On Monday morning, CBS released a poll looking at how Americans view the newly-looming specter that Roe v. Wade is likely going to be overturned this summer by the U.S Supreme Court.

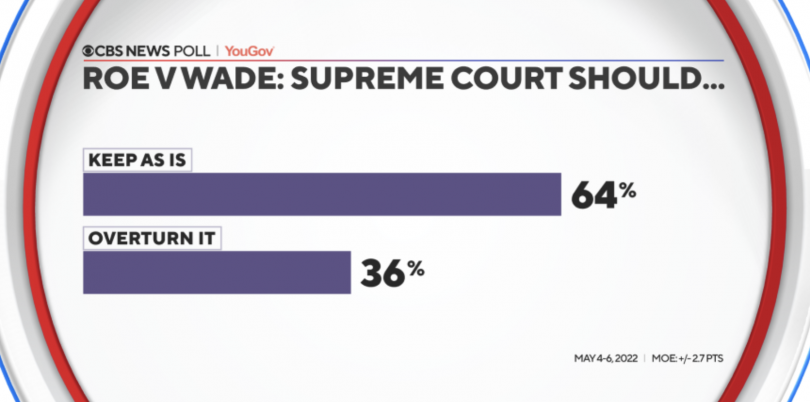

In today’s survey, CBS found that close to two-thirds of Americans want Roe kept in place as is. And most of that two-thirds who favor the half-century of protection of women’s right to choose whether or not to keep a pregnancy, say they “feel angry and discouraged about the prospect that it may be overturned,” describing the oncoming loss of the protection of Roe as “a danger to women” and as a threat to rights more generally.

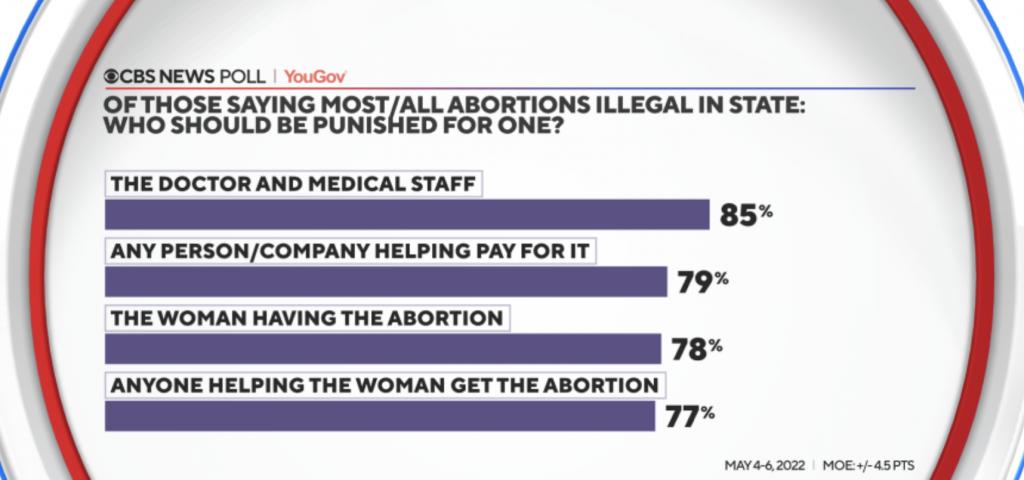

Yet, the minority of Americans who said they favored abortions being illegal in their states also said that the women who chose to end a pregnancy, should be subject to criminal prosecution along with those who provide any illegal abortions, whether surgical or via medication.

This brings us to the story below by Christine Vestal of Stateline, an Initiative of Pew Charitable Trust, about what some states, including California, are doing to protect against such prosecutions. So read on.

Does the looming SCOTUS decision, along with ever-more aggressive state abortion laws, mean an increasing risk of prosecution for people who self-induce abortion?

By Christine Vestal of Stateline, Initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Last month, 26-year-old Lizelle Herrera was arrested in Texas and charged with murder over a self-induced abortion.

A hospital had reported the abortion to law enforcement. But prosecutors later acknowledged she shouldn’t have been prosecuted and dropped the charge. “In reviewing applicable Texas law, it is clear that Ms. Herrera cannot and should not be prosecuted for the allegation against her,” Starr County District Attorney Gocha Allen Ramirez said in a news release.

If the U.S. Supreme Court weakens or overturns the right to abortion as expected in the months ahead, health advocates warn that more people who manage their own abortions using U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved medications, herbal remedies or other non-medical methods will be falsely arrested on charges of violating abortion bans, homicide laws and other criminal statutes.

The justices have voted to strike down Roe v. Wade, according to a draft majority opinion written by Justice Samuel Alito that circulated inside the Supreme Court in February and was obtained by Politico. “Roe was egregiously wrong from the start,” Alito wrote in the leaked draft. Justices could change their votes during deliberations, and the decision won’t be final until published, but it revealed the court’s thinking.

“Once federal protection of abortion is gone,” said Drexel University law Professor David Cohen, “we can expect to see more overzealous local prosecutors taking aggressive actions against people for self-managed abortions and other pregnancy outcomes.”

Lawmakers and criminal justice officials in a handful of states are trying to prevent these rogue legal actions, which conflict with current state laws and in all but a few cases have been overturned by courts. But even in left-leaning states, the new efforts have faced pushback, and advocates fear more women will be charged.

Ever since the Supreme Court guaranteed the right to abortion in its 1973 decision, state laws restricting the procedure have held abortion providers, not pregnant people, responsible. Even before the landmark ruling, state laws stopped short of holding pregnant people responsible for the procedure, according to legal scholars.

But prosecutors who have charged women with self-induced abortion have argued they violated a variety of other state laws, including manslaughter, fetal homicide and homicide by child abuse, according to research by National Advocates for Pregnant Women, a nonprofit that provides legal defense for pregnant women.

Physicians, public health officials and women’s advocates have long cautioned that arrests for self-managed abortions and miscarriages will disproportionately stigmatize low-income people, immigrants and women of color who already lack access to reproductive health care.

The number of such cases has been rare: roughly 1,700 arrests and other legal actions since 1973, including surveillance and child services interventions, according to National Advocates for Pregnant Women. But legal experts and civil rights advocates think that attempts to prosecute women for self-managed abortions will rise as state abortion bans tighten and more women choose to end their pregnancies on their own.

“It has never been politically popular to enact laws that punish women for abortions,” Cohen said. But as more states ban the procedure, local prosecutors will likely become emboldened to take matters into their own hands, he said.

States aim to stop prosecutions

California Attorney General Rob Bonta, a Democrat, warned state law enforcers in January not to use the state’s homicide laws or other statutes to punish individuals for self-managed abortion or other pregnancy loss.

In an April 27 letter, he urged attorneys general in all 50 states to alert law enforcement officials similarly to refrain.

“For years, state actors across the country have subjected individuals experiencing pregnancy to improper and discriminatory criminal prosecutions, detention and surveillance,” Bonta wrote.

“Criminal statutes meant to protect people who are pregnant from the violent acts of others have been misapplied to penalize them for any number of activities” that may result in harm to a fetus or a pregnancy loss, he wrote.

In April, Colorado enacted a broad reproductive health law that, among other protections, ensured that a person could not be prosecuted for pregnancy-related death or harm to a fetus. Washington state enacted a law in March that protects people seeking an abortion and those who aid them from legal action from the state.

In 2019, Illinois and New York enacted provisions excluding a pregnant person from fetal homicide laws, and Rhode Island repealed its fetal homicide law.

This year, lawmakers in California and Maryland have considered similar bills, clarifying that a person may not be punished for the death of a fetus due to any acts or omissions during their pregnancy or shortly thereafter.

Although mainstream anti-abortion groups agree with abortion rights advocates that homicide and other state statutes should not be used to punish pregnant women for abortion, the bills aimed at protecting them from prosecution have met fierce opposition in both California and Maryland.

In both states, opponents claimed that a provision in the proposed law, which would exempt pregnant people and medical professionals from prosecution for the death of an infant shortly after birth due to pregnancy complications, was tantamount to legalizing infanticide.

Both bills would prohibit prosecution of or civil lawsuits against a pregnant person for pregnancy-related harm or death and allow victims of spurious arrests to sue their prosecutors. The California bill remains active this session, but its likelihood of passage is uncertain. The Maryland bill was in a committee when the state’s session ended last month.

Roughly three dozen states have fetal homicide laws that increase penalties or create a separate crime when a violent attack on a pregnant woman results in the death of a fetus, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. In most of the states, the wording of feticide laws explicitly excludes the pregnant woman from any fault.

New laws and bills in states that aim to protect people who self-manage their abortions are meant to underscore what most fetal homicide laws already make clear.

Disproportionate harm

Herrera, the Texas woman who was arrested on a murder charge related to a self-induced abortion, was released after three days when a local district attorney ruled her case invalid. But the repercussions of her case extend well beyond the border town where she was jailed.

Medical professionals say they worry that media attention to her case and others, as well as the looming Supreme Court decision that could allow abortion to become illegal in more than half of the country, will create widespread fear among low-income and marginalized people who already are disproportionately targeted by law enforcement and lack adequate access to health care.

“Once strict abortion laws take effect, we can’t completely rule out the possibility of unsafe abortions,” said Dr. Jamila Perritt, CEO of Physicians for Reproductive Health, which advocates for equal access to reproductive medical care, including abortions.

“But with greater access to online medications, the risk is much less than it used to be. Self-managed abortion can be safe and effective,” she said. “The risk is not a medical one, it’s a legal risk.”

Herrera’s arrest was a direct result of a hospital reporting an abortion to law enforcement. The same is true for the vast majority of people arrested for self-managed abortion, miscarriage or stillbirth, Perritt said.

Most people do not need to see a doctor or go to a hospital when taking medication to induce an abortion. They can complete the procedure in the privacy of their homes. But for those who do need medical care, fear of arrest should not be a deterrent, she said.

Last year, the American Public Health Association published the results of a survey of more than 7,000 women, showing that self-managed abortion was nearly three times more prevalent among Black women than White women and somewhat higher among Hispanic women. According to the public health association, the results indicate that women of color “may face heightened barriers to accessing clinical care or prefer self-managed abortion due to experiences of stigma, discrimination, and structural racism.”

Major medical organizations, including the American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have decried the criminalization of pregnant people for abortion and warned medical professionals not to report a patient for the loss of a pregnancy, which they say violates privacy laws and medical ethics.

Medication abortions drive concerns

Despite recent declines in the total number of abortions, due in part to increased access to contraception, nearly 1 in 4 women in the United States will have an abortion by age 45, according to research organization the Guttmacher Institute, which advocates for abortion rights. Medical abortions accounted for more than half of all abortions in 2020, according to a Guttmacher report published in March.

As medication abortions have risen, so have state laws attempting to limit their availability. April Lockley, medical director of the Miscarriage and Abortion Hotline, said her organization was founded to help women manage the process on their own. Recently, she said, the group has been fielding a growing number of calls from women who are unsure whether medication abortion remains legal in their state.

In Texas, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott signed a law that took effect Dec. 2, making it a felony to provide the pills after seven weeks into a pregnancy or to ship the pills through the mail.

The rise in medication abortions, combined with more aggressive state abortion bans in the last two years, spells increasing risk of arrest and prosecution for people who self-induce abortion, said Farah Diaz-Tello, senior counsel and legal director of If/When/How, a group of national advocates for reproductive justice that represented Herrera in the recent Texas case.

“Increasingly strict state regulation of abortion providers has driven many providers out of business. That train has left the station, and it isn’t coming back,” Diaz-Tello said. “More people are going to be self-managing abortions, and more people are going to be criminalized for it.”

Author Christine Vestal is a Staff Writer for Stateline, where she covers mental health, drug addiction, and related issues.

Before joining Pew she covered health care, the environment, energy, information technology and telecommunications for a variety of news outlets, including McGraw-Hill, the Financial Timesand Post-Newsweek Business Information. At Stateline, she has covered the legal and political battles over the Affordable Care Act and expansion of Medicaid to more low-income adults. She has also written about children’s health, Medicaid, mental health, wellness, and a wide variety of public health issues. Currently, Vestal is focusing on the prescription painkiller and heroin epidemic, including efforts to stem overdose deaths by making addiction treatment with medications more widely available.

This story initially appeared in Stateline, an initiative of The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Fake News