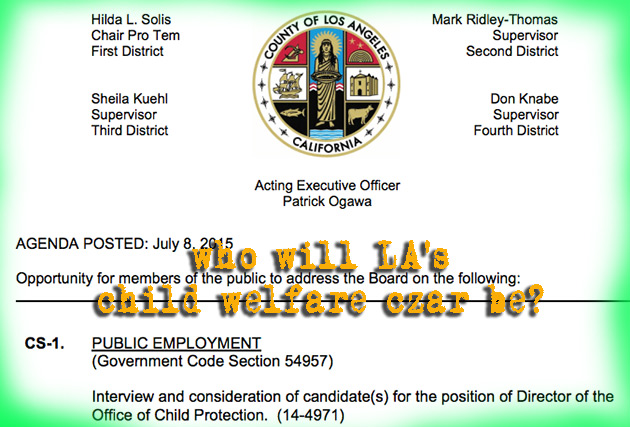

LA COUNTY SUPERVISORS MAY NAME A CHILD WELFARE CZAR TODAY

The LA County Board of Supervisors held a closed-door meeting Tuesday to interview two candidates to lead the Office of Child Protection, an entity recommended by a Blue Ribbon Commission on Child Protection convened to jumpstart much-needed reform efforts in the county child welfare system.

The Supes are slated to interview two more candidates today (Thursday), and could possibly issue their final decision today, as well.

Fesia Davenport, who has served as the interim child welfare czar, is reportedly among those being considered for the position.

Holden Slattery has more on the issue in a story for the Chronicle of Social Change. Here’s a clip:

Fesia Davenport, who the board appointed as interim director of the office in February, is a candidate for the position, according to Wendy Garen, president and CEO of the Ralph Parsons Foundation, which was one of 17 foundations to endorse the BRC recommendations in a letter to the Board of Supervisors.

“It’s been a robust process. There are outside candidates,” Garen said. “I do believe that Fesia [Davenport] is a candidate and that her performance to date has been remarkable.”

Garen said she has no knowledge about the other candidates and, due to that, she does not know whether Davenport is the best candidate for the job.

The creation of an Office of Child Protection was the most prominent recommendation to emerge from the Los Angeles County Blue Ribbon on Child Protection’s (BRC) December 2013 interim recommendations and again in its final report in April.

“I hope that the OCP director who the board ultimately hires is a person that is imbued with many of the traits that the child protection commission envisioned initially,” Leslie Gilbert-Lurie, co-chair of the transition team tasked with implementing the BRC recommendations, said in a phone interview Tuesday. “A strong leader with experience in child welfare who is collaborative and imaginative, and not afraid to stand up to the existing institutions.”

TO CHANGE “CHALLENGING” KIDS’ BEHAVIOR – DONT: PUNISH AND REWARD; DO: HELP KIDS UNDERSTAND AND LEARN FROM THEIR ACTIONS

Katherine Reynolds Lewis has an excellent longread for the July/August issue of Mother Jones Magazine about psychologist Ross Greene’s game-changing discipline methods of teaching kids problem-solving skills instead of employing the now largely discredited punishment-reward system developed by B.F. Skinner in the mid-20th century.

The idea is that, punishing children who are acting out, and who are often called “challenging,” only exacerbates kids’ underlying problems and helps to push them through the school-to-prison pipeline. Kids brains have not developed enough to have control over their behavior and emotions, so punishing them, instead of helping them understand the “why” behind their behavior, is extremely counterproductive, according to Greene’s theory.

Here are some clips:

…consequences have consequences. Contemporary psychological studies suggest that, far from resolving children’s behavior problems, these standard disciplinary methods often exacerbate them. They sacrifice long-term goals (student behavior improving for good) for short-term gain—momentary peace in the classroom.

University of Rochester psychologist Ed Deci, for example, found that teachers who aim to control students’ behavior—rather than helping them control it themselves—undermine the very elements that are essential for motivation: autonomy, a sense of competence, and a capacity to relate to others. This, in turn, means they have a harder time learning self-control, an essential skill for long-term success. Stanford University’s Carol Dweck, a developmental and social psychologist, has demonstrated that even rewards—gold stars and the like—can erode children’s motivation and performance by shifting the focus to what the teacher thinks, rather than the intrinsic rewards of learning.

In a 2011 study that tracked nearly 1 million schoolchildren over six years, researchers at Texas A&M University found that kids suspended or expelled for minor offenses—from small-time scuffles to using phones or making out—were three times as likely as their peers to have contact with the juvenile justice system within a year of the punishment. (Black kids were 31 percent more likely than white or Latino kids to be punished for similar rule violations.) Kids with diagnosed behavior problems such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and reactive attachment disorder—in which very young children, often as a result of trauma, are unable to relate appropriately to others—were the most likely to be disciplined.

Which begs the question: Does it make sense to impose the harshest treatments on the most challenging kids? And are we treating chronically misbehaving children as though they don’t want to behave, when in many cases they simply can’t?

That might sound like the kind of question your mom dismissed as making excuses. But it’s actually at the core of some remarkable research that is starting to revolutionize discipline from juvenile jails to elementary schools. Psychologist Ross Greene, who has taught at Harvard and Virginia Tech, has developed a near cult following among parents and educators who deal with challenging children. What Richard Ferber’s sleep-training method meant to parents desperate for an easy bedtime, Greene’s disciplinary method has been for parents of kids with behavior problems, who often pass around copies of his books, The Explosive Child and Lost at School, as though they were holy writ.

His model was honed in children’s psychiatric clinics and battle-tested in state juvenile facilities, and in 2006 it formally made its way into a smattering of public and private schools. The results thus far have been dramatic, with schools reporting drops as great as 80 percent in disciplinary referrals, suspensions, and incidents of peer aggression. “We know if we keep doing what isn’t working for those kids, we lose them,” Greene told me. “Eventually there’s this whole population of kids we refer to as overcorrected, overdirected, and overpunished. Anyone who works with kids who are behaviorally challenging knows these kids: They’ve habituated to punishment.”

Under Greene’s philosophy, you’d no more punish a child for yelling out in class or jumping out of his seat repeatedly than you would if he bombed a spelling test. You’d talk with the kid to figure out the reasons for the outburst (was he worried he would forget what he wanted to say?), then brainstorm alternative strategies for the next time he felt that way. The goal is to get to the root of the problem, not to discipline a kid for the way his brain is wired.

“This approach really captures a couple of the main themes that are appearing in the literature with increasing frequency,” says Russell Skiba, a psychology professor and director of the Equity Project at Indiana University. He explains that focusing on problem solving instead of punishment is now seen as key to successful discipline.

If Greene’s approach is correct, then the educators who continue to argue over the appropriate balance of incentives and consequences may be debating the wrong thing entirely. After all, what good does it do to punish a child who literally hasn’t yet acquired the brain functions required to control his behavior?

Schools and juvenile detention centers are starting to pick up Greene’s methods and are experiencing complete behavior turnarounds:

In 2004, a psychologist from Long Creek Youth Development Center, a correctional center in South Portland, Maine, attended one of Greene’s workshops in Portland and got his bosses to let him try CPS. Rodney Bouffard, then superintendent at the facility, remembers that some guards resisted at first, complaining about “that G-D-hugs-and-kisses approach.” It wasn’t hard to see why: Instead of restraining and isolating a kid who, say, flipped over a desk, staffers were now expected to talk with him about his frustrations. The staff began to ignore curses dropped in a classroom and would speak to the kid later, in private, so as not to challenge him in front of his peers.

But remarkably, the relationships changed. Kids began to see the staff as their allies, and the staff no longer felt like their adversaries. The violent outbursts waned. There were fewer disciplinary write-ups and fewer injuries to kids or staff. And once they got out, the kids were far better at not getting locked up again: Long Creek’s one-year recidivism rate plummeted from 75 percent in 1999 to 33 percent in 2012. “The senior staff that resisted us the most,” Bouffard told me, “would come back to me and say, ‘I wish we had done this sooner. I don’t have the bruises, my muscles aren’t strained from wrestling, and I really feel I accomplished something.'”

PERSISTING WHITE SUPREMACY IN CA STATE PRISONS…AND DYLAN ROOF

In an essay for the Marshall Project, James Kilgore, who spent the majority of a six-and-a-half year prison term in California facilities, considers how Charleston church shooter Dylan Roof might be received at a CA prison where inmates have been racially segregated for decades.

Kilgore calls for national dialogue on white supremacy in prisons and urges lawmakers and corrections officials to put an end to their “complicity in reproducing hatred and division” through racially segregated detention facilities.

Here’s a clip:

He would certainly find instant camaraderie with the Peckerwoods, the Skinheads, the Dirty White Boys, the Nazi Low Riders. His admirers, men with handles like Bullet, Beast, Pitbull, and Ghost, would vow to live up to Roof’s example, either by wreaking havoc when they hit the streets or maybe even the very next day in the yard.

Roof’s newfound fan club would be ready to provide him with prison perks — extra Top Ramen, jars of coffee, a bar of Irish Spring. The guards, many with their own Roofish sympathies, would cut him some slack — an extra roll of toilet paper here, a few illicit minutes on the telephone there. If Roof were so inclined, the guards might turn a blind eye to his indulgence in illegal substances, from tobacco to papers of heroin to the carceral Mad Dog 20/20 known as “pruno.”

If Roof played by the convict code, he might quickly rise in the ranks of the white-power structure in the prison yard. Maybe after a few years, he would earn the status of “shot caller,” the highest rank within the racial groups. Then he could order hits on young white boys who defiled the race by playing a game of chess with a black man or offering a Latino a sip of his soda. Like all his white comrades, Roof would use the white showers, the white phones, the white pull-up bars. The yard might spark visions of a segregated utopia for Dylann, a wonderland where everyone was in their right place — separate and unequal.

But white supremacists in prison also live in a world of racial enemies. Fueled by paranoia and buttressed by complicit guards and administrators, Roof would be the target of personalized vengeance attacks. Just like on the streets, he would be constantly looking over his shoulder to fend off real and imagined enemies. In particular, he would realize that in a prison yard, there are plenty of black lifers who have nothing to lose and the muscle power to break him in half, like a dry stick. A warrior who took down Roof would get a hero’s welcome in the torturous isolation blocks at Pelican Bay or Corcoran. All this tension would no doubt make Roof a little uneasy, perhaps force him to remain “suited and booted,” armed with a razor blade in his mouth or a sharpened shank up his rectum.

But even with danger all around him, Roof might find solace in the fact that the prison authorities would not assign any whites and blacks to share a cell and would enable the segregation of day rooms and exercise spaces. This would be a refreshing change of pace for Roof.

WHY WAS POMONA TEEN ACCUSED OF ROBBERY FOUND BLUDGEONED TO DEATH IN HIS CELL, FAMILY ASKS

The parents of a 19-year-old robbery suspect, Rashad Davis, fatally beaten in his jail cell in May, want answers from the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department about why their son was assigned to a cell shared by a mentally unstable cellmate accused of beating a man to death with a baseball bat.

The SB Sheriff’s Dept. has not indicated whether or not Davis was housed with 22-year-old Jeremiah Ajani Bell due to a breakdown in screening protocol, but the department has recently been the subject of several scandals and investigations, including alleged excessive use of force and inadequate mental health treatment for inmates.

The LA Times’ Paloma Esquivel has the story. Here’s a clip: