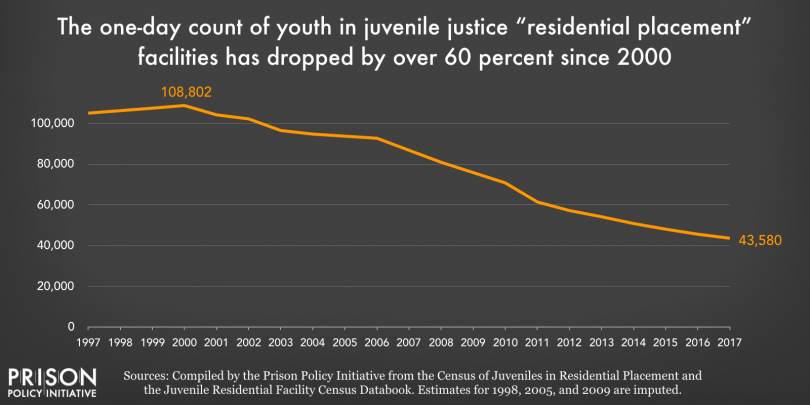

Between 2000 and 2019, the rate of youth incarceration dropped approximately 60 percent, and, during the same period, just under 1,300 juvenile corrections facilities were shuttered.

The massive decarceration shift came in response to research, reforms, and drastic drops in youth violence rates.

Now, more than 48,000 kids are in juvenile halls, camps, and prisons across the U.S. on any given day, according to the Prison Policy Initiative’s annual “whole-pie” analysis of youth incarceration in the U.S.

Despite this progress, at least 13,500 (more than a quarter) of the nation’s 48,000 incarcerated kids could be kept out of lockup without endangering public safety, according to PPI’s “most conservative estimates.” Racial disparities remain stubbornly embedded in the juvenile system, as well.

The report, written by PPI Research Director Wendy Sawyer, breaks down where, why, and how minors are kept in correctional settings.

Approximately 10,800 kids are serving sentences in long-term secure juvenile facilities, while 4,500 kids charged as adults are locked up in adult prisons and jails, and nearly 16,900 are in detention centers. Two-thirds of America’s confined kids are held in these three most restrictive settings.

Another 15,400 youth are in what are considered “residential” style facilities.

Some of these facilities, like LA County’s “model” facility, Campus Kilpatrick, offer more therapeutic and less restrictive conditions than others that may be categorized as “residential,” but which PPI notes can actually be worse than adult prisons.

In her report, Sawyer says that “for many youth, ‘residential placement’ in juvenile facilities is virtually indistinguishable from incarceration.”

Nearly all of the 48,000 kids locked up on any given day are held in locked facilities. And most of those kids “experience distinctly carceral conditions,” Sawyer writes.

More than 80 percent of locked up minors are held in facilities with more than 21 youth “residents.” And more than half are locked up with at least 51 residents, according to the report.

These rates are significant for a number of reasons, one of which is that rates of sexual victimization are higher in facilities with more than 25 youth.

Earlier this month, the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics released a report revealing that 7.1 percent of incarcerated youth reported that they were sexually victimized by staff or other kids during the previous 12 months.

“Confinement remains a punishing, and often traumatizing, experience for youth who typically already have a history of trauma and victimization,” Sawyer writes.

And while some youth will spend a short time behind bars, two-thirds of kids incarcerated on any given day will be held for more than a month, one-fourth will be locked up for more than 6 months, and approximately 8 percent (4,000) will be confined, away from their homes and families, for over a year.

Additionally, over a quarter of incarcerated youth are not even serving a sentence. More than 9,500 kids are being held while they await a hearing in court. And 6,100 more are awaiting sentencing or placement.

More than 8,000 children are locked up for technical probation violations and “status” offenses that wouldn’t be illegal if an adult committed them.

“These are youth who are locked up for not reporting to their probation officers, for failing to complete community service or follow through with referrals — or for truancy, running away, violating curfew, or being otherwise “ungovernable,” the report states. “Such minor offenses can result in long stays or placement in the most restrictive environments.” Nearly half of the kids in this category are confined for more than 90 days.

Another 1,700 kids are incarcerated for drug offenses other than trafficking, and 3,300 for public order offenses that didn’t involve weapons.

“The fact that nearly 50,000 youth are confined today — often for low-level offenses or before they’ve had a hearing — signals that reforms are badly needed in the juvenile justice system,” Sawyer writes.

These are the incarcerated populations that PPI says could be cut drastically.

Utah and Massachusetts, for example, have made status offenses “non-jailable.” The report also points to California, Texas, and other states that have enacted model-worthy reforms to keep kids in their communities and out of lockup.

Pre-arrest diversion that allows kids to avoid incarceration and prosecution altogether is one important way states can continue the critical work of juvenile decarceration, according to the report. Over a period of a year, nearly 10,000 Floridian youth were diverted from the juvenile justice system in this way.

States should also remove all minors from dangerous adult prisons and jails.

Additionally, the report calls for further increases in community-based alternatives to incarceration, caps on community supervision sentences, and trauma-informed treatment and other services.

Many of these reforms, too, can be transferred to the adult justice system, where decarceration rates have been far slower over the past two decades.

We should let them all out and move them into Taylor’s neighborhood.