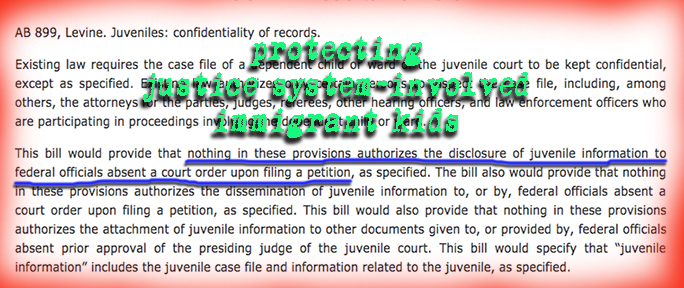

UNDOCUMENTED BOYS AND THE JUSTICE SYSTEM

A CA bill would protect juvenile justice system-involved immigrant children from being deported by banning the unauthorized disclosure of kids’ records to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement without a court order.

The bill, AB-899, authored by CA Assemblyman Marc Levine (D-San Rafael), awaits Governor Jerry Brown’s signature.

While county probation departments have been cutting back on how many undocumented kids they refer to ICE, advocates and immigration attorneys say this practice of reporting minors violates children’s civil rights, and contradicts the state juvenile justice system’s rehabilitative objectives of keeping kids in their communities, connected with their families, and acting in the best interest of children.

In Orange County, kids in juvenile hall who are suspected of being undocumented, can be interrogated by ICE agents without their parents of legal representation. The kids are not told of their right to a lawyer, phone call, or trial by judge before they are subjected to the interrogation.

Then, the children’s statements are often used against them during deportation hearings.

During deportation proceedings, kids are taken from their families and communities and sent to group homes and federal detention facilities across the nation.

Part one of four-part series by the Voice of the OC’s Yvette Cabrera about undocumented boys’ contact with the criminal justice system, tells the story of a 14-year-old referred to ICE and taken from the OC all the way to Texas, without informing his mother of his location. Here’s a clip:

One young man who is part of this generation of boys agreed to share his story, and with his mother’s consent and participation allowed a Voice of OC reporter to follow his case over nearly a three-year-period as it proceeded in immigration court. Since he is a minor in the juvenile justice system, the Voice of OC is using the pseudonym of Alex, for the minor, and Marisa for his mother to protect the minor’s privacy.

In the summer of 2012, immigration authorities entered Orange County’s juvenile hall and took Alex, then a 14-year-old, into federal custody and allowed him to make one phone call to his mother, Marisa.

The ICE agents told him he might be sent to a Texas facility, but Alex told Marisa over the phone that he knew little else about where he was headed.

She was in disbelief.

Her son had landed in juvenile hall after bringing a pocket knife to school, but she couldn’t understand how Alex ended up in the hands of immigration authorities.

She feared the worst — that Alex would be immediately deported to Mexico, where he was born.

A native of Mexico, Marisa, who is now 36, was 17 when she became pregnant with Alex. But at the time her relationship with her boyfriend had turned so violent, she almost miscarried. When Alex was nearly three-years-old, she took him and fled her physically abusive partner and crossed illegally into the United States.

She was determined to create a new life in California, but ended up falling into two other abusive relationships.

Alex witnessed his mother being abused, and experienced physical abuse at the hands of his mother’s partners as well. The consequences of his turbulent childhood would emerge early on, but Marisa never imagined when Alex began acting out in school that it would one day lead to his possible deportation.

When ICE agents placed Alex in custody in August 2012, Marisa was still undocumented, without a driver’s license and fearful that any contact with federal immigration authorities would lead to her own deportation.

“I felt awful,” she said in Spanish, pausing to catch her breath as the upsetting memory of that day washed over her. “I knew I wouldn’t be able to go see him in Texas.”

Immediately after the call from Alex, Marisa began to scour the Internet, searching for group homes that house refugee immigrant children and those in deportation proceedings. But she could not find him. She called an ICE facility in Los Angeles – only to learn that Alex was no longer there.

“Nobody would tell me where my son was,” said Marisa, wiping away tears. “It was horrible. I stayed up all night asking myself, ‘Where can he be?’”

Marisa’s struggle to find her son was the beginning of a much more difficult ordeal: Trying to keep federal immigration authorities from deporting him so that he could return home to Orange County, where he had spent the majority of his childhood.

In part two of the series, Cabrera zeros in on the debate about whether federal immigration law and policy trumps state and local law meant to protect kids and their juvenile records, and the groups that are wading into the battle. Here’s a clip:

The law, California’s Welfare and Institution Code section 827, states that unless special permission from a juvenile court is granted, only a limited and specified group of individuals from the state’s juvenile justice system is given authority to inspect a minor’s case files. Among those authorized are the district attorney, child protective agencies, or law enforcement officers who are “actively participating in criminal or juvenile proceedings involving the minor.”

Section 827 does not include ICE or any other federal immigration authorities.

The Orange County Probation Department cites the federal law, Section 1373 of Title 8 in the U.S. Code, as its legal authority to communicate with immigration authorities.

According to the law, state and local entities can’t prohibit or restrict communication with ICE, nor prohibit or restrict any government entity or official from sending information to ICE or receiving information from ICE regarding the citizenship or immigration status of an individual.

Catherine E. Stiver, Orange County Probation Department’s division director for juvenile court services, oversaw the most recent revisions to the department’s ICE referrals, including changes in 2012 that cited the federal law for the first time.

Under the authority of Section 1373, Stiver said there is no need for immigration authorities to request a special juvenile court order to grant ICE access to a juvenile’s court files or personal information.

“The [juvenile] court cannot dictate what we release and receive from ICE,” said Stiver.

Probation spokesman Edward Harrison added that the federal law supersedes state laws, including the provisions in the Welfare and Institutions Code regarding juvenile confidentiality.

“The U.S. code, like the Constitution, supersedes state code and local ordinances. That’s the law over the land,” said Harrison, who also serves as the agency’s director of communications and research.

But some legal scholars and immigration attorneys throughout California disagree that federal immigration law preempts California’s juvenile confidentiality laws. On the contrary, they say, federal law recognizes the importance of protecting the privacy of juvenile court records, including from other federal agencies.

“Neither Congress nor the Supreme Court has ever recognized any broad exception that would allow state and local agencies to breach confidentiality to share information with federal immigration authorities, particularly when such information sharing would pose a detriment to the child,” stated a 2013 report published by UC Irvine School of Law’s Immigrant Rights Clinic on this issue.

[SNIP]

Los Angeles immigration attorney Kristen Jackson of the Public Counsel pro bono law firm said she discovered in some of her Orange County cases that her clients’ immigration court files were “chock full” of confidential juvenile court documents.

In those cases, Jackson sent ICE letters warning the agency that the documents were released in violation of California law, and as result the government did not submit the documents in immigration court. The issue, she pointed out, is that the documents will remain a part of the individual’s immigration file for the rest of his or her life.

“So it may start with this, but it doesn’t end with this,” said Jackson.

SHOULD THE MEDIA SHARE GRAPHIC KILLINGS LIKE THAT OF JOURNALIST ALISON PARKER AND VIDEOGRAPHER ADAM WARD IN VIRGINIA?

On Wednesday Vester Lee Flanagan II, a one-time WDBJ-TV reporter in Roanoke, VA, shot and killed former journalist colleague Alison Parker, 24, and cameraman Adam Ward, 27, during an interview on live television. The woman Parker was interviewing, Vicki Gardner, was also shot, but underwent emergency surgery and is expected to survive.

Flanagan led police on a chase, at the end of which, he shot himself.

Flanagan, who went by the name Bryce Williams, recorded the horrific shooting from several different angles and reportedly posted the footage on Facebook. Many others, including the media, started circulating the graphic videos. But should TV stations, news sites, and other media members continue to show the disturbing footage?

NPR’s David Folkenflik has more on the issue. Here’s a clip:

Viewers of the morning show for WDBJ-TV in Roanoke, Va., actually watched the deadly shootings of reporter Alison Parker and videographer Adam Ward. And they watched it live, unexpectedly, without warning. So did the program’s anchors, who were themselves shocked, initially uncomprehending, appalled.

Others quickly grabbed that footage from WDBJ-TV and posted it online and on the air. CNN, for example, rebroadcast a portion of the station’s video, including the shootings and a fleeting glimpse of the shooter. Anchors told viewers the network would only show it once an hour. MSNBC and Fox News do not appear to have aired the actual shots. By the middle of the day, CNN said it would hold off on showing the footage again.

The decision to air or share such material has to be a conscious choice. Often it is not. So do we, as viewers, have to think hard about what we choose to consume.

The Roanoke station where Parker and Ward worked has decided not to rebroadcast it.

“We are choosing not to run the video of that right now because, frankly, we don’t need to see it again,” Jeffrey Marks, WDBJ’s station manager, said on the air Wednesday morning. Marks’ rending observations, and those of his colleagues processing the deaths in public view, admirably sought to present well-rounded pictures of the two journalists. The station and its staffers tweeted out tributes, even as they continued to report the story.

And, the NY Times’ has a thorough report on the incident. Here’s a clip:

The shooting and the horrifying images it produced marked a new chapter in the intersection of video, violence and social media.

The day began with the most mundane of early-morning interviews. Ms. Parker and Mr. Ward were working on a story for WDBJ about the 50th anniversary of Smith Mountain Lake, a reservoir tucked among farms and rolling mountains that is popular with anglers, kayakers and sunbathers. They stood on a balcony of Bridgewater Plaza, a shopping and office complex on the lakeshore, talking with Vicki Gardner, executive director of the Smith Mountain Lake Regional Chamber of Commerce.

Around 6:45 a.m., the shooting began.

The station’s own disturbing video shows Ms. Parker screaming and stumbling backward as the shots ring out and a set of jumbled images as the camera falls to the floor. Eight shots can be heard before the broadcast cut back to the stunned anchor at the station, Kimberly McBroom.

Shortly afterward, Mr. Flanagan wrote on Twitter, “I filmed the shooting see Facebook,” and a shocking 56-second video recording, which appeared to be taken by a body camera worn by the gunman, was posted to his Facebook page. It showed him waiting until the journalists were on air before raising a handgun and firing at point-blank range, ensuring that it would be seen, live or recorded, by thousands.

Both social media accounts used the name he was known by on television, Bryce Williams, and both were shut down within hours of the shooting.

Ms. Parker, 24, a reporter, and Mr. Ward, 27, a cameraman, both white, were pronounced dead at the scene. Ms. Gardner was wounded and underwent emergency surgery, but was expected to survive. Mr. Flanagan shot and killed himself hours later after being cornered by the police on a highway about 200 miles away.

LAWSUITS AGAINST LASD MEMBERS CAN MOVE FORWARD, SAYS APPEALS COURT

On Wednesday, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that three LA County Sheriff’s Department members can be held liable in two separate lawsuits brought by Francisco Carillo and Frank O’Connell whose wrongful murder convictions cost them 20 and 27 years behind bars, respectively.

Carillo is suing former deputy Craig Ditsch, for pressuring a witness to falsely identify Carillo, who was 16 at the time, as the drive-by shooter who killed Donald Sarpy.

O’Connell, who was convicted of killing Jay French in 1984, is suing former homicide detectives J.D. Smith and Gilbert Parra for allegedly withholding exculpatory evidence from the defense.

Carillo’s attorney, Ron Kaye told the LA Times that he didn’t believe any of the three LASD employees were ever disciplined.

The LA Times’ Maura Dolan has the story. Here’s a clip:

Frank O’Connell, convicted of killing Jay French in 1984, won his release in 2012 after spending 27 years behind bars. L.A. County Superior Court Judge Suzette Clover found that sheriff’s detectives had failed to disclose exonerating information to either the prosecution or the defense.

O’Connell later sued former Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department homicide detectives J.D. Smith and Gilbert Parra, alleging that they had refused to reveal evidence impeaching the statements of three eyewitnesses as well as information about a previous attempt on the victim’s life.

Francisco Carrillo Jr., in a separate lawsuit, also said the department failed to disclose information about the reliability of an eyewitness in his case. Eyewitness testimony is a leading cause of wrongful convictions.

Carrillo was convicted of killing Donald Sarpy in a 1991 drive-by shooting. Carrillo was 16 at the time and served 20 years in prison.

In his lawsuit, Carrillo charged that former Deputy Craig Ditsch knew that an eyewitness had trouble identifying Carrillo and tried to pressure the witness when he decided to recant.

L.A. County Superior Court Judge Paul A. Bacigalupo ordered Carrillo’s release in 2011 after concluding the eyewitness testimony against him was false, tainted or both.

Attorneys for the sheriff’s employees argued that the lawsuits should be dismissed because the law was unclear in 1984 and 1991 as to whether police had to disclose evidence exonerating innocence.

Members of law enforcement have immunity from lawsuits when their actions did not violate an established law.

The 9th Circuit, citing Brady vs. Maryland, the 1963 Supreme Court decision that required disclosure of exculpatory evidence, said the authorities should have known of the requirement.

SAN BERNARDINO DA’S OFFICER SWEARS IN TWO DOGS TO COMFORT VICTIMIZED KIDS TAKING THE WITNESS STAND

The San Bernardino District Attorney’s Office has sworn in its first two K-9s as part of the Special Victims Unit. The two black Labradors, Lupe and Dozer, are specifically trained to comfort kids who have witnessed or been victims of violence while they give testimony or take the witness stand.

The San Bernardino Press-Enterprise’s Gail Wesson has the story. Here’s a clip:

With a paw atop a state Penal Code book and a black, hairy chin on another copy, the first two K-9s were sworn in and received their star badges as members of San Bernardino County District Attorney Mike Ramos’ Special Victims Unit in a Friday ceremony.

The four-legged so-called facility dogs will enhance his office’s ability to “see justice for the most vulnerable victims, our children,” Ramos said during the event where K-9s, Dozer and Lupe, mostly sprawled out comfortably on the floor, while keeping an eye on the cameras and their victim advocate handlers.

More than two years in development, the district attorney’s office is partnering with nonprofit New Mexico-based Assistance Dogs of the West, which supplied K-9s and handler training, and Washington state-based Courthouse Dogs Foundation for educating the legal community.

[SNIP]

They will be called upon to help in interview and courtroom testimony situations, primarily with children but are available for adults too. Ramos said of child victims, “Some of them have suffered tremendous physical abuse, some of them tremendous sexual abuse and some have lost their lives.” The aim is to help witnesses be comfortable as they testify in order to get cases prosecuted in court.

“Our main goal is to greatly reduce the understandable fears that a child has about entering the courtroom,” Ramos said in a written statement.