“Today is a historic day,” said Jules Lobel, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), on Tuesday morning.

And so it was.

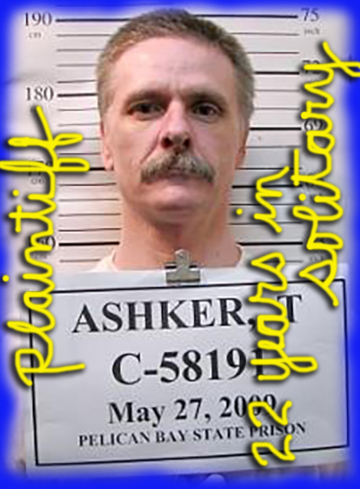

Lobel was referring to Tuesday’s announcement of the settlement of Ashker v. Governor, the class action suit brought by the CCR in 2012, that now will result in sweeping changes in the way that California prisons use solitary confinement. The lawsuit was brought on behalf of a group of ten Pelican Bay State Prison inmates who had each spent at least 10 years in solitary confinement, several of them far longer.

(This same group of plaintiffs were the primary organizers of the prison hunger strikes of 2011 and 2013, to protest the conditions of those held in solitary. The 2013 strike resulted in 30,000 prisoners refusing food during its first five days.)

When the Center for Constitutional Rights first filed Ashker on May 31, 2012, in Pelican Bay alone, more than 500 of the 1100 prisoners residing in the SHU—as solitary housing units are known—had been there for over 10 years. An additional 78 prisoners had been in Pelican Bay’s SHU for more than 20 years.

As of Monday, across the state as a whole, a total of 2,858 prisoners were reportedly locked in SHUs. In Pelican Bay, which has the largest SHU program in the state, this means they spend 22 ½ hours a day in cramped, concrete, windowless cells. They are denied telephone calls, contact visits, or any kind of programming whatsoever.

Under Tuesday’s agreement, the number of prisoners kept in solitary could fall by more than half, or as many as 1,800 inmates, according to Jeffrey Beard, the secretary of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, who talked with reporters by conference call on Tuesday.

The far-reaching agreement, as described by the Center for Constitutional Rights, in their summary of settlement terms “…fundamentally alters all aspects of this cruel and unconstitutional regime. The agreement will dramatically reduce the current solitary confinement population and should have a lasting impact on the population going forward; end the practice of isolating prisoners who have not violated prison rules; cap the length of time a prisoner can spend in solitary confinement at Pelican Bay; and provide a restrictive but not isolating alternative for the minority of prisoners who continue to violate prison rules on behalf of a gang.”

Among the most important terms of the settlement is the fact that now California will no longer impose indeterminate SHU sentences. Instead, after serving a determinate sentence for a SHU-eligible offense, validated gang affiliates whose offense was proven to be related to gang activities will be transferred to a two-year, four-step program—knowns as a step-down program. When those two years are up, if the inmates do not commit another SHU-eligible offense while in the program, they will be released to a general population prison setting. Even during the two years, although “conditions at the steps remain harsh,” explains the CCR, prisoners will be allowed some telephone calls, plus rehabilitative programming at each step.

The day after the settlement, the New York Times ran an editorial explaining the importance of the lawsuit:

Here’s a clip:

If mass incarceration is one of modern America’s deepest pathologies, solitary confinement is the concentrated version of it: far too many people locked up for far too long for no good reason, at no clear benefit to anyone.

The practice “literally drives men mad,” Justice Anthony Kennedy of the Supreme Court said in an appearance before Congress last March, highlighting the case of a California man isolated for 25 years. In July, President Obama became the first president to denounce the use of solitary. Locking people up alone for years or decades, he said, “is not going to make us safer. That’s not going to make us stronger. And if those individuals are ultimately released, how are they ever going to adapt?”

These remarks are notable only because they come from the highest levels of government. Many Americans have been aware of the horror of indefinite solitary confinement for years.On Tuesday, the slow push for meaningful reform got a big shove in the right direction. In a sweeping, unprecedented class-action settlement, California officials agreed to a drastic overhaul of the state’s solitary confinement system, the largest, most indiscriminate and most brutal in the country.

The settlement — which ends a lawsuit brought on behalf of a number of long-serving inmates — will mean the immediate release of more than 1,000 isolated inmates back into the general prison population. When the suit was filed in 2012, 500 of these inmates had been held for more than 10 years in tiny, windowless cells with virtually no human contact. At most, they had 90 minutes a day to take a shower or stand alone in a concrete “yard.” (A 2011 United Nations report said that stays longer than 15 days could amount to torture.)

The offenses that landed them in solitary? Most often, it was evidence that they were “affiliated” with a prison gang, whether or not they had broken any rules. The risk they posed to other inmates was rarely a factor. Still, they had to wait six years for a chance at review. Any evidence of continuing gang ties meant at least six more years.

By coincidence, a study on solitary was released Wednesday by the Association of State Correctional Administrators and researchers at Yale Law School, which reported that state and federal prisons are holding as many as 100,000 inmates in solitary confinement, a figure that poses a “grave problem” for the criminal justice system, said the researchers.

Jess Bravin of the Wall Street Journal, who reports on the research, notes that Colorado corrections director Rick Raemisch, who helped oversee the study, said use of solitary confinement had gotten out of control, as officials found it a convenient way to maintain order in their prisons.

“The original purpose was to take those who were deemed too violent or too dangerous in the institution and to isolate them so no one got hurt,” he said. “But as it evolved, if you didn’t follow the rules in a particular area—no violence but you didn’t act the way you were supposed to act—you were placed in solitary confinement.”

For inmates with mental illness or emotional disorders, such isolation only exacerbates their problems, making them a greater safety risk when eventually released, Mr. Raemisch said.

Solitary confinement has a long history in the U.S. and was originally instituted by Quakers and Anglicans, not as punishment, but as a time for contemplation and to seek forgiveness from God, all of which it was hoped would be corrective. Yet, when political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville came from France to investigate the U.S. penitentiary system in 1831, de Tocqueville examined the use of solitary confinement and quickly perceived the wrong-headedness of the strategy. He wrote:

“Nowhere was this system of imprisonment crowned with the hoped-for success. In general it was ruinous to the public treasury; it never effected the reformation of the prisoners.

“In order to reform them, they had been submitted to complete isolation; but this absolute solitude, if nothing interrupts it, is beyond the strength of man; it destroys the criminal without intermission and without pity; it does not reform, it kills.”

I sure do not want to hear any lawsuits from family members of these Prison Gang leaders. When they go back onto the mainline they will be targeted and killed by other inmates due to them dropping out of their gang, being snitches, working with law enforcement, etc. The prisons may blow up into full on riots if these released still have any power. You book warriors who have never stepped foot into a Prison or seen the mentality and power these SHU convicts first hand should never be allowed to express an opinion because you just write fluff pulled out of you backside. I think it would be great to send you into these prisons and try your bullsh*t on these convicts.