During its pilot period, Los Angeles County’s Family Assistance Program was a welcome help to dozens of families whose loved ones died in custody or during encounters with law enforcement, according to a report from the Office of the Inspector General.

Yet, facilitators struggled to boost awareness of the program. For this and other reasons, it often took longer than intended to disburse funding set aside for funerals and other support to the families who needed it.

Meanwhile, families continued to report insensitive treatment from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD).

Still, Inspector General Max Huntsman believes the program should continue, with improvements and with more funding.

In July 2018, the civilian commission overseeing the sheriff’s department (COC) developed an ad-hoc committee to investigate how the LASD interacts with the families of those who are killed after contact with the department – with the goal of improving department practices.

That committee spoke with individuals and families that lost their loved ones, as well as community organizations and the county departments that interact with families after a deadly incident.

In doing these interviews, the committee members found that it was common for families to be left without adequate information regarding the circumstances surrounding the death of their child, parent, sister, brother or other family member. Additionally, families reported that they were often treated clumsily by law enforcement, and did not receive sufficient support to address the trauma they experience following the crushing loss of someone they love.

(Grieving families, especially those who filed lawsuits against the sheriff’s department, have also reported harassment from members of the LASD, both to the board of supervisors and the Civilian Oversight Commission (COC). The board has addressed this separately.)

Setting up the Family Assistance Program

With these problems in mind, the COC’s ad-hoc committee developed a set of recommendations for county officials and the sheriff’s department. Within that list was a recommendation to establish a program to assist families with funeral costs and other financial needs “including trauma and grief counseling,” after an in-custody death or fatal encounter with members of the sheriff’s department.

In July 2019, in response to the committee’s findings, the LA County Board of Supervisors approved a motion to pilot the Family Assistance Program. The program was to run one year, with a one-time infusion of funding.

Because the county had trouble getting the program running properly, and used a fraction of the money set aside for family assistance during the pilot year, the financial portion of the program was extended until the full $180,000 budget was distributed to survivor families.

As part of the planned Family Assistance Program, the 2019 motion directed the Department of Mental Health to hire Family Assistance Advocates (FAAs) to act as the primary liaison for families grieving a loss. The job of each FAA was to “communicate timely updates to families, help families navigate the county’s process, identify resources that may be available to them, including funds to assist with burial costs, and provide crisis intervention, stabilization and grief counseling.”

The sheriff’s department, coroner’s office, and other relevant departments were directed to select staff members to work with the FAAs to ensure families received “timely, coordinated, and respectful information” about the death of a loved one and the investigation into the death.

During that July 2019 board meeting, and during other meetings before the Civilian Oversight Commission, family members told stories of grief and financial hardship brought on by their loss. Parents, siblings, and grandparents also told stories of finding out that their son or daughter or sibling or grandchild had died, via the news or from social media. One mother said a member of the sheriff’s department left her a voicemail telling her of her son’s death.

Yet, despite efforts to improve the treatment families receive, some say little has changed, and they are experiencing the same problems.

Delayed next-of-kin notifications

After the official pilot program’s conclusion, the family of Destiny Ortega, who died inside LA’s women’s jail on December 29, 2021, said they were not notified of Ortega’s death.

Ortega, a 32-year-old mother of three, was arrested over an alleged parole violation one day earlier, on December 28. Deputies reportedly found her lying in a pool of blood in her cell with head and body injuries. Her cellmate, found lying in her bunk, reportedly refused to talk to officers.

Ortega’s family said they were unaware until a week later, when they saw social media links to news stories about her violent death.

“The facility failed to make contacted(sic) with a family member,” Ortega’s cousin Ariel Malta wrote on a GoFundMe page for the family.

“And NOW a week later on January 7th, my family and I were aware of this tragedy through social media from a Facebook post from KTLA & LA TIMES.”

(As of this writing, the page has raised $1,297 of a $10,000 goal to pay for an attorney to look into how Ortega died.)

IG Huntsman’s report says that LASD Homicide Bureau continued to conduct next-of-kin notifications throughout the pilot. The Department of the Medical-Examiner/Coroner would prefer to have the responsibility for making first contact, Huntsman said, but “lacks the funding and staff to do so in a way that ensures it has the resources to quickly start an investigation to locate family members” and provide a proper notification.

The Department of Mental Health accompanied the LASD on some next-of-kin notifications while the program was in effect, but never gate the notifications themselves.

The Inspector General, in his report, said he believed the program would be most helpful to families “if initial notification of death is made either by Family Assistance representatives, or if the [Department of the Medical Examiner/Coroner] employs trained social workers and an additional investigator to provide next-of-kin notifications with the support and assistance of the [Office of Violence Prevention (OVP)] and its community partners.”

Those Family Assistance Advocates from the Department of Mental Health “were often unable to obtain information about the circumstances of deaths for weeks following a death,” according to Huntsman. “This made it difficult for advocates to offer meaningful support to families who had questions” about how their loved ones died.

Partly, the FAAs were blocked by the sheriff’s department, which cited the need for privacy around active investigations. It’s not uncommon, after an in-custody death or a fatal shooting, for families to wait months for information.

Additionally, at a community listening session in November 2021, the inspector general, civilian oversight commission, and Office of Violence Prevention heard from community members whose family members were killed by law enforcement.

Some attendees said it was the first time they were hearing of the program, and suggested more robust outreach. That outreach, the speakers said, should come from community-based organizations, rather than the sheriff’s department or other county staff working with the LASD. Families said members of the LASD with whom they were in contact about the deaths acted as if their deceased loved ones were criminals and their family members were “co-conspirators.”

Others urged those listening to extend the program to support those grieving deaths that occurred before the program’s 2019 inception.

Valerie Vargas, whose nephew Anthony Vargas was killed by members of the LASD in 2018, months before the Family Assistance Program launched, said that her family was told they didn’t qualify for assistance. The Vargas’s are among a number of families who have accused the department of harassment and have filed wrongful death lawsuits against the LASD.

On August 12, 2018, deputies shot and killed 21-year-old Anthony Vargas after pursuing him and wrestling him to the ground. In June 2019, a leaked autopsy report showed that that, contrary to initial LASD descriptions, the deputies shot Vargas 13 times from behind.

Noting that her nephew had died a few months before the program’s implementation, Valerie Vargas asked if there was a statute of limitations families must meet to receive services. If the COC could verify the date limits, she said, she could pass the information on to others.

“I’ve had a few families asking me about the Family Assistance Program,” she said. “I have yet to meet one that has actually received any sort of assistance.”

“We never intended any kind of statute of limitations in the original construction [of the program], said Patti Giggans, the executive director of Peace over Violence and a commissioner on the COC. Thus, she said, she hoped that intention would be clarified in the development of the permanent program. “We’ve been working on getting rid of statute of limitations for a lot of things, so I would hope that we wouldn’t include one on this program.”

Some called for regular status updates on the availability of body camera footage, autopsy results, and other information about death investigations.

Moving forward

Despite its troubled start, the program was a success in one important way, according to the report. The Family Assistance Program provided support to a total of 45 families (40 percent of all eligible families).

Twenty-one families received connections from the Department of Mental Health to community organizations and mental health services, and 24 others received financial assistance with burial expenses — up to $7,500.

In October 2021, the county supervisors directed the CEO to find bridge funding to make sure that money continues to be available for burials until the program and its funding are made permanent.

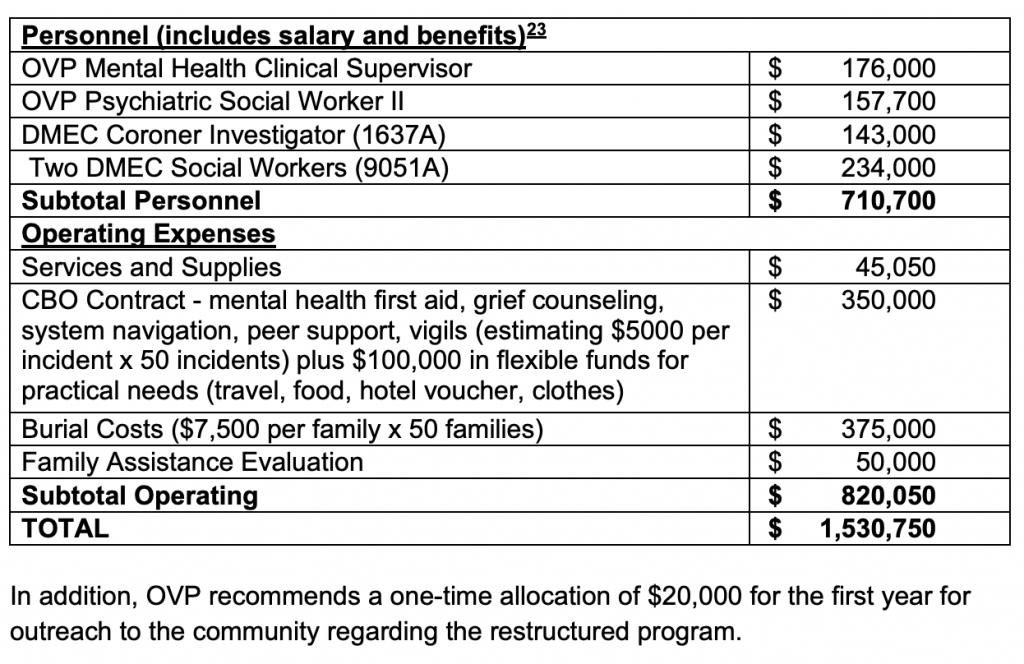

A recommended annual budget for the program, developed by the Office of Violence Prevention, calls for $1.5 million between personnel and operating expenses, within which $375,000 would go toward burials, and $350,000 would go to community based partners providing things like mental health care, grief counseling, peer support, and assistance with vigils.

OVP will also develop a comprehensive data system for tracking the number of families served, the ways in which they were served, and when.

This data “will allow OVP to both examine the countywide impact of deaths involving the Sheriff’s Department and to evaluate Family Assistance’s accomplishments and make recommendations for policy, practice, and system changes,” Huntsman wrote.

The county’s proposed schedule would see the restructured program launched over the summer of 2022.

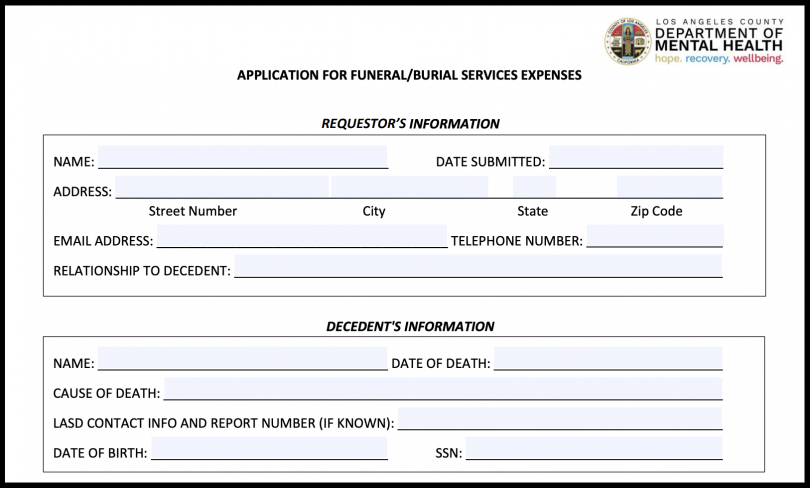

Image: Family Assistance Program Funeral Assistance Request Form, Department of Mental Health.

Hello it’s Stephanie Oceja again I finally got in contact with Destinys family can you please delete my public comment due to the fact that my phone number is exposed please and thank you.

Editor’s note:

Hi, Stephanie. I’m glad you found Destiny’s family. As you can see, the earlier comment is gone.

Take care.

Celeste