A UNIQUE YOUTH DIVERSION PROGRAM HOPES TO HELP MORE KIDS RESTART THEIR LIVES

If Only LA County Probation Will Fork Over the Promised Funding

by Jeremy Loudenback

When Karina Cabrera first sat down with Angelica,* a 15-year-old enrolled in Centinela Youth Services juvenile diversion program, the case manager remembers the youth’s icy stare and clipped answers. (* “Angelica’s” name has been changed to protect her privacy.)

Just weeks before, Angelica had been hauled in by members of the Los Angeles Police Department after she was caught trying to steal a shirt at Target.

This was Angelica’s first offense, but the teenager from South L.A. was quickly heading down a problematic path. She had recently flunked most of her classes and her school attendance was dwindling down to nearly nothing. According to Cabrera, Angelica’s father has been in and out of jail during much of her life. Angelica had a rocky relationship with her mother, who offered little encouragement or support to her daughter. As a consequence, the girl was spending most of her time on the streets where she found the support she was looking for, but with the wrong people.

“She was trying to fill the void that wasn’t getting from mom and dad,” Cabrera said.

“Members of a gang were the only ones who showed her love.” When the two met, Angelica “couldn’t envision a future for herself that didn’t involve being part of a gang.”

After the attempted Target theft, however, the police offered Angelica and her family a novel choice: If she completed a six-month program with Centinela Youth Services—a program based in Inglewood, Calif., that includes victim restitution and therapeutic services—she could walk away without any trace of the incident on her record.

In the past, low-income youth in communities like South L.A. have had few options after getting arrested. Being picked up by the cops for law-breaking usually meant a booking number, a day in court, fees, and mandatory weekly meetings for the next year or so with a probation officer. Or worse, it could mean weeks or months in a juvenile probation facility.

But thanks to a unique pilot project created in partnership with the Los Angeles Police Department’s South Los Angeles bureau, Centinela Youth Services (CYS) has given more than 300 at-risk youth a year—and the law enforcement officers who arrest them— an alternative. Using a philosophy that incorporates the emerging science of adolescent brain development, the CYS diversion program is poised for expansion. But Los Angeles County’s failure to distribute state funds related to community-based juvenile justice programs has cast doubt on the future of the program.

The only pre-arrest juvenile diversion program in the state, CYS has earned acclaim from local officials for the low recidivism rate of its graduates. According to the organization’s numbers, between 8 and 11 percent of youth who come through CYS are arrested again in the year after the completion of services. This mark is much lower than the return rate for youth who are processed though the county’s probation system.

According to a 2015 study of juvenile probation outcomes conducted by a team of researchers headed by Cal State L.A.’s Denise Herz, youth who are part of L.A. County’s system of probation camps, juvenile halls and group homes have a recidivism rate of 33 percent a year after youth exit their placements. Other estimates have pegged juvenile recidivism rates in Los Angeles County as even higher, at up 40 percent.

After concluding a three-year pilot project last year with two LAPD stations in South Los Angeles—the Southeast and 77th stations—CYS is now poised to open a second program in the San Fernando Valley, in partnership with the LAPD’s Foothill and Van Nuys stations.

“The pilot showed us it’s a win-win situation for the youth and the county,” Supervisor Sheila Kuehl said. “If you can help a young person turn their life around, you’re going to save a lot of money down the line. You’re not going to have consistent juvenile offenses, you’re not going to have an adult offender.

“You’re going to have less recidivism. That’s what we’re aiming for.”

REIMAGINE JUVENILE JUSTICE IN LOS ANGELES

Ever since advocates convinced LAPD Chief Charlie Beck to give the program a shot in 2012, Deputy Chief Bob Green has been a staunch supporter.

Green started his more than 30-year LAPD career working as beat cop in South Los Angeles in 1980. His early years on the job coincided with the rise of the crack cocaine epidemic and the attendant spread of gang violence, which impacted the lives of thousands of L.A. youth of that era.

Before being transferred to the Valley Bureau last year, Green spent years policing South Los Angeles. Green transitioned from the streets to leading anti-gang efforts as commanding officer of the 77th station and then later he headed up the entire South Bureau.

During his years working in South L.A., Green said he noticed with dismay that kids arrested at a young age too often found it difficult to break free of the system after that first arrest.

“Once I give that at-risk kid a booking number, that’s very hard to recover from,” Green said. “Sometimes that means a death sentence in South L.A.”

Green said that the long-term consequences of a police record can discourage many youth from changing their less-than-healthy behaviors, further entrenching their relationship with the justice system. And once they’re in the system, he said, there’s often very little in place to steer youth back to a more hopeful life.

Los Angeles County Deputy District Attorney Kerry White might agree. When he started crunching numbers from the county’s juvenile court system soon after he started working in the DA’s juvenile division in 2010, White found a disturbing trend.

Now the head of the DA’s juvenile division White saw that at least 60 percent of kids at almost every one of the county courts had more than one case, and a large number had three cases or more.

“That told me that just appearing before a judge as a minor was not enough to turn a kid’s life around. We needed something more,” White said.

With the blessing of former DA Steve Cooley and current DA Jackie Lacey, White helped broker the terms of the CYS program in 2012. Now, all misdemeanor and felony charges for youth between ages of 9 and 17 are eligible for Centinela’s diversion program, with the exception of more serious offenses like rape, murder and the use of firearm (legally referred to as 707(b) offenses).

Since the program is aimed at youth who have recently entered the system, participation is limited to young people who have committed their first or second offense. (The program occasionally includes third-time offenders if the prior charges were minor.) Youths who are arrested for robbery, assault and drug sales are eligible, pending the discretion of the police.

The LAPD continues to refer juveniles with a more serious history of gang involvement to the city’s Gang Reduction and Youth Development (GRYD) program, where youth can receive prevention and re-entry services. But options have been limited for lower-income youth arrested in Los Angeles for minor offenses like petty theft.

Even arrests that don’t go to court are still logged in to the juvenile automated index, a Los Angeles County Probation Department system that tracks a youth’s involvement with the court.

Once a youth is part of the system, the impact can be felt for years, according to Centinela Youth Services Executive Director Jessica Ellis. Joining the military is a popular way out of South L.A. for many youth, she said, but just one arrest can discourage those dreams. And much later, a youth’s record on the juvenile automated index can pop up in licensing applications and background checks for careers as nurses, contractors and pharmacists.

“It’s holding a lot of them back,” Ellis said.

ADAPTING THE MIAMI MODEL

The CYS program was adapted from a similar program in Miami that also involved partnerships with law enforcement agencies, the juvenile courts, community-based organizations, and others.

At CYS, after an arrest, eligible youth are screened to determine their needs, then linked to services such as tutoring, counseling, mentoring, substance abuse treatment and parenting classes. For instance, CYS refers many youth in South Los Angeles to the Brotherhood Crusade, where they can participate in mentoring and other youth development programs

Adapting the idea to L.A. proved difficult at first. Initially, referrals from law-enforcement agencies were slow to arrive. Part of the issue was that it was difficult to find many first- and second-time offenders who fit the bill. Even by the age of 15 or 16, staff at CYS found that many youth had already accumulated too many arrests to qualify for the program.

Centinela and their LAPD partners retuned their program. Now CYS accepts youth as young as young as 9 years old, part of an attempt to intervene earlier in the cycle of youth who at risk of entering the justice system—at a fraction of the cost of more expensive—and life-altering—incarceration options down the line.

WHO WILL FUND CHANGE?

Centinela Youth Services was able to launch its first restorative justice center in Inglewood with a $1 million grant from the Everychild Foundation.

Jacqueline Caster, president and founder of the Everychild Foundation and a Los Angeles County Probation Commissioner, said that she and her board members were attracted to the program that they believed provided an opportunity for kids in trouble that wasn’t being offered elsewhere in the county.

“When it was first pitched to us, it was compelling to hear that you can have these different results, save money and save lives,” Caster said. “And it makes a lot of sense to deal with issues on the front end rather than the back end.”

Later, CYS used money from state a grant for juvenile delinquency prevention to establish another center in South L.A., near the LAPD’s 77th station.

But long-term funding is a challenge, even for a program with a success rate like Centinela’s.

CYS supporters are hoping that a pot of state dollars earmarked for community-based juvenile justice programs will offer the long-term sustainability that has up until now eluded the program, but the needed money is far from assured.

Under the 2000 Juvenile Justice Crime Prevention Act (JJCPA), California counties receive a total of more than a $100 million a year that each county is supposed to use for prevention and early intervention programs, and services aimed at keeping youth out of the juvenile justice system.

L.A. County Probation received approximately $26 million last year in JJCPA funding. But oddly the county has failed to spend a huge portion of its money. As a December 2015 audit showed, LA’s probation department has been sitting on nearly $22 million of JJCPA funds accumulated over the past four years.

(WitnessLA reported on the hidden cache of cash, which at first probation declined to admit existed, here and here.)

After news of the unused juvenile justice dollars came to light last July, the Board of Supervisors directed that $5 million of the hoarded cash be put in the hands of the Board, with $1 million allotted to each supervisorial district.

Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas, whose district includes most of South L.A., pledged his $1 million to support the CYS’s programs in South Los Angeles. Supervisor Kuehl has committed half of her allotment—$500,0000—to CYS in order to expand the juvenile diversion programs in the San Fernando Valley.

More than six months later, however, the funds have yet to be actually allocated, leaving CYS’s long-term prospects still up in the air.

ADDRESSING TRAUMA IN SOUTH LA

CYS case manager Cabrera realized that she would have to build a relationship with Angelica before the troubled teenager could make further strides.

“She was trying to get a sense of what type of person I was and why I was there,” Cabrera recalled. “Early on, I really had to remind her about my role and why she was in the program.”

Case manager Cabrera realized that making a real difference with Angelica would require more than just a quick hand-off.

Cabrera and the rest of the staff at CYS hoped that they could help Angelica imagine a future that didn’t involve becoming gang affiliated. But first Cabrera would have to find a way to help Angelica deal with the issues that lay at the root of her risky behaviors —such as a sense of abandonment and a lack of positive role models.

“The underlying issues had been occurring for so long that they were just passing by [the adults in her life],” Cabrera said. “Nobody noticed or was providing the services to deal with the issues and the trauma she was experiencing.”

CYS Director Ellis said that roughly a third of the youth who come through the organization’s two centers are directed to services that address the significant personal trauma that has either directly or indirectly contributed to problematic behaviors, as was the case with Angelica. Another third, said Ellis, are managing an undiagnosed or unaddressed mental health issue, like a severe anxiety disorder, depression or PTSD.

She told of a youth who had been expelled from school for fighting just hours after learning that his much-loved grandfather had died. Other kids cope with trauma caused by repeated incidents of violence in their neighborhoods, or in their ruptured families. Still others have been removed from their families and placed for years in the county’s foster care system where they felt they belonged to no one.

When youth are referred to CYS, a case manager like Cabrera is charged with making a visit to the child’s home to perform a screening designed to locate areas in which youth are in need of counseling and other supports.

Conversation with a kid starts with questions like, “Have you experienced any loss or ]has someone close to you passed away in the past 90 days? Have you left school for no reason? Are you having difficulty paying attention at home or school?”

High-risk youth like Angelica who demonstrate a need for further services are connected to mental health programs and intensive clinical case management that can stretch across six months, and sometimes even longer.

Unwilling, at first, to talk about her past, it took three or four months before Angelica would agree to therapy. Cabrera met with her at least three times a month and checked in with her by phone in between, listening uncritically, building rapport, having conversations about healthy relationships and setting goals.

“One day, she said, ‘I want to have to have a healthy way of thinking,’” Cabrera remembered. “After gaining so much trust with her, she finally felt that someone cared, that someone was listening to her, and she agreed to the services we both knew she needed.”

Recently, Angelica enrolled in school again, and she’s striving for good grades for the first time. Cabrera has also connected Angelica with additional therapy and tutoring, and the teen is now participating in job training and mentoring programs.

After six months with CYS, progress is slow but, these days, when Angelica wraps up her meetings with Cabrera, the woman and the girl usually part from each other with a hug. “I like talking to you, Karina,” the youth now tells Cabrera.

TEACHING THE POLICE

“How many of you think the juvenile-justice system is broken?”

Deputy Chief Green always poses that question to officers whenever he introduces the CYS program at roll call or in the squad room.

Almost all hands in the room go up, he said.

“Very few cops think the current juvenile justice system is effective,” he said. “When you look at the current statistics, with a maybe 75 percent recidivism rate, the numbers really do speak for themselves.”

Still, Green understands that many cops have an initial resistance to programs that they feel might let kids off the hook for illegal behavior.

Green said that a powerful component in getting many law-enforcement officers on board is CYS’s mandated use of a restorative justice program that requires a youth to meet with the victim of his or her offenses and then to make some form of concrete restitution to that person or persons. This can include arranging financial compensation, community service or other forms of making amends.

“They have to meet face to face with their victim, and they have to find a way to make it right with that person. That’s hard,” Ellis said. “It’s a lot easier to have a judge tell you to do 20 hours of community service and you’re done. Going on informal probation–where you might get a letter from a judge telling you to bring your grades up. But hat’s not going to do anything to change behaviors or bring real accountability.”

The fact that, if a youth doesn’t complete the program with CYS, he or she will then be booked, is a factor that Green said eases the concerns of some officers.

He hailed the CYS program as an opportunity to way to exercise a “paradigm shift” at the agency, away from a “zero tolerance” approach, and toward a different type of policing.

“If we want to make sure that these kids don’t stay in the system for the next 30 years, we’ve got to try something different.”

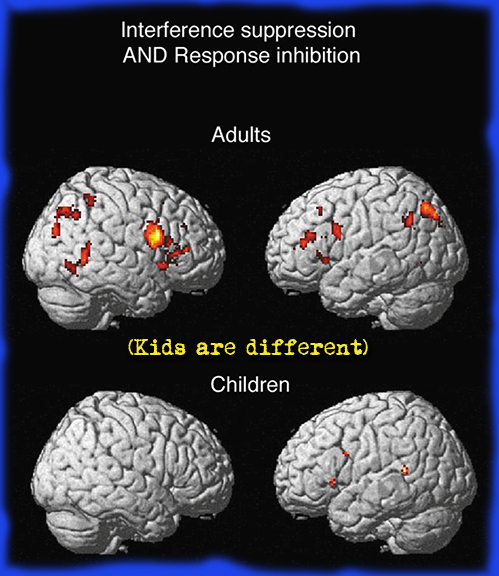

Ellis agreed and explained that another powerful tool that she has used to get both law enforcement leadership and rank-and-file on board are scans of an adolescent brain.

“The statistics [about recidivism] help open the door for credibility, and then the brain science starts opening doors to a lot of conversations about how kids are not a fixed entity and how we can change their trajectory,” she said.

Ellis pointed out that, at 15, the adolescent brain lacks the decision-making ability of a fully developed adult brain. Yet when a youth robs a store at 14, she may be seen as a “bad kid” who is beyond help or change.

“That’s the big misconception that we’re fighting,” she said. “There are structural decision-making differences in the brains of kids. All of that executive thinking doesn’t finish growing in the frontal cortex until age 25.”

WILL LA COUNTY FINALLY INVEST IN DIVERSION?

Since CYS’s juvenile diversion program began in 2012, it has continued to expand. Several additional law-enforcement agencies have come on board, including the Hawthorne Police Department, Compton School Police, Inglewood Police Department, El Segundo Police Department and Huntington Park Police Department. In December, Ellis said, CYS signed a memorandum of understanding to partner with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, specifically in the LASD’s South Los Angeles stations. And then there is the CYS program that is scheduled to open in the San Fernando Valley, with the help of Deputy Chief Green, who now heads the department’s Valley Bureau.

Yet looming over these optimistic plans for expansion is the still unresolved issue of the program’s sustainability. CYS will need $1.8 million to set up a restorative center in the Valley alone.

Moreover, the existing programs need additional case managers like Cabrera. Ellis says that the cost of a typical youth who goes through CYS’s program is $800. Kids who require the most intensive services with CYS may top out at $4000, which is still much cheaper than what it would cost to get similar services from the probation department, according to Ellis.

According to a review of the Probation Department’s budget and practices released last July, the yearly cost to the county for a youth at one of its juvenile halls was about $234,000. For a youth living in one of the county’s 14 camps, a stay there comes to a little more than $200,000 a year. The average daily population of both the camps and halls is about 1,600 youth.

Even with the money already pledged by Supervisors Kuehl and Ridley-Thomas, CYS supporters say that continuing the nonprofit’s diversion efforts will require long-term support from the county.

“It’s absurd. This is money that is sitting there dormant and is supposed to be put to work keeping kids out of the system,” Caster said. “It would be a tragedy if they drag this out, and the program has to go on hiatus. There needs to be a permanent income stream.”

For Green, CYS offers a rare opportunity for the LAPD to build toward real systems change. But without greater county leadership, he fears the moment may pass, and it will be too easy for old policing habits to return.

“Centinela Youth Services has got huge potential to build on their work, but there needs to be a commitment,” Green said.

“If funding dries up, then you’re right back where you started: hook and book.”

Jeremy Loudenback is the Child Trauma Editor for the Chronicle of Social Change

Loudenback’s story was produced in collaboration with WitnessLA’s publishing partner, The Chronicle of Social Change.