USING THE ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES QUESTIONNAIRE AS A SCREENING TOOL IN NON-MEDICAL SETTINGS IS…COMPLICATED

The 1997 Adverse Childhood Experiences study, by Vincent Felitti and Robert Anda, examined the long-term health effects trauma (ACEs)—like abuse, neglect, and divorce—have on kids.

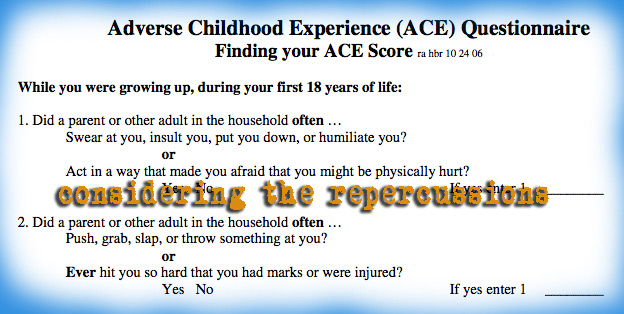

The study includes an ACEs screening questionnaire, which has become the benchmark for measuring childhood trauma. The quiz produces an ACEs score based upon how many times a person answers “yes” to the ten questions.

As the use of the ACEs test spreads from its original pediatrics setting, to schools and the juvenile justice system, some say unintended complications will undoubtedly arise.

Major training is required before an ACEs screening system can be implemented, according to experts. And schools and juvenile facilities have to be careful about what questions they ask kids because of mandatory reporting laws. Problems can arise if a child answers “yes” to the abuse-related questions, for instance, and the test administrator isn’t trained to do further appropriate questioning, but follows the mandatory reporting laws requiring the involvement of child protective services. This would likely result in the unnecessary splitting up of families if there has been a bad experience or bad conditions in the home, but the family is otherwise loving and reasonably stable.

Some of the questions can be tweaked and posed to parents, however, to get more of an overview of a child’s wellbeing while staying away from the questions that trigger mandatory reporting.

The Chronicle of Social Change’s Jeremy Loudenback has more on the issue. Here’s a clip:

“Before you ask these [ACEs] questions, you have to have a plan of action when the answer is yes,” said Blodgett. “Screening for trauma is more dicey where you get into education settings, where there’s a big conversation around this right now.”

“Most schools don’t have the capacity to figure out how to respond if there are identified ACEs,” he said. “These systems weren’t designed as identification and treatment systems. That’s when issues about potentially increased reporting become much more serious.”

For Robert Anda, a co-author of the influential 1997 ACEs study, the ACEs questionnaire is more about taking a public health approach than a tool for mandatory reporting. In screening parents, he suggests that other measures could be developed to measure risk of maltreatment without compelling pediatricians to turn to child protective services.

“ACEs can be measured safely in parents to give you an index of what may be a risk for the parents and the whole family and the child,” said Anda in an interview The Chronicle of Social Change at the One Child, Many Hands conference earlier this year at the University of Pennsylvania. “You can get other indirect measures that aren’t going to [lead to] mandatory reporting, including, I think, measuring some of the developmental functions as a proxy and stay away from the mandatory reporting.”

“We have to dig deeper and say ‘what’s going on,’ before making a decision about adjudication.”

The Center for Youth Wellness has spearheaded the use of ACEs screening tools in its pediatric clinic in the Bayview Hunters Point neighborhood of San Francisco. The California Department of Justice has looked toward the center as a model in creating its statewide trauma screening efforts, according to staff in the office of California Attorney General Harris.

The center uses the 10 questions from the original ACEs study, but has also added seven more factors that contribute to toxic stress for the low-income population served by the clinic, including homelessness, involvement in the foster care system, community violence and discrimination, among others.

But the Center for Youth Wellness’s Cecilia Chen cautions that the tool that the center uses is only designed for a specific context.

“Our screening tool is designed to be used by pediatric health care professionals,” said Chen, interim director of policy at the center. “We don’t advocate for its use in the juvenile justice and education systems. Tools don’t always translate across different sectors, and we really don’t know what the unintended consequences would be in other settings.”

Since the center has been using the ACEs tool, it has not seen an increase of children reported to child protective services, Chen said. But even in a pediatric setting, she says, training is necessary to administer ACEs and not jump to conclusions after reviewing the results.

SALINAS HIGH’S DISCIPLINE TURNAROUND THROUGH THE POSITIVE BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS AND SUPPORTS MODEL

By replacing harsh school discipline with the Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) program, the number of suspensions at Salinas High School has dropped by 70% in just two years.

Salinas High has used money allocated for disadvantaged kids to hire a full-time intervention specialist to run the PBIS program, which teaches expectations for behavior to kids just like a regular school subject.

PBIS has been such a huge success at the school that Juan Govea, a Salinas biology teacher, traveled to the White House to talk about its implementation and results at a round table discussion on school discipline.

The Californian’s Roberto Robledo has the story of Salinas’ High’s turnaround and ongoing success. Here’s a clip:

Govea was invited to the roundtable based on a previous fellowship he received and the contacts he’d made. He was not an official representative of the Salinas Union High School District. He made the trip to share the huge steps Salinas High is making in student discipline.

“They asked me to take part so they could get a teacher’s perspective. Everybody else there was an administrator or some other capacity at a school district,” Govea said Thursday in an interview.

To subsequent applause, he told the gathering that in the two years since a new behavior program was installed, Salinas High has cut its suspension rate by a whopping 70 percent.

“It’s significant when you know that the kids being suspended — typically English Learners, male, minorities — need as much school time as possible. So when they’re losing it to suspension that puts them at an even greater disadvantage,” he said.

“That 70 percent is now getting a more positive based reinforcement. It allows us to then focus on that 30 percent that is a little bit tougher.”

The Salinas district has adopted the Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports program, which reinforces the rules of behavior and the importance of following them.

“As teachers we identify the kids who need intervention. Brief class lessons during the day reinforce the rules — why tardiness is bad, why not following the dress code is bad,” Govea said.

PBIS succeeds at Salinas High with an intervention specialist working full-time to manage the program, and who gathers a team with teachers, staff, vice principal, counselors. It’s a huge undertaking, Govea said. But the school wisely used funding through the new Local Control Funding Formula to create the full-time focus on PBIS.

One of the positive outcomes Govea has seen is “showing assistant principals how harmful suspensions are for students.” Rather than using suspensions as a first course of action, “how do we address it without putting a shackle on their leg?”

A VERY RARE CALIFORNIA GRAY WOLF SIGHTING

A lone gray wolf appears to be moving through Siskiyou County, says the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. (Note: this is not the beloved OR-7 who made news as the first wolf in California since 1924 when he crossed the border from Oregon four years ago.)

The LA Times’ Julie Cart has the story. Here’s a clip:

Officials said that earlier this summer they began receiving reports of sightings of a large, dark-furred animal. Wildlife authorities set up trail cameras in an effort to catch a glimpse of the animal.

In early May, images from those cameras showed a large, dark, single animal.

In June, a state biologist found tracks believed to be that of a wolf. Cameras placed at that location yielded images of a ‘large, dark-colored canid’ on July 24.