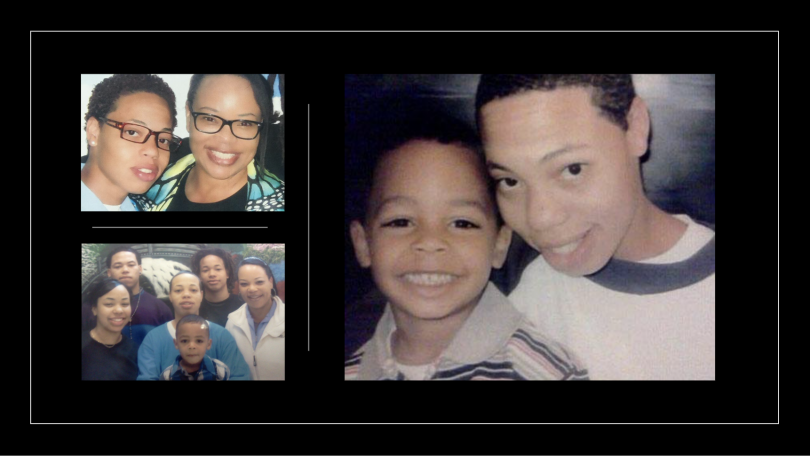

On October 6, 2022, on an unprecedented presentation to California prison officials, the mother of Shaylene Graves, a young woman killed in a women’s prison in Chino in 2016, shared recommendations for preventing intimate partner violence and suicides, especially in women’s prisons.

The presentation was part of a $3.5 million settlement agreement between Graves’ mother and son and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR).

In the days leading up to her death on June 1, 2016, Shaylene Graves was moved into a cell with Johney Davis, a person with whom Graves had a romantic relationship.

According to the Graves family’s lawsuit, and based on transcripts of interviews with witnesses, Davis reportedly became violent with Graves. On multiple occasions, Davis talked about wanting to kill Graves in common areas where other women and staff members could hear. Davis also reportedly slammed Graves up against a wall and threatened her while in line for medication.

Increasingly concerned for her physical safety, Graves asked repeatedly to be moved out of the cell she shared with Davis. She asked multiple staff members for what is called a “bed change,” citing her cell mate’s threats, and was denied each time.

For hours before her death in the early morning of June 1, people in cells nearby could hear what sounded like loud fighting. Officers in earshot failed to intervene.

No one came to check on Graves and Davis until long after the commotion had turned to silence. Emergency medical technicians arrived at the cell around 3:00 a.m., about six hours after the start of the violence, according to the lawsuit. Graves was declared dead 15 minutes later.

For months, the Graves family had to fight for information about what happened to Shaylene.

Johney Davis reportedly told officers that she woke up to find Graves hanging, and pulled her body down. However, investigating officers reportedly found that the scene appeared staged.

Despite this, during the months-long investigation, the official narrative was that Graves had committed suicide. Never informed otherwise, the Graves family did not find out that the investigation concluded Shaylene’s death was a homicide until the Graves family’s lawyer, Jim DeSimone filed a lawsuit on their behalf.

Not a safe place

During the years leading up to Shaylene Graves’ violent death, CIW experienced a high number of deaths, many of which were found to be suicides.

Between 2014 and 2016, there were at least five suicides and more than 65 suicide attempts at the California Institution for Women, a rate five times higher than the average among California’s prisons, and eight times higher than the national average for women’s prisons.

A a state-level audit in 2017 revealed serious problems with risk assessment and suicide prevention in CIW and other prisons.

That auditors listed “domestic violence in interpersonal relationships between female inmates” among the factors likely contributing to high suicide rates in women’s prisons.

The state prison’s clinical support chief explained in the report that “unlike male inmates, female inmates tend to build family units within prison, and Corrections has found that domestic violence can occur within these units.” Prison leadership was slated to develop and implement curriculum about same sex domestic violence to be offered to women receiving mental health services in prison.

In 2018, then-Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill that required CDCR to submit annual reports to the state legislature detailing its progress toward remedying the problems the audit uncovered.

Thus far, these yearly reports have not appeared to address the issue of interpersonal violence identified in the 2017 audit.

“That’s why we’re doing the presentation, why this non-monetary relief was so important,” Jim DeSimone, the Graves family attorney told WitnessLA in February 2022. “They studied the problem, they identified the problem, but then they didn’t do anything about the problem. You know?”

The money, said Sheri Graves, is not the important part of the settlement.

What Graves wants most is accountability for Shaylene’s death, for prisons to change the way staff responds to domestic violence, and oversight. “I do not want my daughter’s death to be for nothing.”

The presentation

During a virtual presentation on October 6, Sheri Graves spoke to dozens of prison officials, including members of the CDCR Gender Responsive Strategies work group, about how prisons can better protect women in custody from violence.

Graves called on the CDCR to address a “dangerous blind spot”: intimate relationships behind bars — technically illegal but generally ignored to the point of failing to respond to domestic violence within a confined population of people with high rates of past trauma and abuse.

“While sex between prisoners is illegal in California, it is still prevalent and tolerated,” Graves said. “In fact, prisons still hand out condoms! So why wouldn’t you have programming to foster positive intimate relationships, when they are so prevalent?”

Instead of only offering education around domestic violence to women receiving mental health services, prisons should offer information and services to everyone in women’s prisons considering the prevalence of romantic relationships.

Those experiencing violence behind bars should also have easy access to anonymous reporting options to non-correctional staff, to reduce fear of retaliation for “snitching” on their peers, and access to timely crisis intervention from staff trained in this area.

“The most important thing,” said Graves, in her presentation, “is for victims to know the support systems available to them; be able to report abuse in a safe way to eliminate the risk of retaliation and further abuse; and, have quick access to immediate solutions when separation from the aggressor is necessary.”

Graves emphasized the need for a “bed change policy overhaul.” Prisons should have a safe space available 24/7 to relocate incarcerated people who tell staff they fear imminent harm. And when evidence of abuse or other violence is present, prison staff must swiftly investigate and offer a much faster process for permanent bed changes.

“If there’s one thing I know would have saved Shaylene’s life, it’s being granted the bed change that night, which she tried so desperately and repeatedly to get,” said Graves. “I still don’t understand how her pleas were ignored in the face of such clear evidence of imminent violence.”

Correctional officers should also be rigorously trained to identify the signs of domestic violence.

“There is a dangerous disconnect between institutional policy, staff practices and the everyday reality of these women’s lives and relationships,” Graves said.

“In studies of prison violence in women’s facilities, inmates have shared that correctional staff usually fail to protect them from relationship-based violence because they just don’t care, downplay the danger as just part of prison life, or play favorites with aggressors,” said Graves. “They also threaten prisoners with retaliation or ‘naming names’ if they seek help or refuge.”

That culture of indifference is unacceptable, Graves said.

“If just one staff member had taken Shaylene’s pleas for protection seriously, or just taken action in response to the drinking, the violence, the verbal threats, the screaming—any of it—she would still be alive today,” she said. “There must be consequences for such failure to act.”

There must also be frequent audits to ensure staff are adequately monitoring and responding to relationship violence.

“CDCR has ignored this problem for too long, and women are still suffering and more than a few have died because prison officials turn away from the reality of women who often have a history of domestic abuse being threatened, abused and beaten in prison relationships,” said attorney DeSimone. “If it’s a crime outside of prison, it should be taken seriously inside, as well.”

It starts with these perverted men staff/ outside workers working in C. I. W.. I was in a relationship with this officer and he threatened me if I left him. I was scared at first I got what I wanted it was a game for me. Then I was frightened bc he told me he would make me loose my date and tell other inmates I was snitching.. So it starts with men staff..