For the the last quarter century, the overrepresentation of Black Americans in the nation’s justice system has been well-documented.

Now a new series of reports outlines the racial disparities that still define the nation’s juvenile justice system, including where that system intersects with U.S. child welfare system.

The three new reports, which were just released by The Sentencing Project, detail the scope of the problem, that in some states has gotten dishearteningly worse in recent years, while in a few other states there has been gradual improvement.

Black kids and unequal justice

Despite the fact that, for some time now, youth arrests and youth detention have been on a downward trajectory, both nationally and locally, damaging racial disparities remain, although the details of the disproportionate numbers differ somewhat between Black, Tribal and Latinx kids.

The first of the three reports outlines the situation facing Black youth, who are more than four times as likely to be detained or committed in juvenile facilities as their white peers, according to nationwide data collected in October 2019, which has just now been released.

In 2015, the incarceration rate for Black youth was five times as high as that of their white peers, which was “an all-time peak,” writes Josh Rovner, senior advocacy associate for the Sentencing Project, and the author of the series of reports.

Now, as of October 2019, that ratio has fallen to 4.4 — a 13% decline — for the 36,479 youth held in 1,510 detention centers nationwide, which includes youth prisons, residential treatment centers, and group homes.

(These data do not include the 653 people under 18 in adult prisons at year-end 2019, or the estimated 2,900 people under 18 in adult jails.)

Forty-one percent of the youths in placement are Black, even though Black Americans comprise only 15% of all youth across the United States.

When the report breaks the measures of disproportionality down for individual states, it finds that Black youth are more likely to be in custody than white youth in every state but one: Hawaii.

In New Jersey, however the skewing is unusually high with Black youth more than 17 times as likely to be incarcerated than their white peers.

Nationally, the overall youth placement rate is 114 per 100,000 kids. Of those youth placed, the Black youth placement rate was 315 per 100,000, compared to the white youth placement rate of 72 per 100,000.

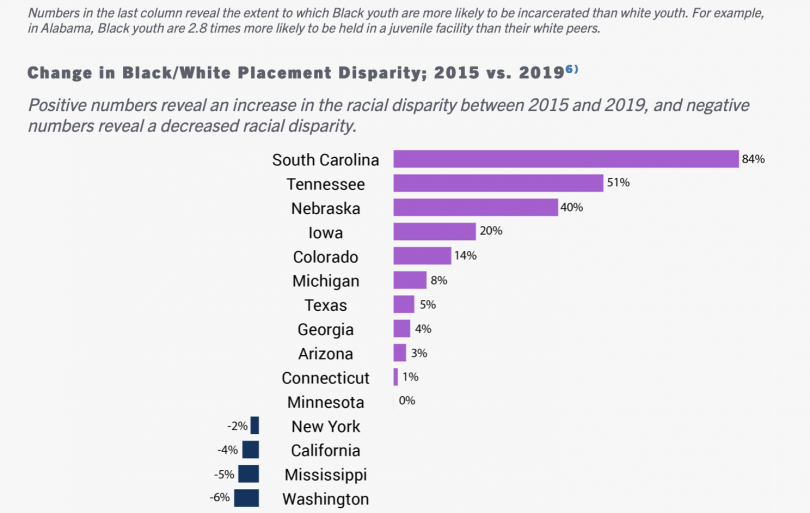

Since 2015, racial disparities grew by more than 10% in 11 states and decreased by at least 10% in 23 states and the District of Columbia.

(To see the numbers on Black disparities in youth incarceration for all 50 states check out the charts here.)

Things grow worse for Indigenous kids

Like Black youth, Indigenous youth are subject troubling disparities that in many states are worse than those of Black children.

According to the new set of reports, tribal kids are more than three times as likely to be detained or committed in juvenile facilities as their white peers.

Yet, while the ratio has come down slightly for Black youth, it has gone up for Tribal youth, according to the reports.

When it comes to youth placement — which includes residential treatment centers, group homes, in addition to youth justice facilities — for Tribal youth the numbers are depressingly skewed.

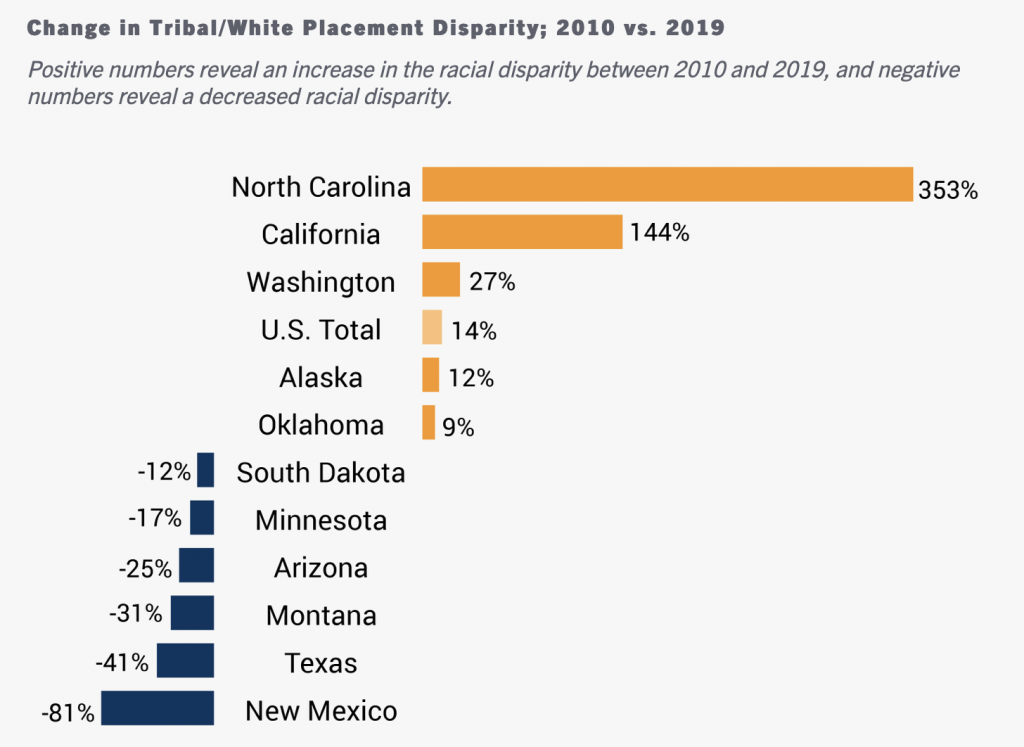

Between 2010 and 2019, juvenile placements in the U.S., over all fell by 48%. During these same years, however, white youth placements declined faster than Tribal youth placements (48% vs. 39%), “resulting in the growth of an already significant disparity,” according to Rovner.

Nationally, the new reports show the youth placement rate to be 114 per 100,000. For Tribal youth, the placement rate is 236 per 100,000, compared to the white youth placement rate of 72 per 100,000.

In sum, in 2010, Tribal youth’s incarceration rate was 2.9 times higher than their white peers. In 2019, that ratio grew to 3.3 times higher, a 14% increase.

As is true for Black youth, for Tribal youth, in some states the disparities are far worse than others.

The report on Tribal youth looks at 11 U.S. states, which have at least 8,000 tribal youths or more in their population. In nine of those 11 states, Tribal youth are more likely to be in custody than white youth. Yet, in Texas and New Mexico stats have improved until the stats are close to even, and the disparities have almost vanished. And in a third stay, Montana, while the disparities for Tribal kids have not disappeared, they have narrowed, and continue to drop.

At the other end of the scale, when it comes to North Carolina and our own state of California, in particular, the racial disparity for Tribal youth has more than doubled.

Latinx youth see some improvement, but still face unequal justice

While the disparities for Latinx youth are, generally not as extreme as those for Black and Tribal youth, Latinx kids are still 28% more likely to be detained or committed in juvenile facilities than their white peers, according to the third of the newly-released reports.

In 2011, Latinx youth’s incarceration rate was a horrifying 80% higher than their white youth peers, a rate roughly equivalent to the preceding 10 years. The disparity gradually fell in the years of 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019.

Now, though still disturbing, the Latinx-white youth placement disparity “has dropped by roughly one-third since 2011,” according to Rovner.

As is the case for Black kids and Tribal kids, the disparity varies from state to state.

Across the 42 states that are home to at least 8,000 Latinx youths, in 31 states Latinx youth are more likely to be in custody than white youth, but in 11 states, interestingly they are less likely.

To put the numbers another way, disparities grew by more than 10% in 13 states and decreased by at least 10% in 22 states.

- In five states, Latinx youth are at least 50% more likely to be held in placement as are white youth: Maryland, Washington state, Virginia, Texas, and Tennessee.

- Mississippi and Minnesota have seen their disparity grow by at least one-fifth.

- Five states decreased their racial disparity by at least half: New Mexico, Missouri, Florida, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.

In short, there’s a lot more to the Sentencing Project’s three new reports, which we encourage you to check out in detail.

And, while you’re at it, we recommend you take a look at this new op-ed in the Washington Post that looks at how and why mass incarceration is not just bad law enforcement policy. It’s bad for the economy, too.

Plus, now that you’re on a roll, and since it’s a critical parallel topic, also take a look at this story by Priya Krishnakumar at CNN about “how crime stats lie — and what you need to know to understand them.“