In a new report by the Prison Policy Initiative, research analyst Leah Wang, points to recently released data that show a record high number of deaths of people locked up in jails, a pattern of mortality that is trending toward smaller, rural jails and a growing number of women being held in these jails, most often for low level charges.

“A lack of accountability and acknowledgement of women’s unique disadvantages all but ensures more deaths to come,” writes Wang of the new numbers and what it points beyond itself to suggest.

Leah Wang is a Research Analyst at the Prison Policy Initiative. Prior to joining PPI Wang was an analyst at the Massachusetts Department of Corrections.

The data the PPI is examining is from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), which recently released the 2018 mortality numbers for local jails across the U.S.

(Sadly, government agencies like the BJS often don’t come out with stats of this nature right away. Fortunately the FBI is a little faster at getting data out, or at least they were until the Trump administration slashed big chunks out of the Federal Bureau of investigations yearly Crime Report, which in the past has always been considered the gold standard for tracking such statistics in the United States. But that’s another topic altogether.)

In any case, according to the BJS, nationwide there were 1,120 jail custody deaths reported, or a rate of 154 deaths per 100,000 people in jail, the highest levels since BJS’ began reporting on the topic in 2000.

“The jail population has grown since 2000, of course, but jail deaths have grown more,” writes Wong.

And the numbers are distressing.

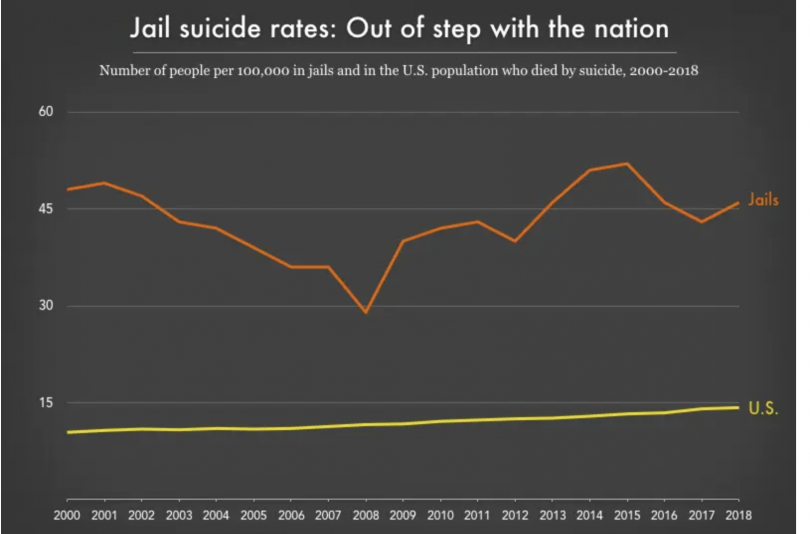

As in past years, suicide was the single leading cause of death for jailed individuals.

In fact inside U.S. jails, almost 30% of deaths are suicides. Furthermore, someone locked up in a U.S. jail is in excess of three times more likely to die from suicide as someone in the general U.S. population.

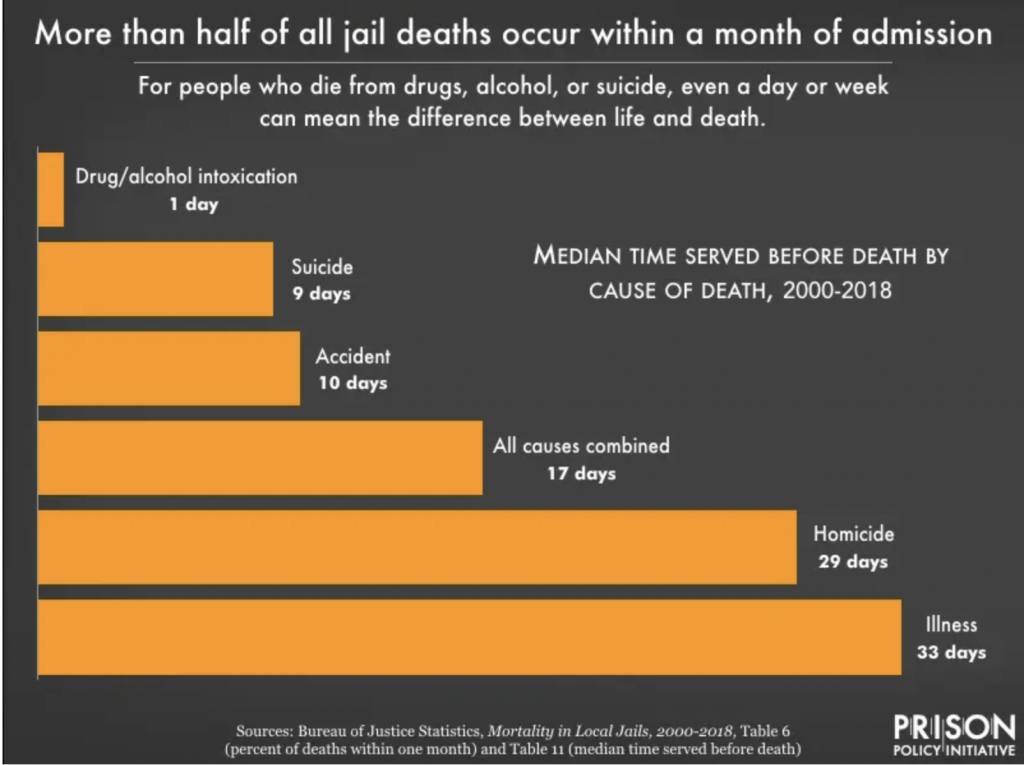

As it happens, most deaths in jail, whether they are by suicide, or drug or alcohol use disorders, or some other cause, tend to happen quickly.

“Millions of people are booked into jails each year with alcohol or drug use disorders, and the number who died of reported intoxication while locked up reached record highs in 2018,” according to the PPI.

Since 2000, when the BJS started collecting data, such deaths are up 381 percent.

Wang writes of one Texas woman, for example, who was jailed for unpaid traffic tickets and died 3 days after her arrest from complications of withdrawal after begging for medical care. Instead, reports Wang, the woman was being told to clean up her own vomit.

Women’s jailing and jail death numbers are on the rise

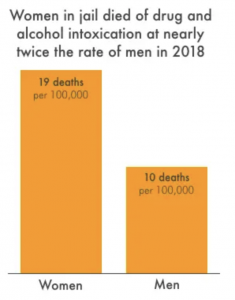

Over the past 35 years, total arrests have risen 25% for women, while decreasing 33% for men, the PPI reported last fall. The jump during that three and a half decade period was largely driven by drug-related arrests, which increased nearly 216% for women, compared to 48% for men

Women also had a 7% higher mortality rate than men in jails in 2018.

Due to the fact that “women are a key driver of jail population growth,” writes Wang, “the rise in their mortality rate should send correctional leaders and policymakers running toward solutions aimed at keeping women out of confinement.”

Well, yes. One would hope.

Instead, for decades, jails in non-urban jurisdictions have “quietly proliferated,” writes PPI’s Wang, noting that the rise in number have been greatly fueled by increases in pretrial detention.

Matters are made worse by the fact that — as a 2021 report found — women entering rural jails are significantly more likely to have co-occurring serious mental illness and some kind of substance use disorder, “despite being severely under-identified by their jails as having such needs.”

Compared to urban women, rural men, and urban men, rural women had significantly higher odds of serious mental illness and co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders, wrote the researchers of the 2021 study.

They also noted that rural woman were nearly 30 times more likely to receive jail-based mental health services. But a discrepancy between screened mental health need and jail-identified mental health need, also showed that, in general, the mental health needs of rural women in the U.S. were severely under-identified compared to their male and/or urban counterparts — all of which points to very real and urgent needs that are well upstream of law breaking, and/or jailing.

Earlier this month, during a discussion about the much talked about spike in violent crime, New York Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez described jails as “garbage bins” for people who are actually suffering from mental health issues.

“The answer,” she said, “is to make sure that we actually build more hospitals, we pay organizers, we get people mental health care and overall health care, employment, etc. It’s to support communities, not throw them away.”

Los Angeles County is, of course, working in that direction. But there is a long way to go.

Los Angeles County jails

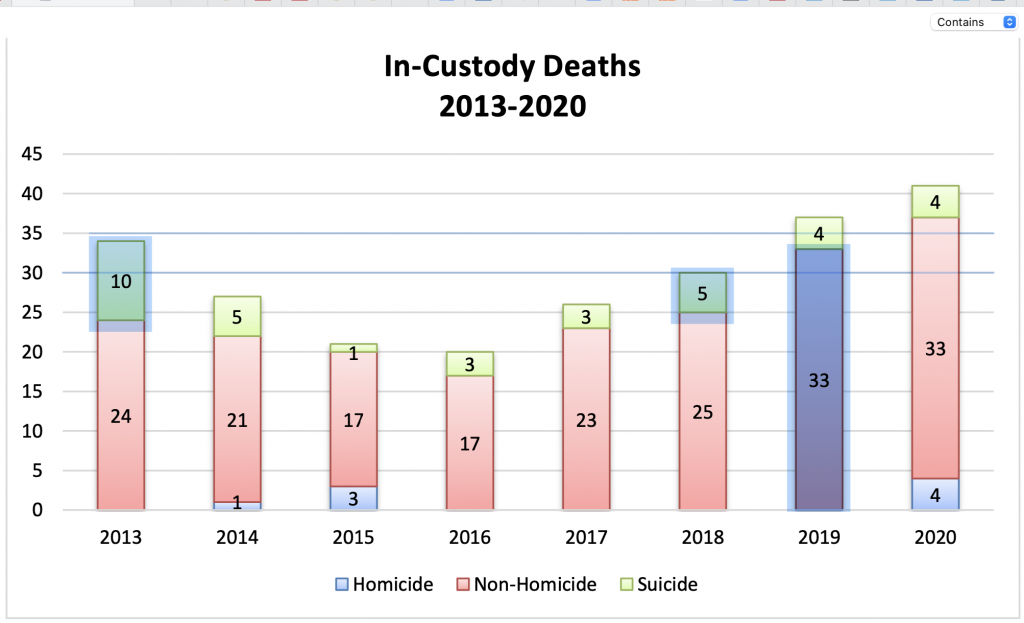

On the topic of jail deaths, back in LA, according to a March 2021 report by Los Angeles County Inspector General Max Huntsman, LA County’s in-custody deaths jumped considerably in the year of 2020 over all other years from 2013 onward. As you can see below, the year of 2019 came the closest to matching the distressing 2020 numbers. )

Graph at top of the page by Prison Police Initiative, based on data from U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.