Over the last 20 years, youth violence dropped precipitously (and unexpectedly) in California.

Law enforcement arrested minors 22,601 times for violent crimes in 1994. That arrest rate dropped 68 percent, to 7,291 arrests two decades later, in 2017.

In addition, a collective turning away from harshly punitive incarceration for kids, and a movement toward community-based diversion and services, have helped keep kids out of juvenile lockups. (But not all kids—racial disparities in the juvenile justice system have become increasingly worse.)

Thus, many once-overstuffed juvenile halls and camps in California are now operating at a fraction of capacity.

In 39 of the 43 counties that have juvenile lockups, the facilities are not even half full, according to an SF Chronicle investigative series called “Vanishing Violence.”

At the same time, the cost to lock up youth has soared in some counties, to as much as $500,000 annually for each kid, the SF Chron found. In Alameda County, in 2011, it cost $157,000 to lock up each juvenile for a year. By 2018, that number had jumped to $493,000. In Santa Clara, the 2011 rate–$187,000–more than tripled by 2018, hitting $514,000 per youth. Nevada County now spends $530,000 annually to lock up each kid.

In comparison, the state spends $11,500 per child, per year for K-12 schooling.

Local leaders in a number of counties have closed empty juvenile facilities, and adopted innovative alternatives to traditional detention, yet budgets have not changed to reflect the fact that fewer locked up youth should mean a considerable reduction in juvenile probation spending.

After all, community-based interventions and care cost a fraction of what states and local governments spend to incarcerate youth.

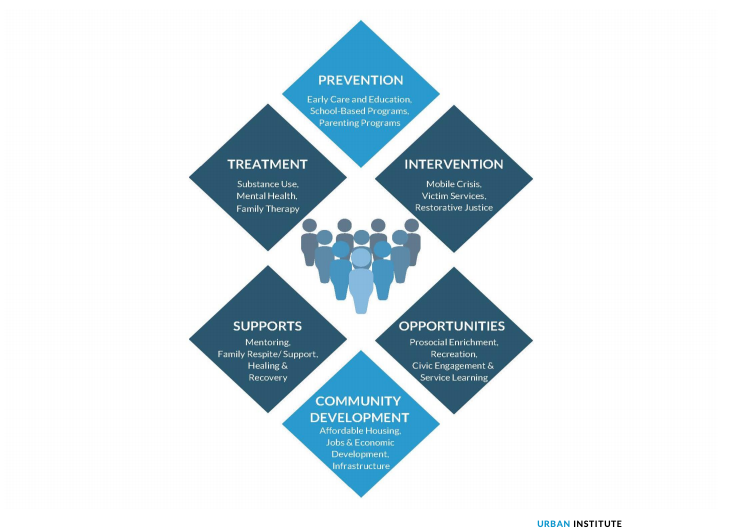

A new report from the Urban Institute offers guidance for local jurisdictions on how to repurpose juvenile detention facilities, as well as how to “capture and redirect” savings from reduced reliance on incarceration, while maximizing state and federal funding streams to create a “continuum of care” for youth and families in their own communities.

“Communities across the country are increasingly embracing community-based strategies to prevent and address harmful youth behaviors and looking for ways to fund them,” said Dr. Samantha Harvell, one of the report’s authors at the Urban Institute. “This report offers a menu of options that jurisdictions have used to fund community-based public safety solutions and covers a range of innovative ideas, from redirecting savings from youth prison reduction to levying a new tax.”

The ideal continuum of care, according to the report, includes crisis services, access to physical and mental health care, victims’ services, violence prevention programs, substance use treatment, educational and vocational supports, mentoring, therapy, and parenting and life skills classes, among other strategies.

The report highlights California’s Youth Justice Reinvestment Fund, started in 2018, to improve outcomes for juvenile justice system-involved youth through trauma-informed diversion and community-based services. A first batch of $37.3 million will be awarded to local governments to launch “evidence-based, trauma-informed, culturally relevant, and developmentally appropriate diversion programs in underserved communities with high rates of juvenile arrests and high rates of racial/ethnic disproportionality within those juvenile arrests.”

Savings realized through this system can also be reinvested, funding more community programs, and creating a self-sustained funding stream.

In other jurisdictions, reduced spending on juvenile lockups has meant more money to invest in community-based solutions.

From the millions Washington D.C. saved reducing juvenile incarceration, arose a mentoring program that paired juvenile justice system-involved kids with adults with similar histories who could provide mentorship and guidance.

The Urban Institute report also suggests local governments consider repurposing shuttered juvenile camps and halls. In 2016, the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention estimated that there were 1,300 fewer juvenile lockups in operation than in 2000.

Repurposing those facilities can relieve “taxpayers of the financial burden of facility structure upkeep” while “creating a new community resource to fulfill a previously unmet need.” Additionally, transforming these facilities means they won’t be reopened as lockups for kids or adults in the future.

In Los Angeles, county leaders are repurposing camps into residential job training centers.

A North Carolina nonprofit organization is working to create a replicable model of a prison “flipped” into a farm and education center. This model aims to help improve youth outcomes by offering education and vocational training, while “ensuring sustainability by teaching lifelong skills and promoting healthy lifestyles through the provision of fresh, locally grown produce.”

Cities and counties can also sell or lease the land on which empty prisons, jails, and juvenile detention facilities sit. That money can then be funneled into community-based services.

In the city of Whittier, CA, for example, a former juvenile facility on 75 acres was sold to a developer and turned into 750 homes, in an effort to address the city’s housing shortage.

In Texas, leased land brings in $1 million annually. That money goes to counseling and education services for local kids.

Local governments can also generate new money by implementing new taxes, redirecting money from marijuana legalization, and implementing “pay for success” programs, among other strategies.

A tax in Oakland generates approximately $8 million per year for violence prevention, according to the report.

Finally, cities and counties must look at federal and state funds that support youth and families in other ways–through health care, child welfare, housing, workforce, and other systems. “The population of youth and families accessing services from different systems including juvenile justice, child welfare, housing, and public health overlaps significantly,” the report states. “These systems share responsibility for collaboratively addressing the needs of youth clients and their families, and state and federal funding streams outside the juvenile justice system can and do support services for youth who are, or are at risk of becoming, justice-involved.”

These funds can be combined, maximizing their benefit at the community level to create a continuum of care.

“Now is the time to end our reliance on youth incarceration and instead invest in community-based solutions which we know work better,” said Liz Ryan, President and CEO of the Youth First Initiative. “We have long had the research that shows incarceration does more to hurt justice-involved youth than help. Now, we have the strategies and success stories to show how community-based care is not just possible but a winning strategy for communities and kids most affected by the youth justice system.”

Get this and other essential justice stories delivered directly to your inbox by subscribing to The California Justice Report, WitnessLA’s weekly roundup of news and views from California and beyond. Read past editions – here.