This is the third in a multi-part series about racial and economic disparities in LA County’s child welfare system, and the impact family surveillance and separation has on kids and their parents.

Mandated reporting laws have led to a flood of calls to report suspected child abuse and neglect, burying calls about kids who are in critical danger, while subjecting many more families whose children are safe to unnecessary surveillance and separation.

The hotline and mandated reporters

Each month in Los Angeles County, the Department of Children and Family Services’ Child Protection Hotline receives approximately 16,000 phone calls about child abuse and neglect. Social workers manning the hotline system then assess which calls should be investigated.

In 2022, 82.5 percent of the hotline’s reports came from “mandated reporters” — teachers, doctors, therapists, childcare providers, police, and other professionals required by state law to report suspected child maltreatment. Just 16 percent of those reports resulted in social workers substantiating allegations of abuse or neglect.

In 1962, a group of doctors published an article called “The Battered-Child Syndrome,” in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). This influential article, which presented the first medical designation of the harmful effects of abuse on children, suggested medical professionals be required to report suspected abuse to law enforcement or child protective services. As a result, between 1963-1967, all 50 states passed laws creating mandated reporters.

In 1974, federal lawmakers enacted the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), which required states to have mandatory reporting laws in order to get federal grants to create and run child protection agencies as well as child abuse hotlines.

Originally, mandated reporting laws were meant to protect children from physical abuse, but were gradually expanded to include sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect.

Since the arrival of those first mandated reporting laws of the 1960s, child abuse and neglect hotline calls from those legally required to make reports and other concerned individuals have skyrocketed.

In 1963, the first year that states began to introduce mandated reporting laws, people made approximately 150,000 reports to hotlines nationally. In 2009, people called hotlines 3.3 million times, marking a more than 2000% increase in referrals over 46 years. By 2019, the number had jumped even further, to 4.4 million.

Interestingly, in recent decades, child abuse and neglect rates have declined nationwide.

From 1992 to 2009, substantiated cases of physical abuse and sexual abuse dropped 56% and 62%, while instances of neglect dropped by 10%.

In California, a mandated reporter who suspects that a child is being abused or neglected but fails to call DCFS is guilty of a misdemeanor and subject to up to six months in jail and/or up to a $1,000 fine. For this reason, concern about being held responsible may be one factor behind the monthly flood of calls from people legally required to report mistreatment.

If a person legally obligated to report fails to call the hotline, and the abuse or neglect leads to the child’s death or to great bodily injury, the mandated reporter faces a year of incarceration and a fine of up to $5,000.

Theoretically, the mandated reporting system flags dangerous abuse that might otherwise go unaddressed. Yet, it also appears to have the effect of subjecting low income families and families of color to a level of surveillance that rich white families don’t experience.

Furthermore, due to the sheer number of reports, the most urgent calls — where kids are in serious physical danger — can end up buried in a sea of reports that don’t warrant DCFS intervention.

When mandated reporting hurts, rather than helps, kids

A 2017 study found that universal mandated reporting drastically increased the total number of abuse and neglect reports while not actually increasing the number of confirmed reports. In other words, implementing universal mandated reporting appears to increase the rate at which people submit reports with little or no evidence that a child has been harmed.

In Los Angeles, when eight-year-old Gabriel Fernandez and ten-year-old Anthony Avalos were tortured to death by their parents in 2013 and 2018, multiple mandated reporters called the child abuse and neglect hotline to tell DCFS they believed the boys were being harmed at home.

Their deaths were not due to a lack of mandated reports, writes Richard Wexler, child welfare expert and Executive Director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. “they had to do with a failure to follow up on the reports, quite possibly because the system was so overloaded.”

In her book, Torn Apart: How the Child Welfare System Destroys Black Families and How Abolition Can Build a Safer World, author Dorothy Roberts argues that there is something “drastically wrong” with a system that breaks up families when kids are safe, while letting kids in “grave danger” slip through the cracks.

“The problem isn’t that there are too few people mandated to report their suspicions, too few caseworkers patrolling neighborhoods, or too few children taken from their homes,” Roberts writes.

The problem, she says, is that subjecting families to increased levels of surveillance and separation “intensifies their bad outcomes.”

Deaths of children like Gabriel Fernandez and Anthony Avalos, who were both known to the system, aren’t a testament to the need for more family policing, writes Roberts. “They prove that family policing doesn’t keep children safe.”

The threat of a doctor’s report

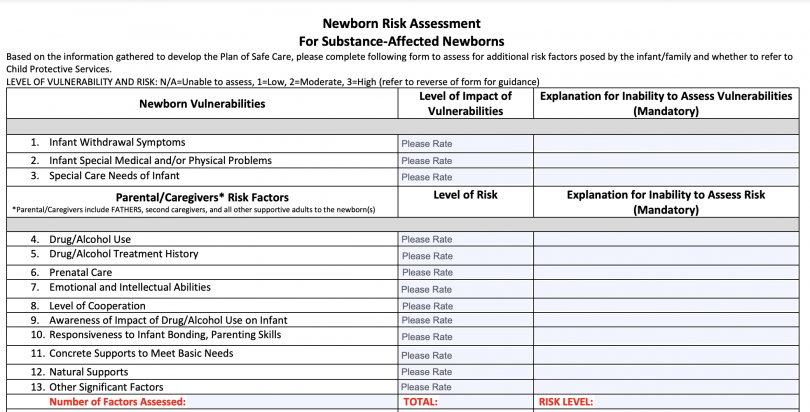

Some of the public spaces with the most robust systems of family surveillance are hospitals and doctor’s offices, where prenatal drug tests and misdiagnosed ailments can lead to unnecessary family separation.

It is not uncommon for parents to lose their children after seeking medical care for illnesses or accidental injuries.

As part of a collaborative investigation into the issue in 2019, NBC News and Houston Chronicle reporters spoke with 300 families from 38 states who said they had been accused of abuse based on inaccurate or exaggerated reports from doctors.

One set of parents lost both their young children after their five-month-old rolled off a chair onto concrete and fractured his skull. At a Houston hospital, a doctor training to be a child abuse pediatrician misdiagnosed the baby’s skull fractures and internal bleeding as having come from two separate injuries, suggesting that the parents may have intentionally harmed their child.

Based on the doctor’s child abuse report, social workers submitted the kids to the trauma of sudden separation from their parents, and months of turmoil. Five months later, a judge returned the kids, and ordered Child Protective Services to retrain their investigators and pay $127,000 in sanctions.

“Ironically,” the judge told NBC and the Houston Chron, “by the time we got to court, the kids had been injured, but not by their parents, by the state.”

Taking newborns

Mothers who use substances while pregnant report being afraid to seek prenatal care, as medical care providers are required to report to the child welfare system when they suspect an infant has been exposed to drugs.

Statistically, Black mothers and their infants are more likely to be drug tested before and after birth than babies and mothers of other races. This racial disproportionality arises from the fact that most hospitals leave whether to drug test up to the discretion of medical staff, leaving the door open for implicit bias to influence decisions.

Even when hospitals’ policies require the testing of all pregnant people and babies, that practice can lead to the unnecessary separation of families.

Additionally, medical professionals often drug test pregnant people without first obtaining informed consent.

And drug tests can return false positives.

For example, the ACLU and National Advocates for Pregnant Women sued a Chicago area hospital after staff drug tested a new mother in 2021 without her knowledge and accused her of using opiates.

The mother had eaten a piece of cake with poppy seeds.

Because of this erroneous test result, social workers spent three months surveilling the family.

“I never imagined that enjoying a traditional Polish cake at an Easter celebration would create suspicion that we would not care for our child,” said the mother, identified as Ms. F. “My husband and I wanted a child so much and we were overjoyed when I became pregnant. But the actions of the hospital took away that joy and made us feel ashamed – like we had done something wrong.”

Poppy seeds aren’t the only legal substance that sets off drug test alarms. Common psychiatric medications like Wellbutrin can falsely indicate amphetamine-use. Zoloft has shown up as LSD on drug tests. Even certain baby soaps and anti-inflammatories like ibuprofen and naproxen can indicate cannabis-exposure.

“…Routine drug testing and reporting of pregnant patients is never justified in light of the harmful consequences for families,” according to Emma Roth, staff attorney at Pregnancy Justice, the organization litigating the case alongside the ACLU of Illinois.

What happened to Ms. F. is not a solitary incident.

The ACLU has sued hospitals on behalf of other new mothers, including two mothers in New York and two in New Jersey, accused of drug use after eating poppy seeds.

Yet, even when tests accurately alert doctors to a mother’s drug use, the results don’t automatically mean a parent is incompetent or neglectful.

In a University of Florida study of infants born with cocaine in their systems, the babies who were subsequently sent to foster care were less likely to meet important markers of infant motor development by — like sitting up, rolling over, and smiling — than babies who were left with their mothers. “For the foster children, being taken from their mothers was more toxic than the cocaine,” child welfare expert Richard Wexler wrote in reference to the report.

One mother whose story we’ll share later in this series, lost all three of her children after testing positive for amphetamines at a hospital while giving birth to her youngest child in 2020.

How victims of domestic violence lose their kids

The mandated reporting system also discourages mothers who experience domestic violence from reporting their own abuse to medical professionals and law enforcement for fear of having their children taken away.

“Lacie,” a mother who asked to remain anonymous, lost her children in 2020, after her son told his teacher, a person he trusted, that he had seen his mother and her boyfriend fighting, and that it had scared him. Mandated reporting laws required the boy’s teacher to submit a report to DCFS, triggering an investigation.

In other instances, when police respond to domestic violence calls, they have to decide on the spot whether to involve DCFS. Often, their status as mandated reporters means that they do call in social workers whether or not they believe it is in the children’s best interest.

According to DCFS data obtained by the Reimagine Child Safety Coalition and shared with WitnessLA, during FY 2019-2020, social workers removed 1,017 kids from their families after law enforcement called the agency about incidents of domestic violence.

In total, police referred 30,384 kids to DCFS in 2019-2020. In 1,017 of those cases, kids were removed due, at least in part, to domestic violence in the home.

In 1998, the National Research Council found no evidence that mandated reporting makes children safer.

“Mandatory reporting requirements were adopted without evidence of their effectiveness,” wrote the council. “No reliable study has yet demonstrated their positive or negative effects on the health and well-being of children at risk of maltreatment, their parents and caregivers and service providers.”

With this in mind, the NRC recommended that states should not include domestic violence, in particular, in their mandated reporting laws until rigorous research could be conducted.

Law enforcement and DCFS are inextricably linked in a great many ways.

Several of the families WLA spoke with only became involved with DCFS after coming into contact with law enforcement, including Princess Dale, whose story we introduced in Part 1 of this series.

In Part 4 of this series, we’ll take a look at some of those family policing connections, including a little-known partnership through which DCFS and the Los Angeles Police Department conduct raids together.