In 2013, then-California Governor Jerry Brown signed SB 260, a law that gave a second chance at parole to kids who committed murder before the age of 18 and were sentenced to life-without-parole.

A new study published in the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review examining California parole hearings post-SB 260 reveals that race and wealth significantly factor into parole decision outcomes among juvenile lifer applicants.

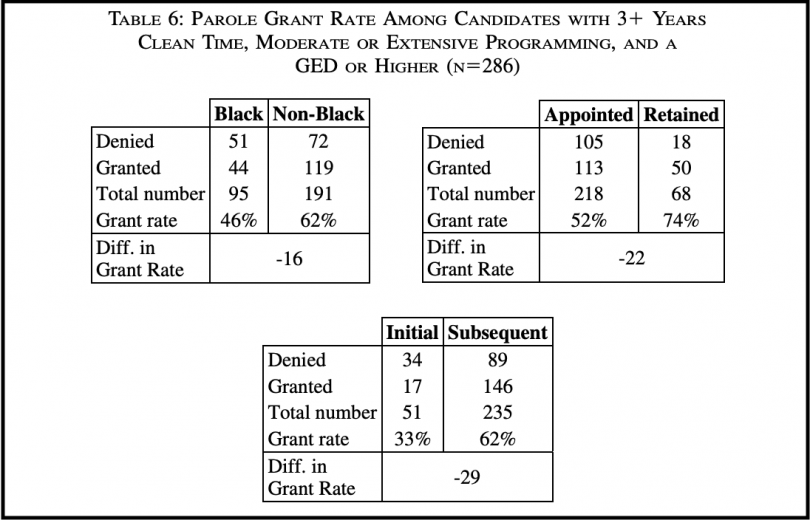

The study’s author, Dr. Kristen Bell, a professor at the University of Oregon School of Law, analyzed the transcripts of 465 parole hearings occurring during the first 18 months after the implementation of SB 260, on January 1, 2014. The transcripts showed that people who did not participate in rehabilitative programs and who had recent disciplinary actions on their records were uniformly unlikely to be granted parole. Disparities appeared, however, when the professor looked at parole hearing results for people who showed signs of successful rehabilitation.

“Among parole candidates who had engaged in rehabilitation programs and did not have recent misconduct, decisions were inconsistent,” Bell said. “The odds of being granted parole were significantly influenced by factors like race, having a private attorney and opposition by the victim’s family members.”

Bell found that black candidates were 2.7 times less likely to be granted parole than their white counterparts.

Additionally, people who hired private attorneys to represent them were 3.4 times more likely to receive parole than those who could not afford a private attorney.

State-appointed forensic psychologists whose job it is to assess individuals before parole hearings were more likely to give higher risk scores to black parole candidates than their white counterparts, according to the report.

“This study reveals that black and poor people, who were already more likely to get life sentences as children, will also be considered too dangerous to release 20 years later because they’re still black and poor,” said Keith Wattley, executive director of the nonprofit UnCommon Law in Oakland.

Of those juvenile lifers who were released during the 18-month period, none had returned to prison as of 2017.

The report found wide differences in the number of years that juvenile lifers convicted of similar crimes spent behind bars before a parole board deemed them worthy of release. One person sentenced to prison for a non-homicide crime committed as a teenager served 35 years behind bars before being released. Of two teens sentenced prison for the same crime — first-degree murder — Bell found that one spent 19 years in prison before being paroled, while the other served 43 years in prison.

“In this sense, the parole board has more control over the actual time a person spends in prison than the sentencing judge or jury,” Bell said.

While Bell praised California for having progressive parole laws, her report calls for expanded judicial oversight of the parole hearings, as well as increased public scrutiny and more objective criteria for parole decisions to reduce disparities in a system that, in practice, can be “arbitrary and capricious.”

Correlation does not equal causation. Each person is an individual with unique circumstances. You focus on one factor only – race. That’s a liberal for you.