JOURNALISTS, AUTHORS, ACTIVISTS, AND RESIDENTS REMEMBER THE WATTS RIOTS

As America marks the 50th anniversary of the 1965 Watts riots this week, here are some stories we didn’t want you to miss:

Veteran TV journalist Tom Brokaw, who covered the aftermath of the Watts riots 50 years ago for NBC, says positive changes have taken place in the neighborhood, including community policing efforts, but Watts is still very much “separate and unequal.”

The LA Times has a ton of worthwhile coverage (more than twenty stories, so far) of the anniversary, including an interview with one of the few black cops in LAPD before and during the riots, quotes dug up from the LA Times’ 1965 archives, the story of Noah Purifoy’s art made from the charred wreckage of Watts, what the ’65 LA Times editorial board had to say about the six days of rioting that left 34 people dead.

Fifty years later, the 2015 editorial board takes a look at what lessons LA has (and hasn’t) learned since then. (Read more of what today’s editorial board has to say about Watts—here and here.)

The Times also compiled a list of essential literature born of the Watts riots, featuring: “A Journey Into the Mind of Watts” by Thomas Pynchon, “The New Centurions” by 1960’s LAPD officer Joseph Wambaugh, and one of our favorites at WLA, the mystery, “Little Scarlet,” by Walter Mosley.

Mosley, who was twelve years old in 1965, shares his memories of the riots in an NPR interview. Here’s a clip:

MONTAGNE: Walter Mosley went on to create the classic character Detective Easy Rawlins in a series of noir novels set in Watts. In 1965, Mosley was 12 years old and a member of an acting troupe that performed plays about civil rights, which is how he found himself in the middle of what some called an uprising.

MOSLEY: The main night of that riot, the apex of the riot, we went down to the little theater on Santa Barbara, now called Martin Luther King, to do our play. But nobody came because, you know, people were rioting. So either they were rioting or they were in their houses hiding from rioting. And we had to drive out. And driving out, we drove through the riots.

MONTAGNE: Do you remember what you saw? I mean, were you scared?

MOSLEY: I was scared, you know, because, number one, it was an interracial group, so, you know, there were a couple of white people in the car. And they were, like, on the floor. And – you know, and then you would see things – you know, people jumping out of windows, you know, like – you know, they were looting. I saw one guy just lying out on the street. I don’t know what happened to him. The police were driving by, four deep in a car with their shotguns held up, but they weren’t shooting. They were just passing through.

You could feel the rage. You know, you could feel that civilization, at that moment, was in tatters. And when I got home, my father was sitting in a chair in the living room, which he never did, drinking vodka and just staring. And I said, Dad, what’s wrong?

Go listen to the rest.

Another LA author and activist, Earl Ofari Hutchinson, in an op-ed for the Huffington Post, talks about what he saw and experienced as an 18-year-old during the riots and what has changed since 1965.

And until the 17th (the end of the riots), you can experience a unconventional live-tweet reenactment of the deadly week-long upheaval by @WattsRiots50.

BRENNAN CENTER: THE U.S. IS STILL SEEING A DOWNWARD CRIME TREND, DESPITE RECENT, WIDELY REPORTED UPTICKS IN CRIME RATES

In the midst of much media attention on crime spikes in states across the US, the Brennan Center for Justice’s Matthew Friedman says the recent crime rate upswings are still part of a longterm downward trend.

LA, NYC, Chicago, DC, and other big cities have recorded higher crime stats over the past few months. And there are many different theories as to what’s behind the changes.

LA County Sheriff Jim McDonnell blamed the higher crime rate on the passage and implementation of Prop 47—which reclassified certain low-level felonies as misdemeanors.

And during LA Mayor Eric Garcetti’s State of the City address in April, he announced a new elite metro unit would patrol crime hotspots in response to a rise in violent crime rates during the first part of 2015 in Los Angeles.

Friedman says that instead of focusing on short-term fluctuations, it’s important to take a step back, and look at the prevailing trend over a period of years, rather than months.

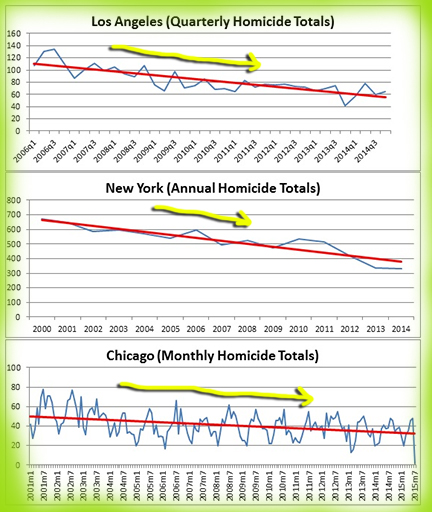

Even a cursory study of murder totals over the past two decades shows a clear downward trend in the number of murders committed in America’s three largest cities. A “trend” indicates the general direction something moves towards. The red lines in the graphs show that the long-term trend is toward fewer homicides in all three cities.

This same trend appears in most major cities across the country.

This does not mean that crime is always decreasing in these cities; in fact you can see areas of all three graphs where crime levels rapidly increase (and rapidly decrease) over short periods of time. These fluctuations are a combination of normal seasonal cycles and random events known technically as ‘noise’. Noise denotes the transient increases and decreases attributable to happen-stance or short-run shocks, but unrelated to the long-run pattern of decreasing murder levels.

Compare New York’s annual murder totals and Chicago’s monthly totals. Both exhibit the same long-term trend: a decreasing number of murders. Also note, however, that the longer time interval used to describe New York’s homicide totals generates a smoother graph that closely tracks the trend line and is almost uniformly decreasing — making it very easy to identify that city’s crime decline. On the other hand, Chicago’s graph exhibits wild fluctuations from season to season (this is known as seasonality). Monthly totals are a great way to display homicide data if you want to understand how solstice patterns impact murder rates, but it also amplifies the cyclical and noise components of Chicago’s homicide totals — making it harder to distinguish the underlying trend.

Friedman compares the crime statistics to LeBron James’ inconsistent free-throw success rate from game-to-game between January and March of this year.

…in 14 games over three months, James’ free-throw percentage increased or decreased by more than 20 percent relative to his previous outing. In multiple instances his shooting acuity fell by half from game to game. In another, it more than doubled. To assume those spikes tell us anything about James’ basketball skills would be foolish — they are just noise.

Similarly, from day to day, month to month, or year to year, crime may rise or fall due to seasonality and noise. Only by observing these changes over a sufficient period of time can we see a trend emerge. The difficulty is figuring out how many observations are necessary to cut through the noise and show us the true trend.

CONSIDERING CORONER’S PUBLIC INQUESTS AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO GRAND JURIES

Legal experts and public officials are discussing the viability of the coroner’s inquest model as an alternative to the closed-door grand jury system, as a way to promote transparency and ease tension between communities and the police after a questionable death.

Coroner’s inquests are public inquiries to determine details of a death: how and why a person was killed.

During an inquest, witnesses give testimony, but suspects don’t defend themselves, unless the coroner’s jury verdict leads local prosecutors to indict those involved.

Coroners’ inquests crop up here and there across the nation under special circumstances, but only in Montana are coroners actually required to perform an inquest after an officer-involved shooting.

The killing of 34 people during the Watts riots 50 years ago resulted in a burst of coroner’s inquests, but Los Angeles hasn’t seen an inquest in over three decades. The last coroner’s inquest in Los Angeles was held in 1981. Current LA County Medical Examiner-Coroner Mark Fajardo said he considered initiating an inquest into the death of Ezell Ford, a unarmed mentally ill man shot by LAPD officers last year, but chose not to without carefully reviewing the process.

The LA Times’ Doug Smith has more on the issue, as well as the history of the inquest in LA. Here are some clips:

At the urging of County Medical Examiner-Coroner Mark A. Fajardo, who reviewed all police shootings in his job as Riverside County coroner, the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors has asked key agency heads to rethink the review process with an eye to increasing transparency.

Fajardo, who became L.A.’s coroner in 2013, said he found it “troubling” that the office had no review procedures.

“I think the Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner should have a process that assures quality, assures efficiency and is transparent in some respect,” Fajardo said.

He said he considered calling an inquest into the Los Angeles Police Department’s fatal shooting of Ezell Ford last year, but held back because he hadn’t fully vetted the process. The county is still reviewing various options.

Some municipalities, like Clark County, NV, have successfully implemented updated versions of the inquest model.

Clark County, Nev., dropped its automatic coroner’s inquest process in 2010 after the police union successfully challenged it in court.

In its place, county commissioners set up a system that achieves some transparency at the expense of immediacy.

After every killing by police, if the district attorney finds no cause to prosecute — which has almost always been the case — the county manager convenes a hearing to examine the evidence in public. The prosecutor calls witnesses, primarily the officers who investigated the slaying. A hearing officer and ombudsman, both appointed by the county manager, can call and question witnesses in a cross-examination format, but not under oath. The officers involved in the killing do not testify.

Anyone attending the hearing can submit questions to the hearing officer or ombudsman, who is appointed to represent the public and the deceased’s family. The whole proceeding is live-streamed on the county TV station and the videos are posted on the county manager’s website.

No findings are made. “It simply concludes,” said Robert Daskas, the deputy who oversees the district attorney’s response team.

There are critics, among them the Nevada ACLU, who say the new process is toothless. But Daskas credits it for easing the tension surrounding troubling events.

“We all see the protests and the riots,” Daskas said. “I would like to think that one of the reasons we have not had issues like that in Clark County is because we provide a very transparent review of officer-involved shootings.”

MacMahon, the English economist who has studied America’s inquest tradition, finds the Clark County process an admirable compromise. He argues that it is the very toothlessness of such reviews that give them the healing power that he calls “soft adjudication,” a hearing process that is investigatory, rather than adversarial, and non-binding.

“Precisely because their verdicts do not carry binding or coercive consequences…inquests can aim more squarely than other legal proceedings at establishing the truth about a contested event,” MacMahon writes in his article.

The Watts riots news roundup was updated August 14, at 7:30p.m.