CJCJ REPORT FINDS CA JUVENILE DETENTION CENTERS STILL PLAGUED WITH SAFETY AND MENTAL HEALTH DEFICIENCIES AFTER RELEASE FROM CONSENT DECREE

Just six months after the state Division of Juvenile Justice was released from a 12-year consent decree over violence, gang problems, a spate of suicides, and other major issues in the state’s juvie detention facilities, the DJJ still fails to protect locked-up kids and lacks adequate mental health care services, according to a report from the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ).

Back in 2003, following a wave of media reports that kids held in the DJJ’s three facilities—Ventura Youth Correctional Facility, and the O.H. Close Youth Correctional Facility and N.A. Chaderjian Youth Correctional Facility in Stockton, CA—were experiencing physical and sexual abuse, joining gangs, and committing suicide, the law firm Prison Law Office sued the California Youth Authority (which later became the DJJ). The Alameda County Superior Court of California placed CYA/DJJ under a consent decree requiring the adoption of six remedial plans to improve safety within the facilities, physical and mental health treatment, sex behavior treatment, disabilities services, and education systems.

The Superior Court freed the DJJ from the lawsuit (Farrell v. Kernan) in February of this year, saying that the state had fulfilled most of the reform requirements. But major safety and health care problems persist within the detention centers.

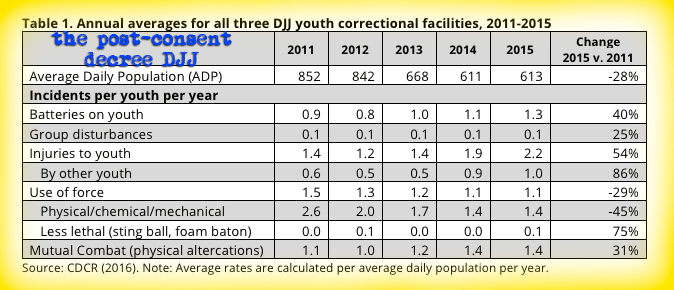

Despite the fact that the daily population in the three DJJ-run facilities has dropped 30% between 2011-2015, youth-on-youth injuries have jumped by 86%. And while there have been fewer uses of more serious force—which the report defines as physical, chemical, and mechanical force—against locked-up kids between from 2011-2015, lesser uses of force—like foam batons and projectile sting-balls—have increased by 75%.

After representing a young defendant locked in a DJJ facility, criminal defense attorney Amy Morton said the DJJ is guilty of “downplaying the reality of the daily violence to which the wards are exposed, and ignoring the environment of fear that permeates the institution.”

Following the end of the consent decree in February, the placement of kids in restrictive units—which greatly reduce out-of-cell time and privileges, and are often employed for punishment purposes when kids’ behavior is deemed “aggressive”—has doubled. Not only are kids being placed in restrictive housing more often, kids in the general population are not receiving the mental health care they need. When a court-appointed mental health care expert shined a light on deficiencies in the mental health care provided to kids in DJJ facilities in 2015, DJJ responded by transferring kids needing “acute” mental health care to adult facilities for treatment.

Another unchecked problem in the state lock-ups—one that was supposed to be solved by the consent decree—is gang influence. In 2012, national youth gang expert Dr. Cheryl Maxson found that the environment within the three facilities led to kids joining gangs “early in their stay,” or becoming even more involved in gangs if they were already affiliated. These problems have persisted beyond the end of the consent decree, CJCJ researchers found: “In failing to heed recommendations from experts and rejecting evidence-based gang intervention strategies, DJJ has allowed gangs to remain powerfully influential.”

The report calls for increased data reporting in order to promote “transparency and escalated monitoring of California’s youth corrections system, especially in the areas of safety and mental health” in the DJJ’s post-consent decree era.