When we look at how well or poorly a program or strategy in the criminal justice realm is working, the gold standard of assessment has traditionally been whether or not the strategy lowers recidivism rates.

Yet, in an intriguing new paper published this month, nationally regarded justice reform experts Jeffrey Butts and Vincent Schiraldi caution against falling into the “recidivism trap.”

When used as the sole measure of effectiveness, Schiraldi and Butts write, “recidivism misleads policymakers and the public…” and “focuses policy on negative rather than positive outcomes.”

Recidivism is not a comprehensive measure of success for criminal justice in general or for community corrections specifically, according to the two authors. When used to judge the effects of justice interventions on behavior, the concept of recidivism may even be harmful, “as it often reinforces the racial and class biases underlying much of the justice system.”

And that’s a big problem say Butts and Schiraldi.

Jeffrey A. Butts, Director of John Jay College’s Research & Evaluation Center/ photo courtesy of John Jay

In addition to individual behavior, recidivism is at least in part a “gauge of police activity and enforcement emphasis,” contend the two researchers.

For instance, if a city’s policing practices are more aggressive in low income, high crime minority communities, recidivism as a key measurement of the success of a program “may disadvantage communities of color” by providing skewed numbers for behaviors of those residents, when the same behavior would not produce the same numbers for residents of another neighborhood.

“Suspects who are disrespectful and contemptuous of legal authority and those who abide by the ‘code of the street,'” the authors write, citing a 2016 study, “are more likely to find themselves arrested and treated harshly by the justice system.” In this same way, “suspects willing to appear submissive and polite to authority figures, on the other hand, are more likely to be warned than arrested, more likely to be offered services rather than sanctions, and more likely to be treated in the community rather than incarcerated.” Recidivism, according to Butts and Schiraldi, cannot be accurately seen as a “sanitized measure of individual behavior.” It is also “a measure of how individuals are perceived when they come into contact with legal authorities.”

Furthermore, relying on recidivism defines the mission of community corrections “solely in law enforcement terms,” which has the effect of relieving agencies and policy makers of their responsibility for “other important outcomes that affect community health and safety such as employment, education, and housing.”

Butts and Schiraldi concede that recidivism will always be a feature of justice policy and practice. Their purpose, they say, is not to try to end the use of recidivism as a justice system measure, but to “illustrate its limits.”

They also want to convince policy makers that, in addition to taking a hard look at how we use recidivism as a measuring tool, we need to develop and to use more “suitable” measures, which will give us more accurate results—even if getting there takes a little more work.

Defining recidivism

WitnessLA’s Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (which is admittedly long in the tooth) defines a recidivist as “one who relapses,” from the French recidere, fall back.

The authors point to the far newer 2017 Miriam-Webster, which defines recidivism as the “tendency to relapse into a previous condition or mode of behavior.”

From a criminal justice perspective, when the word is looked at as a measuring tool, the definition varies. Some researchers define the measure as “any new arrest of an individual following a justice intervention.” Others measure it according to new prosecutions or subsequent convictions. And there are still other views. Yet, the bottom line for a casual reader of criminal justice research, say the authors, would likely be the assumption that “recidivism” — along with the general incidence of crime — “is a foundational metric for public safety.”

But settling for this assumption is “unwise.”

Vincent Schiraldi, Senior Research Scientist. Columbia University School of Social Work/ courtesy of Columbia University

For one thing, Schiraldi and Butts write, when used to judge the effects of justice interventions on behavior, the concept of recidivism usually fails to differentiate between other factors affecting different kinds of populations.

It is foolish, they point out, “to compare two recidivism figures without accounting for the population base.” For instance, a one-year recidivism rate among first-time probationers may be 15 percent. Yet, during the same time period, the figure for state prison inmates would often exceed 50 percent.

But, obviously, write the authors, this does not mean that probation is “three times more effective than prison at curbing recidivism.” The vastly different numbers reflect the two different populations.

By the same token, recidivism can’t be accurately used to compare two different programs, if the populations those programs serve are not comparable in terms of things like “prior record, most serious offense ever, extent of drug use, schooling, employment history, social class, and race.”

It would be unfair and all but useless, the authors write, to assess the relative effectiveness of two programs using a simple, common recidivism measure, without controlling for these myriad other factors.

And yet we do this all the time.

Okay, so what other measures should we use?

In order to best understand the alternatives to recidivism as an accurate way to assess the effectiveness of a public safety or community corrections programs, Schiraldi and Butts believe that it helps to rethink the goal of a justice intervention as “supporting desistance” rather than preventing recidivism.

In a “desistance framework,” they write, crime reduction is viewed as a process of change in which individuals learn to be law-abiding over time.

In other words, rather than using the binary framework that only sees people as either succeeding or failing with no middle ground, “desistance” recognizes the steps along the way to becoming a law abiding community member, a process that may include “occasional setbacks.”

To put it another way, recovery programs for those with drug or alcohol problems promote sobriety and emotional and social health, rather than focusing solely on not falling off the wagon. Recovery programs do so because it is broadly recognized that the path to sobriety and healing is complex and usually involves some stumbling along the way, as is the case in most other forms of behavioral change. Therefore measuring the data of failure exclusively cannot help but be a flawed model.

One misdemeanor committed by a former armed robber with multiple prior offenses would be an instance of recidivism, write Butts and Schiraldi, but it might also be “an indicator of progress toward eventual desistance.”

As with recovery from alcohol or substance abuse, the difference the authors describe is more than rhetorical. It suggests an entirely different perspective of how change actually functions.

Focusing on desistance instead of recidivism, they write, “leads justice systems to reorient their operations and their measurement of success.”

One viewpoint solely punishes failure, while the desistance framework “encourages justice agencies to promote and monitor positive outcomes.”

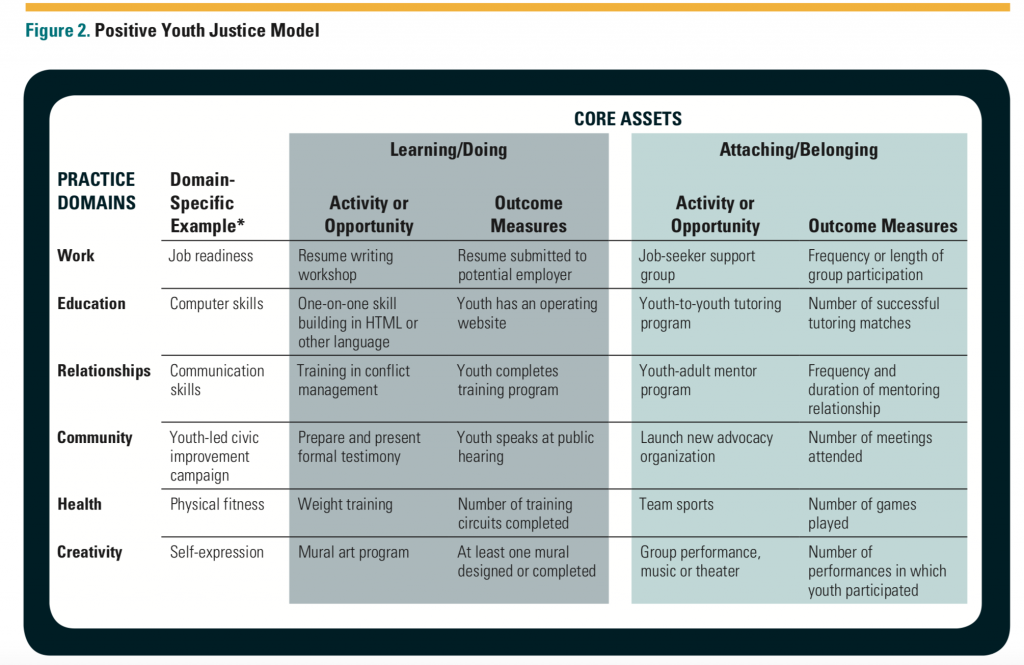

“Ideally, a youth justice system would employ multiple interventions within each of the six practice domains”/ source Butts, Bazemore, & Meroe

The metrics of change

In their paper, Butts and Schiraldi cite a recently published report by the British government, which asked the question, “What helps individuals desist from crime?” With this inquiry front and center, the British report’s authors did a comprehensive review of existing research and literature on the topic, and identified nine critical factors that they believed best answered their question:

1. Getting older and maturing

2. Family and relationships

3. Sobriety

4. Employment

5. Hope and motivation

6. Having something to give to others

7. Having a place within a social group

8. Not having a criminal identity

9. Being “believed in”

Some of these factors would be difficult or expensive to measure, Schiraldi and Butts admit. But a justice system that tracked them consistently would inevitably pursue a different intervention regime for justice-involved individuals.

Sobriety and employment are already a target of community corrections agencies, but an agency focused on desistance in general would view such issues from “an asset-based perspective rather than a deficit-based perspective.”

Asking probation officers to focus on “family and relationships” and “having a place within a social group,” they write, “would revive the social work heritage of community corrections (as opposed to its modern law enforcement orientation) and create meaningful points of intervention.”

This may sound amorphous or slightly touchy-feely but, apart from the realm of criminal justice, Butts and Schiraldi’s contentions in this paper are supported by decades of on-the-ground research into what allows certain members of populations who have undergone profound trauma to be resilient, while others have a harder time recovering. Having a place of value in a community, and feeling that one has something to offer to that community, are among the most important factors.

Measuring access to these desistance-promoting elements would, the authors say, help to redefine the role of community corrections. This would mean that, rather than focusing their time on “monitoring compliance and imposing punishments,” probation workers would naturally concentrate on supporting positive changes and achieving success.

“What you measure is what you get”

In conclusion, Butts and Schiraldi write, if community corrections programs were designed to facilitate desistance rather than simply combating recidivism, they would focus their efforts on maximizing skills, strengths, and various positive assets that in turn help to promote successful reentry, and a stable, productive life in the community.

Measuring positive outcomes, they believe, would also inspire corrections staff “to pay more attention to connecting clients with services, supports, and opportunities that facilitate desistance,” which would in turn foster more positive outcomes for the clients.

This new emphasis would—the authors concede—require more ambitious data collection and analysis, which would have to go beyond only gathering law enforcement data. “Even a sample-based approach to collecting this information would be costly,” the authors write.

Yet, the investment would help to “change the public conversation about crime, justice, and public safety.”

And while Schiraldi and Butts don’t appear to expect such changes to occur overnight, they end their paper by quoting the adage that “what you measure is what you get.”

This report by Butts and Schiraldi is one of a series of papers on community corrections that are the result of the Executive Sessions program at the Harvard Kennedy School, which brings together “individuals of independent standing who take joint responsibility for rethinking and improving society’s responses to an issue.”

Members of the Executive Session on Community Corrections includes an impressive list of justice reform involved individuals on both the right and the left from all over the nation, who came together with the aim of “developing a new paradigm for correctional policy at a historic time for criminal justice reform.”

Jeffrey A. Butts, Ph.D., is Director of the Research & Evaluation Center at John Jay College of Criminal Justice at the City University of New York.

Vincent Schiraldi, M.S.W., is a Senior Research Scientist at Columbia University School of Social Work and Co-Director of the Columbia University Justice Lab.

The inconvenient truth for social justice types is that locking up recidivist criminals actually works. This is obvious, as it resulted in record low crime rates. Of course they can’t admit it,so the result is gaslighting articles like this one. As an aside, I don’t think I’ve ever heard or read anything from anyone from John Jay college that wasn’t completely full of crap.

Maj Kong, you read? Impressive. And, its “obvious?” Why someone hasn’t recognized your genius boggles the mind, as you are obviously very smart. And, the the way you feel about those John Jay papers you claim to have read, is the way I feel reading your police reports, albeit it is a bit easier to read your reports. No doubt you would advocate locking up all blacks, as that would obviously lower the crime rate, as would locking up all Latinos. Hell, through in the Asians to lower it more. If we shot all dogs, no one would be bitten, right. I’m sure you make your Aryan brothers proud.

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Dear Maj Kong,

This paper has nothing to do with locking people up or not locking people up. It’s about what kind of metric we use to assess programs. As for the paper, although Jeffrey Butts runs a big research group at John Jay, this project that comes out of Harvard. And, Vincent Schiraldi is at Columbia. But before he began doing research there, he was the director of juvenile corrections in Washington DC and widely credited with reshaping that system for the better. Prior to that, he was commissioner of the New York City Department of Probation, and reformed that agency. Both men are in high demand to consult with agencies all over the U.S.

Just thought you’d like to know. Have a good Monday.

C.

Maj Kong, Please absorb the research and the validity concerning this article. It would be wise for you to “Be quick to listen (read) and slow to speak (respond)” . Your big mouth & response has been duly noted and properly silenced.

Celeste, I didn’t say the paper said anything about locking people up, I merely said locking up recidivist criminals works, and that social justice types don’t like it. In fact they they are so upset by this that they pay for, produce, and reprint nonsense (e.g. Mr Butts paper) in order to explain away the obvious.

OK…Takeaway…we should have separate baselines from which to measure different groups by? To put in the language CF understands…literally “black and white”, black people in poor communities should be given more latitude with respect to acts of criminal behavior, than white people in affluent neighborhoods due to inherent socio-economic differences. Interesting, also but can be interpreted as insulting to a group in a poorer socio-economic class as they are considered unable to control themselves in a civil manner, these groups have gone so far off the path of morality, civility and created a separate sub-culture and there needs to be formalized separate and unequal treatment when it comes to handling these groups.

The article makes valid points regarding a complex problem. How will change be implemented other the the California approach of decriminalization, sentence reforms and prison-realignment will be the test.

Hey CF/Reg, this is how you spell “throw”, just thought I’d give you the heads up. Celeste why do you let people post under more than one name? You know people are doing it so why not just stop it, that so hard to do? I don’t care their politics it just shouldn’t be allowed.

This is just more leftist bs and understand this is the website’s function so expect it so don’t get mad about it, just call it for what it is. All these silly rules and allowing multiple posting names, how stupid.

Thanks for another interesting article, Celeste.

Best wishes,

Richard Lanham Fremon

Maryland

Richfield, Ohio 8/12/2000

A couple of points that I believe are pertinent to the discussion.

1. Focusing on recidivism as the “gold standard” often precludes (or masks) measures that assess outcomes for which agencies or program should be accountable. For example, holding an education program responsible for criminal desistance makes it easy to say the program is ineffective when, in fact, it is doing what is supposed to, i.e. improve subjects’ reading, mathematical and other skills, getting them through GED programs, etc. More importantly, it can mask more meaningful systemic measures that more completely account for the ultimate outcome, i.e. subjects with good educational outcomes fail because the system fails to provide meaningful employment opportunities that exploit the educational achievements. In other words, programs and people can only do what they are charged to do. If they accomplish that bounded objective and the “final” result is less than we expect, perhaps we need to reevaluate the linkage between the specific program objective and the final results to identify other critical links in the causal chain.

2. Many years ago, some colleagues and I envisioned the development of a recidivism metric that combined a binary (yes/no) measure with a measure of time to failure and another measure of relative seriousness. It was our belief that the binary measure should be ameliorated/exacerbated by longer/shorter times to failure and by whether the seriousness of behavior seems to be on a downward or upward trajectory. Such a more complex measure may have a place in the discussion.

R. Douglas Kosinski

Program Evaluation Manager