By Melinda Clemmons

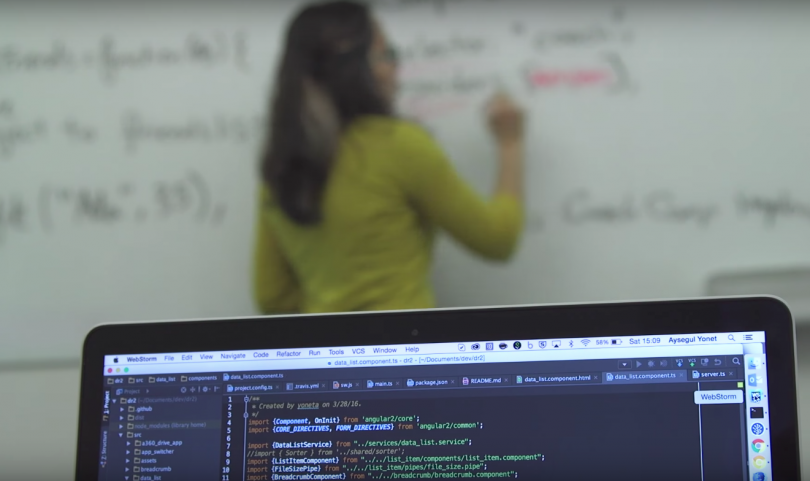

On a recent Tuesday in a brightly lit classroom in the San Francisco Bay Area, a roomful of students began a six-month computer skills course designed to change their lives.

Referred by shelters for survivors of commercial sexual exploitation in San Francisco and nearby Alameda County, the students at a nonprofit called AnnieCannons learn skills from basic digital literacy to coding. They earn income while in the job training program, and then parlay the new skills into careers in the tech industry.

Honoring early astronomer Annie Jump Cannon, the organization’s name connotes “innovation through collaboration, especially collaboration of the under-appreciated,” according to its website.

After serving sex trafficking survivors ages 18 and up for the past three years, AnnieCannons is expanding its program to include minors. The San Francisco Bay Area has been identified by the FBI as one of the nation’s high-intensity areas for commercial sexual exploitation of children, highlighting the need for programs providing pathways out of what is commonly referred to as “the life.”

Here as well as elsewhere in the nation, recent years have seen increased understanding about commercial sexual exploitation (CSE), or trafficking, of minors. An example is the “No Such Thing as a Child Prostitute” campaign, which resulted in the Associated Press changing the language used to refer to victims of child sex trafficking. Not long after, legislation was passed in California to protect exploited minors from arrest, requiring law enforcement to connect them to services rather than locking them up at juvenile hall.

When Executive Director Laura Hackney and co-founder Jessica Hubley launched AnnieCannons a few years ago, they felt that after survivors had reached shelters, too little attention was paid to helping them remain free.

“All of the focus and media attention was on that initial rescue,” Hackney said, “making this distinct binary between slavery and freedom, as if to say, ‘Now that we’ve rescued you, go be free.’”

Seeing that survivors were being offered case management, counseling, legal aid, and other services but only piecemeal job training, if any, the team at AnnieCannons created a program to address one critical aspect of the vulnerability of survivors by creating a path to financial independence.

“We picked technology because it is lucrative, and relatively ‘education agnostic,’” Hackney said. Regardless of their educational backgrounds, after relatively short-term training in the digital field, survivors can earn upwards of $25 an hour doing data entry, with big jumps in earning power with the acquisition of coding and website design skills.

So far, 90 percent of AnnieCannons students have completed “Digital Basics,” the first six weeks of the program, giving them skills with an annual earning potential of $45,000. Four-fifths went on to complete the subsequent “Web Development” phase of the program. Graduates of this second phase can earn up to $80,000 designing websites and doing other web development work.

As described in its business plan, the program partners with large tech companies such as Palantir, which outsources data entry work to AnnieCannons’ separately branded development shop. This arrangement serves both to provide income for the students as well as, eventually, sustainability for AnnieCannons.

Providing an on-ramp to the notoriously non-diverse technology field, AnnieCannons trains many girls and women of color, a disproportionate number of whom are sexually exploited.

“When I hear survivors speak about what they need in their lives, they talk about someone to believe in them and they talk about opportunity,” said Jakki Bedsole, director of programs at Oakland-based MISSSEY (Motivating, Inspiring, Supporting & Serving Sexually Exploited Youth). A nonprofit providing mentoring and other supportive services to youth who have been exploited, MISSSEY refers students to AnnieCannons.

“Survivors aren’t often given opportunities in the tech field,” Bedsole said. “That’s why AnnieCannons is so incredible. It’s creating an option for sustainability and self-sufficiency that’s outside the realm of what’s usually possible.”

Most survivors of exploitation have histories of child abuse or neglect, with many having experienced foster care as a result. The AnnieCannons curriculum was designed to be sensitive to trauma their students have experienced, whether before or during their exploitation, and organizations that refer students continue to provide case management and mentoring throughout the training.

Aiming not only to transform the lives of individuals who have been exploited but also the systems that impact them, AnnieCannons classes develop software to solve problems the students identify as issues they’ve faced in their own lives. TRO Express, created in the AnnieCannons classroom, is an app, now in prototype, designed to help those going through the legal process of getting a restraining order.

Another student project addressed the underreporting of sexual assault with a product that aims to create more awareness as well as bring about policy change. An AnnieCannons board member is serving as the CEO for this product, which will be incubated as its own non-profit.

“This is one of our core goals at AnnieCannons,” executive director Hackney said, “to have students who want to address things like gender-based violence or trafficking in their projects, and build them out into their own companies or nonprofits.”

AnnieCannons initially received pushback on this ambition for their students, according to Hackney.

“People said, ‘Just focus on training people and then find them jobs,’ but we couldn’t just do that,” Hackney said. “For one thing, people need access to income throughout the training but also there are so many barriers for women, women of color, survivors of trafficking to make it in the tech industry.”

“So much of it is building up their confidence,” Hackney said. “We haven’t had a single person come in and say, ‘I know technology is for me.’ It’s been a process of convincing people that this is something they can do.”

MISSSEY’s Bedsole sees the program model as filling a critical need, and is not surprised that providers serving survivors of exploitation across the country have reached out to AnnieCannons with interest in replicating it.

“A lot of services for survivors are responsive to trauma and to ‘something that’s happened,’” she said, “and we should continue to do that but what’s beautiful about an organization like AnnieCannons is it gives folks a career, a sustainable way to leave the life and remain disengaged from exploitation, and that’s what survivors are saying they want and need, and that’s what survivors deserve.”

One AnnieCannons student echoed that thought.

“I think one of the scariest aspects of joining the program was that I had never attempted to do something that I didn’t know that I would be good at. And I had no idea if I would be good at, or even enjoy coding,” said the student, whose name was withheld to protect her privacy.

“Turns out I love it, and I am pretty good at it as well,” she said. “That alone has boosted my confidence to the point where I can now proudly say that I’m in a position where I can provide for my daughter, and truly take pride in myself.”

Melinda Clemmons is a freelance writer and editor who contributes frequently to The Chronicle of Social Change, where this story originally appeared.

Image credit: AnnieCannon