For the young people in Los Angeles County’s 12 juvenile camps, 3 juvenile halls, and one juvenile placement center, there are three ways to respond actively to mistreatment at the hands of staff or another kid: File a “grievance” form. Tell a trusted adult and hope he or she goes to bat for you. Make a call to the Ombudsman’s helpline. But what happens when a kid desperately needs help and all of those methods fail?

Nobody listened: Michelle’s story

From November 2014 to July 2015, a young woman whom we’ll call Michelle, was detained at Camp Scudder, a county juvenile facility for girls in Santa Clarita. There, according to a civil lawsuit filed in federal court on July 14, 2017, Michelle was on the receiving end of unwanted and increasingly invasive attention from Deputy Probation Officer Oscar Calderon, Jr. which allegedly culminated in around 10 instances of sexual assault. She was 17 years old at the time of some of the alleged sexual assaults, 18 during the later assaults.

While the lawsuit is ongoing, Michelle’s story directed a harsh spotlight on the shortcomings of the system currently in place in Los Angeles County for youth to file grievances. But across the U.S., a list of jurisdictions have implemented grievance systems that seem to be working, and LA County may soon benefit from those models with its participation in a Georgetown University project, which began in December 2017.

In the amended complaint filed on Michelle’s behalf by her attorneys Justin Sterling and Erin Darling on September 6, Michelle described being discouraged from reporting any kind of grievance. “Snitches get stitches,” Michelle said she and other probationers were told by staff and officers. “You don’t want to get a snitch jacket.”

Calderon also reportedly prevented Michelle from telling her family over the phone about the escalating abuse…

Calderon was reportedly more direct. “I can do what I want,” Michelle said he told her, and that he would “fuck up” her court reports if she did not submit to him. This was not an empty threat. Because Calderon was the officer directly in charge of Michelle’s supervision for the duration of her time at Scudder, his assessments could have had a direct bearing on her release date, as well as her quality of life at the camp.

Calderon also reportedly prevented Michelle from telling her family over the phone about the escalating abuse because the deputy probation officer made sure to be physically present when she called home. She described how he sat beside her during her allotted phone time, and during some calls would “scissor” his legs with hers, touching her fingers or rubbing her legs.

At first, Michelle persisted in her efforts to call attention to the situation, despite the pressure to remain quiet. These efforts included a written plea to her godfather, who reportedly spoke to Calderon’s direct supervisor on the girl’s behalf. The supervisor assured Michelle’s godfather that she trusted Calderon “100%” and, according the the complaint, she did not investigate further.

Michelle then confided in her therapist at the camp, who also failed to act to prevent further abuse. Soon after telling her therapist, Michelle alleged, Calderon pulled her out of class and confronted her, asking, “What did you tell [the therapist]?!” From this exchange, Michelle determined that Calderon had somehow learned about her supposedly confidential disclosure, and that help was not forthcoming.

“Plaintiff desperately wanted to tell someone about Officer Calderon’s treatment of her but figured that if she could not trust her therapist then she could not trust anyone at Camp Scudder,” states the complaint. “As a result, Plaintiff gave up trying to resist Officer Calderon.”

After the incident with the therapist, Michelle’s bind was two-pronged, said her attorney, Justin Sterling.

For one thing, “the one causing the abuse was in charge of her court reports,” Sterling said. “So here we had a situation where if she reports him, it compromises and puts in jeopardy her potential release.”

Second, “we have family members on the outside making these complaints to the supervisors above Calderon, who turned a blind eye” to Michelle and her godfather’s pleas.

Problems with the grievance system

No one in the probation department is permitted to talk publicly about Michelle’s reported experiences due to the ongoing litigation. Nevertheless, the case’s troubling allegations cast a shadow over discussions about the grievance system used by the county’s juvenile facilities, and what reforms that system might require.

Last Thursday, January 11, such a discussion took place when probation higher ups made a presentation on the topic to members of the Los Angeles County Probation Commission, in response to the commissioners’ written concerns.

…the case casts a shadow over discussions about the grievance system

In the course of probation’s presentation, Luis Dominguez, Acting Deputy Director for the department’s Detention Services Bureau, told the commissioners that upon arrival at a juvenile camp or hall, a youth is supposed to be informed during an orientation session that he or she has the right to file grievances about any concerns or complaints.

The kid can do this by filling out a grievance form, which Dominguez said are located throughout living units and dormitories of every facility. Once a form is filled out, the youth can hand it to a probation staff member, a therapist, teacher, or other any other person in authority whom he or she trusts. Or the kid may deposit the form in a locked “grievance box.”

Each site has one designated grievance officer who is the only person with a key to the grievance box. According to Dominguez, grievance officers are expected to pull forms from every box in a given facility at least once a day, and then to resolve each grievance by the end of the shift.

“But that doesn’t always occur,” Dominguez admitted. “That is one of the things we need to improve.”

If the grievance officer cannot resolve the matter in the prescribed time, or if the boy or girl who filed the complaint chooses to appeal the resolution, the grievance may go up the chain of command from the Supervising Deputy Probation Officer to the Division Director to the facility’s Superintendent. Of the 335 grievances that were received for the final quarter of 2017, Dominguez said, 82 per cent were resolved at the supervisor level.

…a pervasive fear of “getting in trouble” for filing a complaint

But Probation Commissioner Jo Kaplan, who is also the co-founder of the Children’s Law Center of California, described seeing a messier process during her visits to camps and halls.

“Every kid I’ve ever talked to, in any hall,” Kaplan said, “whenever I’m talking to them, I always ask about the grievance procedure. I’ve never heard of a kid who’s been satisfied with it.”

Kaplan described what she called a pervasive fear of “getting in trouble” for filing a complaint. Those who tried to file grievances despite their fear, she said, were often unable to do so. In many instances, the grievance boxes were not placed where they were clearly visible, or there were no blank grievance forms available.

“We had requested at one point that you put a big sign above the lockboxes that says ‘Grievance Procedures’ in big writing, ‘Anything filed here will be kept confidential,’” Kaplan told Dominguez at the January 11 meeting. Thus far, she said, the request had not been granted.

…I’ve seen probation officers intercept the person who’s going to get a form

Fellow probation commissioner and retired LA Superior Court Judge, Jan Levine, added her observation that if the grievance boxes and forms are available and displayed prominently in facilities, “Everybody in the unit watches when someone walks over and pulls a form. And I’ve seen probation officers intercept the person who’s going to get a form to say, ‘You don’t want to do that.’”

According to Michelle’s attorney, Justin Sterling, his client didn’t use the complaint box “because she was scared of retaliation,” due to the lack of privacy available when retrieving, filling out, or depositing a form, that Levine and Kaplan described.

And because other probation staff were aware of Calderon’s conduct, according to Sterling, “logic would follow that placing a complaint in a drop box alleging ongoing sexual molestation would…be futile under the circumstances.”

Probation Commissioner Jacqueline Caster, a longtime child advocate who is also the founder of the Everychild Foundation, pointed out that the parents need to have their own system for reporting abuse. “I’ve asked the staff at some of the facilities what the parents do, and they said, ‘Oh, they can call us.’ But without a formal avenue for the parents’ complaints,” she said, we’ve seen what can happen.

But “nobody would ever answer. I think once I got a return call…”

Caster said that on multiple occasions she called the Probation Department Ombudsman’s hotline, a non-emergency resource for juveniles to report grievances, to check its functionality. But “nobody would ever answer. I think once I got a return call,” she said.

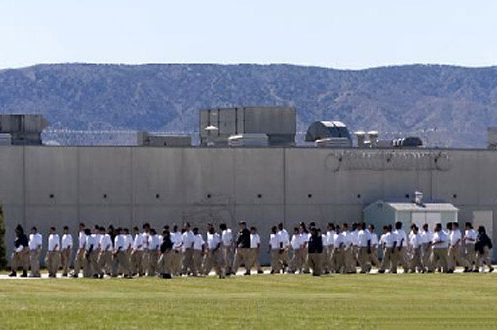

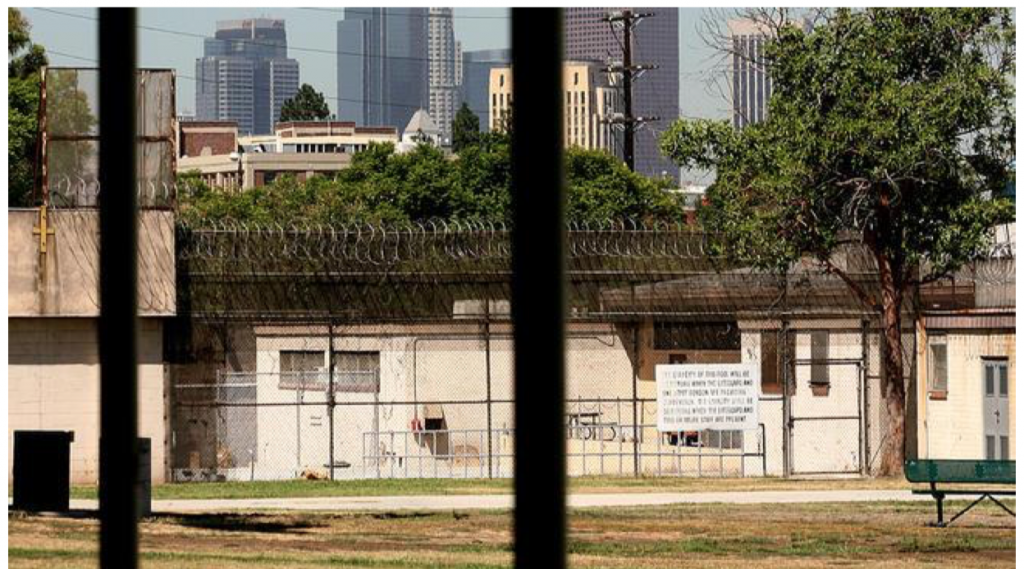

Challenger Memorial Youth Center, Lancaster, Courtesy of former Los Angeles County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky

Probation Commission records show that when Caster raised the hotline issue with Probation Department Ombudsman Jessica Gama at a commission meeting two years ago, Gama told the commission that her office was short staffed and that she would “need to provide justification for additional staff.”

Caster also told of a visit she and another commissioner made to Central Juvenile Hall. In the course of their visit, the two commissioners were given a stack of grievances. The kids’ names were supposed to be blacked out on the grievance forms “for privacy purposes,” Caster said. “But they weren’t redacted very well. You could still see every name.”

One of the most important elements of any grievance system, Caster noted, “is for the kid to feel safe.” And such sloppily redacted forms did not exactly promote a feeling of safety.

Independent monitoring

Patricia Soung, Director of Youth Justice Policy at the Children’s Defense Fund–California, said she sees a strong need for reform of what she called probation’s “opaque” grievance process. Soung described the difficulties she encountered when she attempted to help various clients get their complaints heard.

“Even a diligent attorney may have a hard time helping their client navigate the grievance process, or protecting their client from the potential backlash of complaining.”

Jason Szanyi, the deputy director of the Center for Children’s Law and Policy (CCLP), a DC-based public interest law organization that works to reform juvenile justice, is a strong proponent of independent monitoring for juvenile facilities, which he said is now considered “best practice” when it comes to ensuring kids’ safety inside such facilities.

To reinforce his point, Szanyi pointed to the 2003 Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), which stipulates that kids inside juvenile lockups should have access to “an independent, outside reporting mechanism where they can report sexual abuse” anonymously and without retaliation from abusers. This is best practice for non-PREA facilities as well.

This “independent monitoring entity” Szanyi said, must have “the authority, resources, and mandate to investigate problems that have been reported.” An outside independent monitoring entity must also be able to perform regular, routine checks “to detect and remedy concerns before they escalate into systemic problems.”

“There’s no substitute for having outside eyes and ears in a facility,” Szanyi said. “And I think it pays big dividends when folks make that investment, but unfortunately we don’t see that in many places around the country.”

…what recourse is there if a supervisor at the facility was told of the alleged abuse, and neglected to stop it?

Part of the problem, according to Szanyi, is getting state and county authorities to prioritize an independent system. Juvenile facilities that aren’t, say, at risk of losing federal funding over PREA have no financial incentive to comply with the PREA requirement, he said. That includes LA County juvenile camps and halls.

Furthermore, even those facilities that have implemented the kind of independent monitoring system that Szanyi and the Center for Children’s Law and Policy considers best practice, the issue of how to protect juveniles who report abuse from retaliation by staff—or even other juveniles—remains a tricky one.

“It’s on the facility to monitor for that and make sure it doesn’t occur,” he said. And such monitoring is a long-term endeavor and must remain in place for the duration of, and after, a rigorous and neutral investigation.

Failure to institute such rigorous safeguards puts youth like Michelle in an impossible spot. If it’s the facility’s responsibility to protect juveniles from retaliation against reporting abuse, what recourse is there if a supervisor at the facility was told of the alleged abuse, and neglected to stop it?

A window of opportunity

According to Chief Deputy Probation Officer Sheila Mitchell, the agency’s second in command and the person in charge of juvenile operations, the department has begun examining its grievance system to see what reforms are needed.

Mitchell said that they expect the process to be aided by the fact that the department was recently awarded an 18-month grant to become part of Georgetown University’s Youth in Custody Practice Model (YICPM), a program that, as probation department spokesperson Adam Wolfson put it, “will take a deep dive into our current policies and practices.”

At last Thursday’s probation commission meeting, Mitchell talked about a recent conference call with Shay Bilchik, the founder and director of Georgetown’s Center for Juvenile Justice Reform, and others who are part of the 18-month program. “Part of what they’re helping us with,” she said, “is looking at the grievance process in terms of what’s best practices across the country. So we’re going to definitely learn from that and implement what we learn.”

…That way someone doesn’t have “a big red flag on them…”

Meanwhile, Mitchell and others said the department is considering the idea of replacing the paper grievance form system with a new system that employs iPads.

One of the advantages of the iPads, according to Ombudsman Gama, is the fact that the tablets could be used for several purposes in addition to filing grievances. When asking to use an iPad, she said, probationers could say they were “checking court dates, or the terms of their probation, and then just do whatever else they needed to do.” Furthermore, she said, the grievance could be appropriately categorized, then be instantly “shot to whoever is supposed to deal with it.”

That way someone doesn’t have “a big red flag on them when they walk over to the iPad,” agreed Levine.

So what are other jurisdictions doing?

According to a fact sheet on the topic compiled by CCLP, the Office for Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, which operates under the U.S. Department of Justice, has identified five features that effective independent monitoring systems share:

1. A system must be fully independent from the agency running juvenile facilities.

2. It must have the legal authority to investigate complaints.

3. It must be granted unrestricted access to places, people, and records.

4. The system must have adequate funding and resources to conduct investigations.

5. It must be staffed with competent, expert individuals.

…if the culture isn’t set up to ensure that children are safe, all the policies and laws in the world aren’t going to help

A handful of jurisdictions around the U.S. have created independent monitoring structures which appear, more or less, to comply with the OJDP’s list above.

Texas, for example, established the Office of the Independent Ombudsman, after a national scandal erupted following allegations that thousands of kids had been physically and/or sexually abused in the facilities run by the Texas Youth Commission (TYC). The resulting ombudsman’s office investigates complaints, inspects facilities, reviews and proposes changes to policies and procedures, and issues regular reports on the office’s activities

A few other states and jurisdictions like Maryland, New Jersey, Kentucky, Connecticut, and Washington, D.C., also have similar independent monitoring systems.

Yet, one can “have the laws and the policies that say all the right things, but if the culture isn’t set up to ensure that children are safe [from retaliation], then all the policies and laws in the world aren’t going to help,” cautioned Connecticut’s Mickey Kramer, who is the second in command at the state’s Office of the Child Advocate.

In order to create the necessary safe culture in a juvenile facility, said Kramer, the facility’s leadership must communicate clearly “what the mission of the facility is,” and make sure staff roles and responsibilities are defined regarding the reporting of abuse, along with having “safe places” for kids to report violations. Then facility leadership must have a plan “to ensure that the child is safeguarded” both during and after an investigation, “whether or not the abuse was substantiated.”

Looking ahead for LA County

While many of the needed reforms to the grievance system appear to be in the earliest stages at best, LA County probation may already have a partial model for the kind of cultural reform that Connecticut’s Mickey Kramer, along with most juvenile advocates, point to as essential.

Dan Seaver, another member of the probation commission, who also runs the non-profit youth job training program ManifestWorks, pointed out a positive example he observed at a recent visit to Campus Kilpatrick in Malibu.

…it doesn’t have to be an adversarial relationship

Kilpatrick is the $58 million youth facility that opened in early July, and was designed to emphasize, as its planners described it, “a culture of care rather than a culture of control.”

“When I was at Kilpatrick a couple weeks ago,” Seaver said, “the staff knew what kids were worried about and actually were preemptively addressing those things,” circumventing the grievance system altogether.

Acting Deputy Chief Dave Mitchell agreed. “It’s a philosophy,” he said. “You should be able to work with that kid and hear his grievance out, and it doesn’t have to be an adversarial relationship,” he said. “And I think that’s the direction we need to go in.”

At this point, however, Kilpatrick staff are unique group within the department as they were carefully selected for their slots at the new model facility. They were also required to go through lengthy training in the philosophy of therapeutic, research-guided, “trauma-informed” care that the new facility espouses. Probation intends to put all of its staff members working at juvenile facilities through an equally rigorous process. But that is still in the future.

Thus, although the Kilpatrick model may be a significant step in the right direction, youth advocates like Patricia Soung believe that an external monitoring system is still necessary to protect kids in the county’s care, especially considering alleged incidents of assaults of youth by staff that were reported as recently as last year.

…a sense of urgency around the discussion of grievance system reform

“An entity monitoring itself has long failed young people,” Soung pointed out. “It’s long overdue for young people to be able to shed light on what’s happening in these institutions.”

And then there is Michelle’s case, the alleged mishandling of which has triggered a sense of urgency around the discussion of grievance system reform.

In the meantime, former Los Angeles County Probation Officer Oscar David Calderon was arrested in January 2017, and charged with two counts of lewd and lascivious acts upon a child, and four counts of assault by a peace officer. Prosecutors stated that Calderon’s victims ranged in age from 15 to 18 and that the abusive events began in 2014. Michelle was one of those alleged four victims.

Calderon took a plea deal which resulted in his charges being reduced to two felony counts of assault under the color of authority, for sexually assaulting two girls at Scudder, and making inappropriate overtures to other girls. On September 20, 2017, he was sentenced to one year in LA County Jail, and was not required to register as a sex offender.

He began his jail term on October 23.

On November 14, 2017, Calderon was released from the LA County jail system after serving less than one month of his sentence.

The top image is a photo of girls at Camp Scudder, located in Santa Clarita, courtesy of the Los Angeles County Office of Education

What a shame. This website continues to run one spurious hit piece after another designed to cast Probation in the worst possible light. Meanwhile, thousands of dedicated officers continue to serve the community and it’s children in the spirit of the department’s core value: Integrity, doing the right thing for the right reason, all the time. Maybe one of you should put on the uniform and walk a week in our shoes. You might actually come to understand the challenges and rewards of working with detained youth.

I have walked the camps and you are right about it being hard but it’s what you signed up to do. You knew you were going to work with the most troubled youth in our city. Although it is hard you guys don’t have the right to emotionally and physically attack children, yes children because that’s what they are. I have heard probation tell kids “you know why your here because you momma don’t want you, you are a loser, you are my Bitch!” And when kids do report they are treated as outcast and places in the middle of the dorms to be ridiculed and talked about for a code about “snitches” that probation is the number one violator of because they “snitch “ everything to each other and the court. It’s is tragic that a department rewards people on investigations for abuse and allows theses vulnerable youth to be te-traumatized in a place where they should feel safe. A place they should be able to reach out for help. For those few probation officers that do they job they also fail ……because they watch as their peers do the abuse and won’t teport for fear of being retaliated by their own. Don’t play the victim……,the only victims here are those poor kids who deserve a better probation system.

I have been to these camps 20 years ago. I went every from Holton, CYMC, Munz, Mendenhall, Miller, Rockey etc… They tortured us and laughed while doing it. They would make us P.T. on hot blazing asphalt where our skins would burn off. Then if we didnt do it without making a noise, we would have to do it again and again. Daily nurse visits was normal. Bee stings from having us bear crawl through bee invested fields . I got over 10 bee stings just in 4 months there only to be refiled on after complaining and filing a grievance. This was 20 years ago. The FBI contacted me but I was too scared to say anything after a church volunteer reported the staff for beating a kid in another room for talking out of turn. The DPO II grabbed the kid, punched him and threw him into a room and we heard him getting beat up. The kid came out with a busted face. The church volunteer reported him . But it was a daily thing in these camps. Don’t even let me mention CYA. The staff there was even more sinister on another level.