Pathways to permanent housing

California lawmakers are currently considering a handful of bills that aim to improve outcomes for formerly incarcerated people by removing some of the most pressing “collateral consequences” of criminal convictions – rules that keep people from accessing housing, employment, and other necessities.

Reports from the Prison Policy Initiative have revealed troubling statistics of reentry after prison.

One 2018 report showed that, in 2008, approximately 27 percent of formerly incarcerated people were looking for a job, but were still unemployed, a rate higher even than the general U.S. unemployment rate of 24.9 percent during the Great Depression. Yet people who had spent time in prison were also more likely to be actively seeking employment than the general population.

Another national study from PPI showed that formerly incarcerated people were nearly 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public.

Two bills would widen the pathway to housing for people caught in a cycle of homelessness and incarceration.

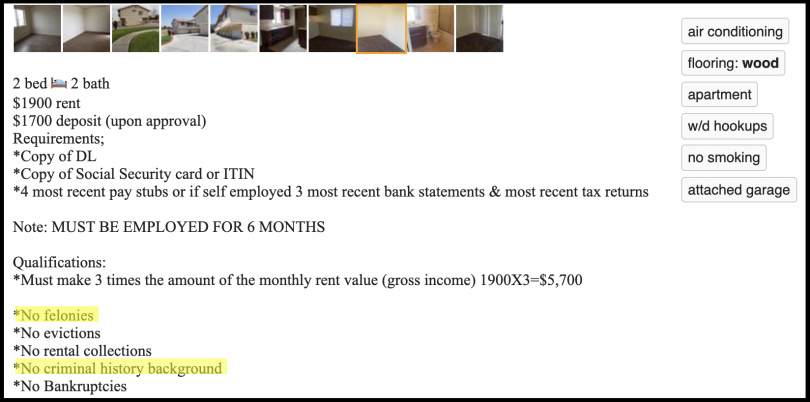

The first bill, AB 2383, by Assemblymember Reggie Jones-Sawyer (D-Los Angeles), would prohibit landlords from seeking criminal history information from applicants during the first stage of the housing application process.

Background checks would also only be able to access information from the last seven years.

If a landlord, after conducting a background check during the secondary phase of screening, intended to deny an applicant based on their criminal history, the landlord would also have to provide the applicant with a written explanation for the potential denial within five days.

The potential renter would then have three days to give the landlord a letter either disputing the criminal history information or providing evidence of rehabilitation or other mitigating information. Then, the owner would be required to reconsider the applicant.

These rules do not apply, however, to owners renting out rooms, guest houses, or other housing on property where they — the landlords — reside.

AB 2383 is backed by the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, the Los Angeles Regional Reentry Partnership, and the Young Women’s Freedom Center.

The bill has faced opposition from the California Association of Realtors, who argue that enacting the bill will endanger tenants who live in the complexes and properties formerly incarcerated people are applying to rent.

Yet, a coalition of justice reform groups, including All of Us or None, which seek to increase housing opportunities for formerly incarcerated people, oppose the bill in its current form for far different reasons. These opponents say landlords should be required to offer a conditional offer to an applicant before they can run a criminal background check.

“Without a conditional offer, there is no way to prove that the applicant otherwise met the landlord’s criteria for credit and tenant history,” the coalition argued. The advocates also point out that three days is not enough time for rental applicants to come up with rebuttals and supporting documents.

As of April 5, 2022, the bill was before the Assembly Judiciary Committee.

A second bill, AB-1816, from Assms. Isaac Bryan (D-Los Angeles) and Ash Kalra (D-San Jose), seeks to directly address the issues that allow people leaving prison to slip into homelessness.

The bill would create a state-level Reentry Housing and Workforce Development Program. This program would offer “five-year renewable grants to counties, continuums of care and community-based organizations to fund evidence-based housing and housing-based services and employment interventions to allow people with recent histories of incarceration to exit homelessness and remain stably housed.”

The money would fund long-term rental assistance, landlord incentives, including security deposits and holding fees, and more.

“Recent data indicates it costs CDCR nearly $100,000 per inmate per year to incarcerate someone in a California prison,” the Assembly Fiscal Committee’s summary of the bill noted. “A chronically homeless person living unsheltered costs tax payers an average of $36,000 per year. The cost to provide permanent supportive housing, affordable housing coupled with services, costs an average of $20,000 per person per year and reduces the risk of recidivism sevenfold.”

AB 1816 was revised and sent to the Assembly Committee on Appropriations on March 24, 2022.

Access to expungement

Bills focused on expanding access to criminal record expungement are also moving through the legislative committees.

One notable bill authored by Senator Scott Wiener, SB 1106, would ensure that unpaid restitution debt would not preclude an otherwise eligible person from clearing their record.

“A person’s poverty should not block them from having their record cleared,” said Senator Wiener. “We’re forcing formerly incarcerated people into a cycle of debt that helps no one. If we want people to actually pay off their restitution debt, they need to be able to access housing and employment.”

Wiener’s bill passed out of the Senate Public Safety Committee on March 24 and is currently on the Senate floor.

Broadening employment opportunities

Several other promising bills would address barriers to employment that keep formerly incarcerated people struggling to find work.

AB 2425, by Assm. Bryan, would provide stipends equivalent to the minimum wage to help formerly incarcerated Californians pay for their basic needs while they work toward obtaining credentials for “high road” careers in sectors like green-energy, healthcare, construction and infrastructure. Most of these credential programs are full-time, making it difficult for people to participate if they don’t have another source of income.

The aptly named Hire UP: From Corrections to Career Pilot Program would be implemented through 10 community college districts throughout the state.

Another bill, AB 1720, would simplify and shorten the process for formerly incarcerated people to earn licenses through the California Department of Social Services allowing them to work in community care facilities.

AB 1720 is currently before the Assembly Committee on Higher Education.