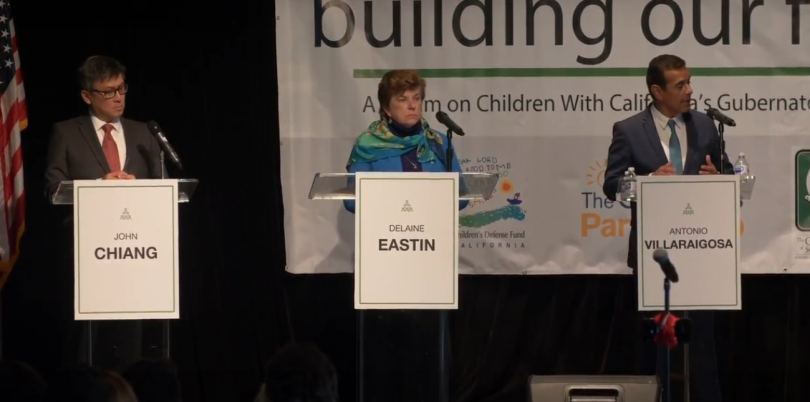

At LA Trade Technical College, during what was billed as the first forum or debate among California’s gubernatorial candidates focused solely on children’s issues, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, California Treasurer John Chiang, and former State Superintendent of Public Instruction Delaine Eastin discussed education, health care, immigration, juvenile justice, and foster care.

Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom, the current frontrunner to take over from the termed-out Governor Jerry Brown, has missed many opportunities to debate his fellow candidates over the past few months—save for one debate on May 8—and his absences have garnered criticism from the other contenders.

Also missing from the lineup was Republican John Cox, a businessman, who appears to be neck and neck with Villaraigosa for second place in the polls, and Assemblyman Travis Allen (R-Huntington Beach).

“I think showing up matters,” Villaraigosa said of the absent candidates. “It shows respect for all of you, and for the issues at hand.” Thanking his fellow panelists, Villaraigosa said Chiang and Eastin were the two people on the campaign trail that he saw “again and again.”

The event was hosted by The Chronicle of Social Change, Children’s Defense Fund-California, and The Children’s Partnership, along with Los Angeles Daily News, LA School Report, and others.

And while Newsom was absent from the forum Tuesday evening, he and his fellow candidates answered questions posed by the event organizers prior to the event.

The Issues at Hand

Without any of the Republican candidates or Newsom, there wasn’t much disagreement among the three Democrats on the stage, who nevertheless, had specific things to say about improving the state of foster care, juvenile justice, and education for California’s kids.

“California is home to 60,000 foster children, more than any other state in the nation,” moderator and founder of the Chronicle of Social change, Daniel Heimpel, said to the candidates, prefacing a round of child welfare and juvenile justice questions. “It serves more than 29,000 children and youth caught up in its juvenile probation system.”

Juvenile probation is an enormously costly system in California. Despite sky-high spending, the juvenile justice system often fails kids who come into contact with it. “Here in Los Angeles, one in three youth will be arrested within a year of being released from a probation camp,” Heimpel said, asking candidates what they would do to improve recidivism rates and outcomes for probation-involved kids.

“We have an absolute moral dilemma here,” Eastin said, regarding the state of incarceration in the United States. “Ladies and gentlemen, you’re spending $75,000 per year, per prisoner,” in California. “We’re number one” in locking people away in jails and prisons, Eastin said, but number 41 in per-pupil education spending. “We need to get our priorities straight…too many children are being incarcerated when they should be receiving counseling” and other supports.

The state can address juvenile justice system issues, according to Villaraigosa, through education and “targeted and proven intervention methods,” the former mayor said, pointing to his efforts as LA Mayor in starting Summer Night Lights, and the LA Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development.

“For juveniles in the system who have committed serious and/or violent felonies that require intensive treatment services, we have to resource mental health services for them and work closely with counties to make sure our youth are being served in every area of the state.”

Chiang pressed the importance of addressing justice-system-involved kids mental health and substance use needs, “to make sure those individuals are not committing the same types of crimes over again and that they are working with the system to get the treatment and recovery they need.” The state must also “help incarcerated young people get the education and life skills they need so when they leave prison, they don’t resort back to a life of crime,” Chiang said. “Finally, we need to make sure that when these young people re-enter society, that they continue to have access to services that give them a fighting chance,” and that their families receive supportive services, too.

In his pre-forum interview, Newsom focused his attention on childhood trauma and trauma-informed care. “We know that the ACEs research shows that incidents of childhood trauma impact children for a lifetime, including setting them up for disproportionate interactions with the criminal justice system,” Newsom said, referring to Adverse Childhood Experiences questionnaire—which asks questions about abuse, neglect divorce, and other experiences, and is the benchmark for measuring trauma in youth.

“As governor, I will be an advocate for community schools, whose comprehensive approach to meeting students where they’re at, including helping to address traumatic circumstances such as homelessness, makes a real difference,” Newsom continued. “I will also continue to be an advocate for prevention programs that help at-risk youth stay out of the criminal justice system, as well as rehabilitation and diversion programs that help nonviolent criminals become contributing members of society.”

California must also “make sure that we don’t fall into the trap of treating the symptom rather than the cause of this problem,” according to Newsom. “It’s no surprise that study after study shows just how debilitating growing up in poverty is to a kid’s potential in life,” and how it relates to lower academic achievement, and increased liklihood of homelessness and incarceration. “If we want to prevent at-risk youth from entering the criminal justice system in the first place, we need to invest in policy solutions that equip low-income families and their children with the foundation they need to succeed,” Newsom said. “As governor, eliminating childhood poverty will be my administration’s north star.”

The Candidates Talk Equity in Education

Villaraigosa said he when he was mayor, he was “the education mayor, and if elected governor, he would be known as “the education governor.” The former LA mayor has received a much-needed funding boost of more than $13 million (now up to $22.5 million total, just behind Newsom’s $26.5 million) from rich charter school supporters, including Netflix co-founder Reed Hastings and philanthropist Eli Broad, in just a month.

“California is doing great things in the area of school climate,” a moderator said, directing a new question toward Villaraigosa. “Suspension rates dropped for all students from 5.7 percent in 2011-2012 to 3.6 percent in 2016-2017. However, the disproportionate impact on African American students has not declined in that same time period, and they are still three times more likely to be suspended than white students.” What policy and funding strategies, then, would Villaraigosa turn to for “greater racial justice in education,” during this “era of Black Lives Matter?” the moderator asked.

“I went to a high school that, when I graduated in 1971, had a 25 percent graduation rate,” the former mayor said. More than 30 years later, the same school had a 36 percent graduation rate. Now, the school has an 81 percent graduation rate.

Villaraigosa was a high school dropout who, according to the former LA mayor, changed his trajectory with the help of his mother and a teacher who believed in him, and by being given a “second shot” by the state.

Villaraigosa said that he was “heartened” by the governor and state legislature’s efforts to better serve “high-needs” students.

In the past, California’s education budget allocation was severely inequitable. More money was often given to affluent school districts, short-changing the schools (and the students) that needed the state’s financial support the most.

In 2013, to address the problem, California enacted the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), a weighted funding approach that allows districts, rather than the state, to decide how a portion of their funding is spent. The formula aims to level the playing field for high-needs students who are severely underserved by school districts.

The LCFF sets aside extra money for high-needs kids—specifically kids from low-income households who qualify for a free or reduced-price school lunch, kids who are learning English as a second language, homeless students, and foster children. These kids make up nearly 60% of the total LAUSD population. The formula requires districts to set up goals and action plans for helping vulnerable students transcend achievement gaps and barriers with regard to attendance, suspensions and expulsions, and interactions with school police.

Villaraigosa said the LCFF money gets “spread like peanut butter,” rather than going to the students with the most needs.

Los Angeles has certainly struggled with LCFF, according to a report from United Way of Greater Los Angeles. While LA Unified School District has increased allocated money for high-needs middle and high schoolers, it has failed to properly distribute funds for high-needs elementary students.

Villaraigosa said that he would employ better data collection to replicate the successes of the districts that are getting LCFF right, identify and incentivize best practices, and work to ensure that the money goes to the kids that need it most.

In the past, Chiang has cautioned against throwing more money at the state’s education problems without holding anyone accountable. Moderators asked Chiang whom should be held accountable and how.

Accountability, Chiang said, should be at the individual school site level. Parental involvement is important, and families should be getting support from principals, vice principals, and other school leadership. “All it takes is one person to impact a child,” Chiang added.

Newsom called California’s education system “fragmented” to the point of “stymying” efforts to help the state’s highest-need students. “We need to end this era of inefficiency by linking early childhood, K-12, higher education, and workforce data systems to more productively identify what practices are working and where our resources should be deployed,” Newsom said. “Streamlining this information will help usher in a new era of accountability. LCFF made high-needs students a priority in policy, but the hard work of implementation to truly serve students’ diverse needs is still a struggle with limited resources.”

Eastin said that the “elephant in the room” in discussions about LCFF is a serious dearth of school funding. “They’re rearranging the deck chairs on the titanic,” Eastin said. The firmer state superintendent said she is “glad to see” more money set aside for the kids who need it most. And while LCFF and accountability account for a “step in the right direction,” California needs to be putting way more money into education in general. “If you’re near the bottom on spending, don’t be surprised if you’re near the bottom on achievement,” Eastin added.

Eastin, who is 70, said that when she was growing up in San Francisco, she went to “fine public schools.” Back then, California was tied for fifth place with New York on education spending among the 50 states. Now, CA spends less than half as much as NY, and is ranked number 41 in per-pupil spending, according to the California Budget and Policy Center, which used 2015-2016 data, adjusted for each state’s cost of living. “Shame on us,” Eastin said. “We’re dead last in the number of nurses, counselors, librarians.” The former state superintendent called for more spending from maternity leave and prenatal care, to free full-day kindergarten, to free community college. “Education should be a priority for every elected official in this state,” Eastin added. “The future will be decided by what kind of education, child development, and care will be given to them. We are falling behind. I pledge to you, I’ll put the children first again.”

Improving Child Welfare in California

Chiang, when asked about preventing child abuse and neglect, said that the state must do better to make sure that California’s kids can grow up free from abuse, neglect, and poverty, in a safe environment. “We must strengthen our social safety net to lift all our families up and give every child a safe place to grow up,” Chiang said in his pre-forum interview. “This includes parent education and in-home visiting to give parents support, knowledge and guidance about raising a child. Parents should have somewhere they can turn to for support when things get tough, before it escalates to abuse or neglect. And when all else fails, we need to provide our foster care system with the resources necessary to ensure our children have a safe place to go if their parents or guardians cannot take care of them.”

Eastin reiterated her call for education and support for parents as a preventative measure. Additionally, the state needs “a more nimble child abuse detection and avoidance system,” according to Eastin. “As Governor I would call on our great public and private research institutions to join with leading practitioners in California’s welfare system to draft a strategic plan to dramatically improve our child welfare system,” Eastin said. “We would ask this Child Welfare Task Force to suggest legislative enhancements to our child welfare system to dramatically reduce child neglect and enhance child welfare.”

Newsom, too, called for better preventative supports for parents. “The ACEs research makes clear the lifelong consequences for child neglect, and the need to support parents in a dual-generation strategy,” Newsom said. “I will expand and strengthen the parent engagement strategies proven to support child health and safety, including family nurse visits, one-stop family resource centers and community schools, and parent support programs.”

Villaraigosa knows from experience, the effects of abuse on children. “I am a survivor of domestic abuse and have stood for children and women suffering from domestic violence my entire life,” the former mayor said. “I know what it’s like to be 5 years old and feel helpless – I couldn’t do anything to stop it then, although I did later.”

Villaraigosa pointed to his past work on the issue, including the creation of Safe LA, and said that if elected governor, he would “take this work much farther.”

Neglect and abuse are closely tied to other issues, including problems with school and the law, Villaraigosa said. “For me, I had anger issues and that led to trouble in school,” Villaraigosa continued. “So there is a nexus here to our school system, our public safety and criminal justice system, and to our shared responsibility to not only stop violence from occurring, but for caring for those who have suffered.”

The measure of a good school is successfully educating students, but also having the “resources it needs to face the realities of their home life,” according to Villaraigosa. “A good system for dealing with juvenile offenders is not one that gives up on them – it treats the underlying issues that drive behavior. And a good state is one that is generating good jobs that support stable families and generate revenue needed to fund critical programs for those in need.”