LAST WEEK’S LA COUNTY JAIL PLAN VOTE APPEARS TO BE IN VIOLATION OF THE BROWN ACT

The LA County Board of Supervisors may have violated the Brown Act when they voted on a proposed amendment to a large-scale plan to divert mentally ill from county jails last Tuesday. The amendment, proposed by Supe. Michael Antonovich, was to launch construction on two new jails—one, a 3,885-bed replacement of Men’s Central Jail (to the tune of $2 billion), and the other, a women’s jail renovation at Mira Loma Detention Facility.

Because the board agenda did not mention there would be a discussion or vote on the jail construction, advocates and others say the vote was illegal according to the Brown Act which guarantees the public’s right to attend and participate in meetings of local government bodies.

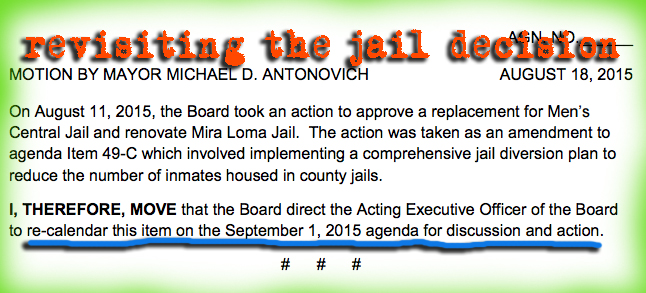

Supe. Antonovich has since submitted a motion to reconsider the jail plans on September 1, but the ACLU’s Peter Eliasberg is worried the new “ambiguous” motion also means the jail diversion plan it’s attached to will also be reconsidered, unnecessarily.

“The only thing that really needs to be recalendared and opened for comment is the board’s decision to go ahead with the jail plan,” said Eliasberg. “As far as I’m concerned, the diversion motion was properly noted and should be treated as properly passed.”

The Daily News’ Sarah Favot has more on the issue. Here’s a clip:

“We understood that there were members of the public concerned that there was not enough time to participate in the process,” Antonovich spokesman Tony Bell said Monday. “We recalendared the item to make sure anyone who wanted to provide input on this item had that opportunity.”

The vote to continue construction of a $2 billion new jail in downtown L.A. to replace Men’s Central Jail and the renovation of a women’s jail at Mira Loma Detention Facility was tacked onto a motion during last week’s meeting on the jail diversion plan.

Antonovich proposed an amendment to the jail diversion motion by Supervisors Mark Ridley-Thomas and Sheila Kuehl that would authorize contractors to continue construction on the two jails and proposed that 4,600 beds be built in the downtown jail that would house mentally ill inmates, inmates who have substance abuse issues and those who require medical attention.

Kuehl proposed a change to Antonovich’s amendment that the new jail have 3,885 beds, which was approved by a 3-1 vote with Supervisor Hilda Solis abstaining.

The diversion plan was approved by a 4-1 vote, with Supervisor Don Knabe opposed. Knabe said he wanted to have a flexible number of beds so that if the diversion efforts were successful, the number of beds in the jail could be reduced.

The agenda did not mention there would be discussion or a vote on the jail plan.

The jail plan was discussed at the Aug. 4 board meeting, but no vote was taken. At that meeting, the supervisors discussed a consultant’s report on the number of beds required at the new downtown jail facility.

During last week’s meeting, Peter Eliasberg, ACLU legal advisor, said the vote violated the Brown Act, which governs open meetings for local government bodies. He said the board opened itself up to a lawsuit.

The problematic vote riled the LA Times’ Editorial Board. Here’s the first paragraph of the board’s response:

Why does the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors even bother with agendas? Why post them, why even write them up, if the supervisors are simply going to ignore them and barge ahead with non-agendized business, approving costly and controversial projects such as new jail construction without public notice — without sufficient notice even to one another — and without serious analysis of the consequences?

We’ll keep you updated.

EDITORIAL: LA CAN’T KEEP JORDAN DOWNS WAITING FOR MUCH-NEEDED REBUILD

Plans for major reconstruction of the once-notorious 700-unit Jordan Downs housing project in Watts have been on hold for years.

The Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA) has been sitting on a $700 million plan to clean up the subsidized housing community, and add 700 more units, as well as restaurants and shops meant to provide jobs opportunities to Jordan Downs residents and the rest of the Watts community.

Jordan Downs has a history of gang violence, but is not as bad as it once was. The housing project went nearly four years without a homicide (until this April). Before that, from 2000-2011, 25 people were killed there.

Money has been spent on substance abuse treatment, community policing, child care, job training, and other programs including, Project Fatherhood. Through the Project Fatherhood program, men from Jordan Downs meet every week to teach each other, and younger men in the community, how to be fathers.

HACLA has lost out on federal funding, and is in the middle of cleaning up an adjacent toxic factory site on 21 acres, both of which are causing delays. But the LA Times’ Editorial Board says HACLA and city officials must make the Jordan Downs rebuild a priority, and get it built. Here’s a clip:

Numerous challenges lie ahead: There are commitments for some funding but hardly all of it, and the Housing Authority has twice lost out on federal grants for the project. Residents, meanwhile, are fearful of how the rethinking and reconstruction of their homes will change their lives.

The goal of public housing has long been to provide temporary shelter to families who need time to get on their feet before moving on, but Jordan Downs has become a multi-generational village that celebrates together and mourns together. The complex has been the site of both gang warfare and truce.

Questions of ideology and pragmatism lurk in the background. Has traditional public housing failed? Will adding market-rate housing and retail better serve the people who live there? Will the new Jordan Downs be an alternative to old-style projects such as Nickerson Gardens, Imperial Courts and Gonzaque Village, or a model for them?

However those questions are answered, it’s crucial for current and future residents that Jordan Downs be rebuilt into a complex that could offer a way out of subsidized housing and up the economic ladder.

[SNIP]

Plans for the new development have it maintaining 700 units of subsidized housing, and every resident in good standing at the old Jordan Downs is being promised a home there. An additional 700 units of market-rate and affordable housing would also be built. Ideally, subsidized residents would get jobs and earn more income and graduate to nonsubsidized housing, possibly in the same complex. The retail complex would also offer job opportunities for residents in Jordan Downs and throughout Watts.

But first, it has to get built.

AMERICA’S DISEASED BAIL SYSTEM AND PRE-TRIAL DETENTION

The NY Times’ Nick Pinto takes a hard look at bail,the punishment-until-proven-innocent system that disproportionately affects the poor and keeps jails and prisons overflowing.

More than half of the nearly 750,000 people locked in city and county jails nationwide have not been convicted of a crime. And many of them remain in jail awaiting trial because can’t pay the bail amount a judge has set, not because they are a threat to public safety or in danger of absconding.

Time spent in jail pretrial, solely because a poor person gets arrested and can’t afford bail, can be extremely counterproductive for all concerned, causing loss of the person’s job, removing a parent from his or her family unnecessarily, and contributing to the cycle of incarceration that keeps jails and prisons stuffed.

The broken bail system also pressures people to take plea deals they might otherwise refuse, so as not to have to spend weeks, months, or years, behind bars without a conviction. Sometimes, like in the case of Sandra Brown (link), victims of the bail system don’t even make it out alive.

In the case of Kalief Browder, an inability to post $3,000 bail led to a three-year stint at Rikers Island, most of which was spent in solitary confinement. Browder came out of Rikers and isolation and struggled for three years with mental illness and the aftereffects of prolonged solitary confinement. Browder tried to kill himself several times, finally succeeding in June of this year. He was 22-years-old.

Here’s how Pinto’s story opens:

On the morning of Nov. 20 last year, Tyrone Tomlin sat in the cage of one of the Brooklyn criminal courthouse’s interview rooms, a bare white cinder-block cell about the size of an office cubicle. Hardly visible through the heavy steel screen in front of him was Alison Stocking, the public defender who had just been assigned to his case. Tomlin, exhausted and frustrated, was trying to explain how he came to be arrested the afternoon before. It wasn’t entirely clear to Tomlin himself. Still in his work clothes, his boots encrusted with concrete dust, he recounted what had happened.

The previous afternoon, he was heading home from a construction job. Tomlin had served two short stints in prison on felony convictions for auto theft and selling drugs in the late ’80s and mid-’90s, but even now, grizzled with white stubble and looking older than his 53 years, he found it hard to land steady work and relied on temporary construction gigs to get by. Around the corner from his home in Crown Heights, the Brooklyn neighborhood where Tomlin has lived his entire life, he ran into some friends near the corner of Schenectady and Lincoln Avenues outside the FM Brothers Discount store, its stock of buckets, mops, backpacks and toilet paper overflowing onto the sidewalk. As he and his friends caught up, two plainclothes officers from the New York Police Department’s Brooklyn North narcotics squad, recognizable by the badges on their belts and their bulletproof vests, paused outside the store. At the time, Tomlin thought nothing of it. ‘‘I’m not doing anything wrong,’’ he remembers thinking. ‘‘We’re just talking.’’

Tomlin broke off to go inside the store and buy a soda. The clerk wrapped it in a paper bag and handed him a straw. Back outside, as the conversation wound down, one of the officers called the men over. He asked one of Tomlin’s friends if he was carrying anything he shouldn’t; he frisked him. Then he turned to Tomlin, who was holding his bagged soda and straw. ‘‘He thought it was a beer,’’ Tomlin guesses. ‘‘He opens the bag up, it was a soda. He says, ‘What you got in the other hand?’ I says, ‘I got a straw that I’m about to use for the soda.’ ’’ The officer asked Tomlin if he had anything on him that he shouldn’t. ‘‘I says, ‘No, you can check me, I don’t have nothing on me.’ He checks me. He’s going all through my socks and everything.’’ The next thing Tomlin knew, he says, he was getting handcuffed. ‘‘I said, ‘Officer, what am I getting locked up for?’ He says, ‘Drug paraphernalia.’ I says, ‘Drug paraphernalia?’ He opens up his hand and shows me the straw.”

Stocking, an attorney with Brooklyn Defender Services, a public-defense office that represents 45,000 indigent clients a year, had picked up Tomlin’s case file a few minutes before interviewing him. The folder was fat, always a bad sign to a public defender. The documentation submitted by the arresting officer explained that his training and experience told him that plastic straws are “a commonly used method of packaging heroin residue.” The rest of the file contained Tomlin’s criminal history, which included 41 convictions, all of them, save the two decades-old felonies, for low-level nonviolent misdemeanors — crimes of poverty like shoplifting food from the corner store. With a record like that, Stocking told her client, the district attorney’s office would most likely ask the judge to set bail, and there was a good chance that the judge would do it. If Tomlin couldn’t come up with the money, he’d go to jail until his case was resolved.

Their conversation didn’t last long. On average, a couple of hundred cases pass through Brooklyn’s arraignment courtrooms every day, and the public defenders who handle the overwhelming majority of those cases rarely get to spend more than 10 minutes with each client before the defendant is called into court for arraignment. Before leaving, Stocking relayed what the assistant district attorney told her a few minutes earlier: The prosecution was prepared to offer Tomlin a deal. Plead guilty to a misdemeanor charge of criminal possession of a controlled substance, serve 30 days on Rikers and be done with it. Tomlin said he wasn’t interested. A guilty plea would only add to his record and compound the penalties if he were arrested again. ‘‘They’re mistaken,’’ he told Stocking. ‘‘It’s a regular straw!’’ When the straw was tested by the police evidence lab, he assured her, it would show that he was telling the truth. In the meantime, there was no way he was pleading guilty to anything.

When it was Tomlin’s turn in front of the judge, events unfolded as predicted: The assistant district attorney handling the case offered him 30 days for a guilty plea. After he refused, the A.D.A. asked for bail. The judge agreed, setting it at $1,500. Tomlin, living paycheck to paycheck, had nothing like that kind of money. ‘‘If it had been $100, I might have been able to get that,’’ he said afterward. As it was, less than 24 hours after getting off work, Tomlin was on a bus to Rikers Island, New York’s notorious jail complex, where his situation was about to get a lot worse.

But the bail system wasn’t always this way.

When the concept first took shape in England during the Middle Ages, it was emancipatory. Rather than detaining people indefinitely without trial, magistrates were required to let defendants go free before seeing a judge, guaranteeing their return to court with a bond. If the defendant failed to return, he would forfeit the amount of the bond. The bond might be secured — that is, with some or all of the amount of the bond paid in advance and returned at the end of the trial — or it might not. In 1689, the English Bill of Rights outlawed the widespread practice of keeping defendants in jail by setting deliberately unaffordable bail, declaring that ‘‘excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed.’’ The same language was adopted word for word a century later in the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Looks like no one is interested in expanding public housing in intercity L.A.(ie Jordan Downs). Building new units at market value with restaurants and shops sounds more like old fashioned profit seeking than old fashioned public housing. Fact is the real estate is too valuable to leave to state dependents ,like welfare moms and G.R. Recipients, their future lies in section 8 vouchers in the high desert area. Looks like over educated liberal white ladies who like to hang out in the “complex and vibrant culture” , study gangs, and practice social work skills are going to have to start commuting, or find a new hobby.

Lol, Nicobar, u wipe ur feet when u leave the house, doncha?

Philistine.. Funny ,when I read your post I swear I could hear you sucking your teeth.

Of course the judge at Tyrone Tomlin’s arraignment hearing aquiesced to the Asst.D.A.’s request to set bail for $1,500. Neither Tomlin or his Public Defender proposed any alternative for consideration by the judge.

Tomlin’s own file and history form the basis of a reasonable request to the judge to grant defendant a release in exchange for his promise to appear at the date set for his next hearing.

Tomlin has lived his entire life in Crown Heights, Brooklyn – there is no expectation that he will change course to abscond on account of this current minor paraphanelia charge. Tomlin’s record indicates a proclivity to plead guilty to past charges and complete the given sentence. As long as his record shows no current bench warrants or egregious unexplained past Failure to Appear, Tyrone Tomlin is an ideal candidate for release on his own recognizance pending trial.

Why his Public Defender failed to present and advocate for this request, has not been explained.

[…] 2000 to 2011, 25 people were killed in the complex. In 2006 alone, Jordan Downs experienced 19 gang-related shootings and seven deaths. The housing […]

[…] 2000 to 2011, 25 people were killed in the complex. In 2006 alone, Jordan Downs experienced 19 gang-related shootings and seven deaths. The housing […]

[…] 2000 to 2011, 25 people were killed in the complex. In 2006 alone, Jordan Downs experienced 19 gang-related shootings and seven deaths. The housing […]