[W]hile [a prosecutor] may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland, in Berger v. United States (1935).

In the last few years there has been a lot of much-needed discussion about holding district attorneys and other prosecutors accountable for their actions.

It is heartening that much of the progress in prosecutorial reform is being made by the prosecutors themselves. Yet, there is a long way to go. And, despite all the excellent prosecutors, it appears that, for many others, winning big is still the gold standard, not seeking justice.

Matters have not been helped by the fact that district attorneys—and those who work for them—are rarely held answer for ghastly errors, or straight-up misconduct.

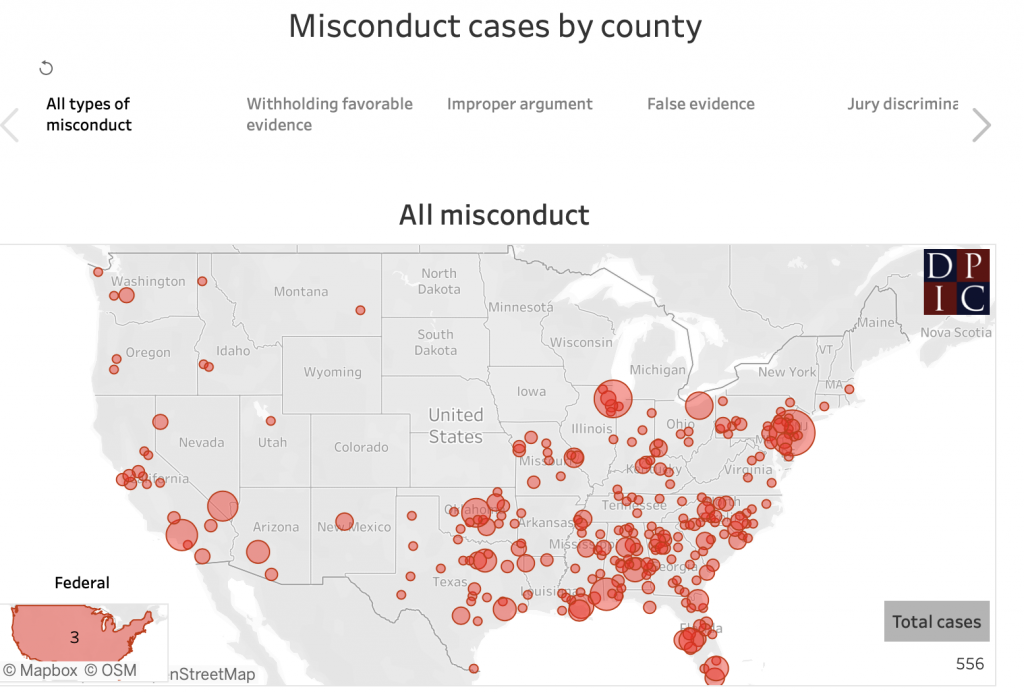

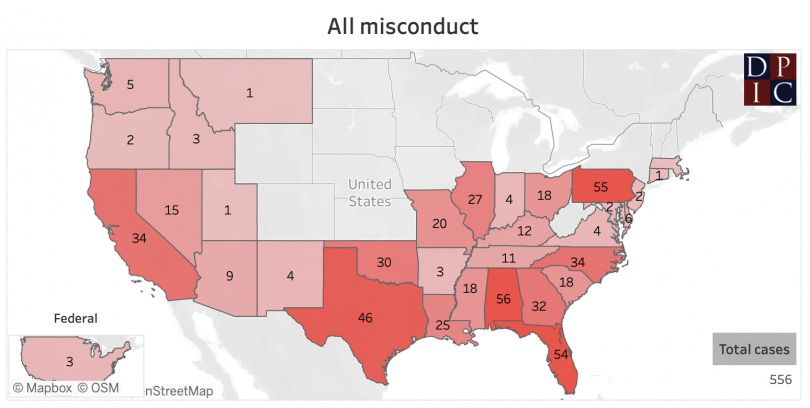

One disturbing new view of the cost of prosecutorial misconduct is illuminated by a new report released last Thursday, June 30, by the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), which has identified more than 550 instances of reversals and exonerations in death penalty cases that were based on prosecutorial misconduct.

To look at the numbers another way, this means that at least 5.6% of death sentences imposed in the U.S. since 1972—i.e. the half century after the U.S. Supreme Court struck down existing death penalty statutes—have been reversed for prosecutorial misconduct or resulted in a misconduct exoneration.

“The data on wrongful convictions has long shown that prosecutorial misconduct is a significant source of injustice in the criminal legal system,” said DPIC executive director Robert Dunham.

The DPIC’s new research, said Dunham, documents a situation that some judges have described “as an ‘epidemic’ of misconduct, is even more pervasive than we had imagined.”

Furthermore, said Dunham, the new report provides only a glimpse of the prosecutorial misconduct “that occurs in the death penalty context,”

For example, the list of instances the DPIC researchers have compiled does not include cases in which prosecutors committed misconduct “but courts denied relief on grounds of supposed immateriality or harmless error.”

Nor does the report include misconduct reversals of crimes that were charged as capital offenses, but that didn’t result in life sentences.

The DPIC report helpfully breaks its more than 550 misconduct reversals and exonerations into seven main categories of prosecutorial misconduct, with an additional catchall category of “other.” which covers types of misconduct that are less common.

The seven main categories are:

- withholding favorable evidence

- jury discrimination

- improper argument

- improper questioning

- false evidence

- improper evidence

- the presentation of evidence obtained “in violation of the right to counsel.”

The DPIC found that the most common of these seven categories of misconduct, was the withholding of potentially exculpatory evidence, in violation of the U.S. Supreme Court case, Brady v. Maryland, which the researchers said was implicated in 35 percent of the reversed convictions or sentences.

The second most common was improper argument, which was present in 33% of the reversed sentences.

And in 16% of the misconduct reversals or exonerations the researchers found that more than one category of misconduct was involved.

Unsurprisingly, according to the report, a common form of the second category of prosecutorial misconduct, “jury discrimination,” came in the form of the exclusion of people of color from juries, in violation of the U.S. Supreme Court case of Batson v. Kentucky.

This particular category, noted the researchers, was additionally problematic in that, statistically, all-white and nearly all-white juries have been found to be more conviction-prone “and more likely to impose death sentences.”

State to state and county to county

When the report looked at the matter regionally, Los Angeles County had 13 of the 550 cases of prosecutorial misconduct in death penalty exonerations, a number that was high, but not when compared to Philadelphia County, PA with 28 such cases. Cook County, Ill, also beat LA County in this painful race with 19 cases. Mobile County, AL, had one more case than LA did with 15 death penalty cases brought about by prosecutorial misconduct, which eventually resulted in exonerations.

On a state level, California had 34 death-penalty exonerations featuring prosecutorial misconduct, according to the new report, with five states scoring a higher number. (See chart above story.)

The DPIC points out, however, that the fact that some states and counties have much higher numbers than other similarly populated states and counties, when it comes to exonerations in capital cases that prominently feature prosecutorial misconduct, doesn’t mean that such scores let other regions off the hook.

According to Dunham and the DPIC researchers, the number of these cases depends on a combination of factors, including “how willing courts and other decision makers are to reverse or exonerate in cases involving prosecutorial misconduct.”

The tight-rope walk of death-row exonerations

The matter of the willingness—or lack thereof—of courts and other decision makers to pursue exonerations, is particularly sobering when considering the 121 cases on the new report’s list in which prosecutorial misconduct was discovered that eventually led to an exoneration, occurred when the wrongfully convicted person was on death-row.

In some death-row exonerations, the misconduct turned up in multiple trial proceedings, such as in the notorious case of Mississippi death-row survivor Curtis Flowers.

Race, misconduct, and exoneration

One more thing. In the DPIC’s 2021 Special Report: The Innocence Epidemic researchers found that 69% of death-row exonerations have included misconduct by some kind of official or officials. Sometimes the misconduct was committed by prosecutors, other times the misconduct was by police, or other government officials.

Unsurprisingly, the 2021 report also found that significant misconduct was “disproportionately prevalent” in death-row exonerations of defendants of color, “especially Black defendants.”

While official misconduct was also a significant factor in exonerations of white death-row survivors, said the DPIC researchers, and present in 58% of those cases, it contributed to 79% of the wrongful convictions of Black death-row exonerees and 69% of Latinx death-row exonerees.

And on a related but slightly different topic, if you’ve never listened to the podcast series, In the Dark, Season 2, about the many prosecutions of the above-mentioned Curtis Flowers, give it a try. It’s painful, but brilliantly done.

In the podcast you’ll get to know District Attorney Doug Evans the Mississippi prosecutor who tried Curtis Flowers six different times for the same crime of murder, over multiple decades in Winona, Miss., with the last of the six convictions overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court.

In November 2022, however, the longtime Mississippi prosecutor hopes to change jobs. District Attorney Doug Evans is running for District Court Circuit Judge

“In the last few years there has been a lot of much-needed discussion about holding district attorneys and other prosecutors accountable for their actions. ”

It looks like the public Is holding George Gascon accountable for his actions. He will be gone good ….

Celeste, although I didn’t have time to read your story, there are media reports stating 700,000 taxpaying citizens agree with you and have signed a petition to recall Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascon.

The denial of due process Constitutional right to fair trial occurs under each of the

seven main categories of prosecutorial misconduct.

However, the exoneration file is only the starting point for any estimation of the amount of actual wrongful convictions.

The enormity of the problem is compounded by procedural developments in the last 40 years whose impact has been completely ignored.

Federal and most state criminal sentencing procedure operates as extreme coercion forcing a wrongfully convicted and factually innocent defendant to provide a false confession of guilt.

Following conviction at trial, the defendant is subject to a penalty phase where the rules of evidence are thrown wide open and the court may be provided testimony on aggravating factors and mitigating factors for consideration in formulating the sentence.

In this phase, the court can receive highly emotional and unverifiable victim impact testimony.

This testimony usually concludes with a personal appeal for levy of the most extreme punishment available.

Finally, the convicted defendant is allowed to provide testimony for consideration in mitigating the penalty decision.

This is a defendant’s opportunity to enter highly emotional and unverifiable testimony into the record.

Although its not written in the code, over the past 40+ years it has come to be understood that judicial procedure solicits specific mitigating testimony from defendant of the category labeled as “remorse”.

This is the final chance for a defendant to counter the weight from victim impact statements.

The admission of guilt is implied by any convincing demonstration of remorse.

A defendant who refuses to relinquish a claim to innocence following the conviction is looked upon by the court as a character of the most obscene, despicable, defiant, unredeemable nature who qualifies for maximum penalty.

There is no exception here for a factually innocent defendant who wants to maintain a record of honest testimony.

To spare oneself from the worst possible outcome, to avoid a sentence of death, our contemporary justice system demands the defendant lie about his guilt, express remorse and seek forgiveness for a crime wrongfully attributed to him.

The 19 exonerations for L.A. County is too low. There are more wrongfully convicted still languishing.

A few years ago, L.A. District Attorney Jackie Lacey announced the debut of a Justice Integrity unit to review cases of possible wrongful conviction.

Lacey set the ground rules to minimize damage to the D.A.’s historical record and reputation by controlling the number of wrongful convictions brought to the surface.

For any case to qualify for a Judicial Integrity review, there must be an unbroken, sustained claim of innocence maintained by defendant.

If that requirement is still in effect at L.A. D.A., then in all fairness,

it should be rescinded.