thing to hear tales about their experiences with casting their votes, often for the first time in their lives.

In November of 2012, for example, Prop 36—the state initiative to reform California’s Three Strikes law—was on the ballot, and one guy I knew named Wil, who worked for Homeboy Industries, posted on Facebook about his about-to-be-newly-minted-voter excitement the day before voting day arrived on November 6.

“Wow,” Wil wrote, “it’s been over five years and I never thought this day will come but I can honestly say I’m doing my part. I’m voting tomorrow, first time in my life, I’m f***ing voting tomorrow. Please, friends, go out and vote. Help make a change!”

Luis Aguilar is another man who’d been to prison, whom I know well and, who, like Wil, was extremely happy to be voting that November, and particularly thrilled to be able to cast his ballot for Prop 36.

A former gang member, in the years since his voting rights were restored in 2004, Luis has done well working union jobs on massive city and county construction projects, and is both an excellent dad and husband.

On that Tuesday night in 2012, he called me from his job site to ask if I knew how the various ballot propositions were faring.

“Some guys deserved to be there,” he told me, referring to three-strikers he’d known in prison. “But for other guys I saw, it was just a waste of taxpayers’ money.”

Luis worked the night shift that year so he and his wife had voted before he left for the job. He was relieved when I told him it looked like 36 was winning.

“I had this cellie one time when I was locked up who got struck out for stealing three pairs of Levis from Sears,” Luis said. “His other strikes weren’t nothing violent either. He was just an addict, and when he was using he did stupid stuff.”

When Luis first voted in 2004, I was writing a series of articles for the LA Weekly about him and his family during his first year out of prison. I remember the seriousness with which he took his newly acquired enfranchisement then, a seriousness that appeared now to have only deepened—–as demonstrated on voting night in 2012 when he called multiple times to ask for updates.

He was most interested in Prop. 36, but wanted to know about rest too, especially Prop. 30, Gov. Brown’s then new sales tax raise to benefit education, which Luis strongly favored.

“I voted against everything else that the voting pamphlet said would cost the state more money,” he said. “But on 30 I voted yes, because schools are important.”

In terms of candidates, he voted a straight Democratic ticket, Luis said. “The only time I didn’t look at parties was for DA, then I voted for the lady—–I don’t remember her name…”

“Jackie Lacey.”

“Yeah. That’s right. Because I liked the way she talked better than the guy, who looked like he mostly wanted to show he was all tough.”

“It feels good to vote,” I said to Luis before we rang off, the very last time he called that night. “It matters.”

“Yep,” he replied. And with that I heard his county-issued walkie-talkie squawk in the background. He thanked me for my help, and he had to go.

Update

On Tuesday, the vote by the board was enthusiastically unanimous to move forward with the task forces.

Fresh baked lasagna. Apple pie with real vanilla ice cream. 3 pairs of clean cotton socks. 2 inches of new polyurethane foam replaced in the vinyl mattress covers.

If Sheriff McDonnell times this correctly, he could win an important captive swing voting bloc in November.