GOOD SCHOOLS, BAD DISCIPLINE POLICIES

The Long Beach Unified School District (LBUSD) is the third largest school district in California. It manages a budget of over $1 billion and is given the task of molding the minds of a diverse group of almost 78,000 students every year.

LBUSD also has a reputation for being an unusually outstanding school district when it comes to academics.

In 2014, seven of the district’s schools were named for excellence on an annual list released by The Washington Post that ranks the nation’s most challenging high schools. Around that same time, a national nonprofit called Battelle for Kids named LBUSD among five of the world’s highest performing school systems in their Global Education Study.

But, according to a report released this week by the Children’s Defense Fund-California (CDF-CA) and the pro-bono law firm, Public Counsel, this marvelous Long Beach school district may not be, in fact, doing right by all its kids, particularly when it comes to discipline practices and startlingly unequal sets of campus environments.

The authors of the new report—which is titled Untold Stories Behind One of America’s Best Urban School Districts—reviewed hundreds of documents and masses of data acquired through a string of public records act requests, while also delving into anecdotal accounts from students and former students.

At the end of their research, the authors found a pattern of “practices and policies,” which push some Long Beach students out of the classroom more than others, often shoving them, said the authors, toward the school-to-prison pipeline.

Specifically, according to the report’s findings, black and special education students were “disproportionately suspended from school, well beyond the rate of any other subgroup of students.”

Black students were also disproportionately pushed out of comprehensive schools to alternative settings.

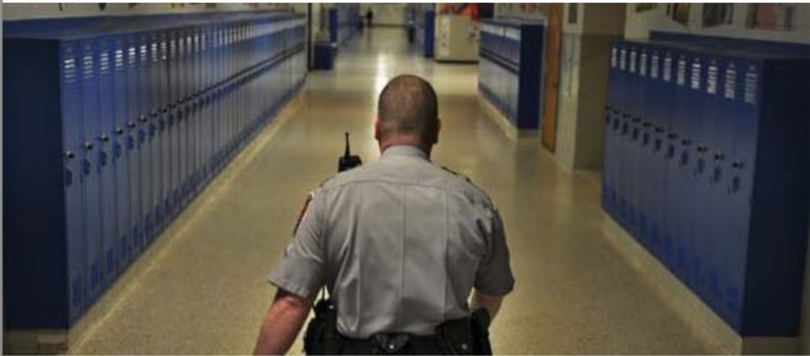

Black and Latino students combined accounted for 86 percent of LBUSD’s student-police contact, despite accounting for 69 percent of LBUSD’s enrollment.

But, when the researchers began to drill down into the data and to the anecdotal accounts by students, they found that the stats weren’t the end of the inequalities when it came to school discipline at LBUSD. Below the surface there was something larger going on.

DIFFERENT SCHOOLS, DIFFERENT RULES

Although it wasn’t evident right away, researchers found that one of the prime causal factors behind these discipline patterns, according to the report, is the fact that LBUSD’s school-based codes of conduct are not created equal from campus to campus. A review of conduct and discipline codes at the high school level showed similarities in rules among some clusters of schools, whereas at other schools, discipline policies were far harsher.

For example, Jordan, McBride, and Lakewood high schools have “the harshest codes of conduct language among LBUSD’s high schools,” according to the report. Jordan High School’s code “forbids 31 behavioral actions and lists out-of-school suspension as a consequence for each of them.”

The so-called suspendable offenses ranged widely—from willful defiance (a category that is no longer used by the LAUSD) profanity, throwing food/littering, and possessing “distracting toys,” to more serious behavior like using/possessing drugs and/or alcohol, assaults on staff, and theft.

Whereas in some LBUSD schools, many of those behaviors triggered counseling or a warning, instead of suspensions, contact with school police, or a transfer to another schools.

These differences in rules, wrote the authors, could not help but send a sub rosa message to students, parents, and community members. “Each school’s code of conduct,” they wrote, “should lead school and district leaders to consider what the codes say about their expectations” of students.

“If we measure what we value, the nature of each school’s code of conduct cannot help but say a great deal about what school and district leaders expect of the students in that school or schools.”

THE ISSUE OF SCHOOL CLIMATE

The report doesn’t merely talk about data. It also focuses on the less quantifiable but critical issue of what education reformers call “school climate,”

School climate is a term that was rising to prominence as an issue, according to the report, during the 2012-13 school year, when many other California districts were working to drastically reduce their suspension and expulsion rates, and the Los Angeles School District, made headlines by doing away altogether with the catch-all disciplinary category of “willful defiance,” that studies showed was often being disastrously misused and overused.

Yet during that same year period, LABSD documented 11,752 suspensions throughout the district, reportedly the highest number of suspensions in Long Beach’s recent history.

As American schools and school districts attempted to reform their punitive discipline strategies that study after study had shown to be unsuccessful when it came to improving behavior, school and district leaders learned that simply changing the rules wasn’t enough. It turned out that a change in “climate,” was also essential.

The U.S. Department of Education put the matter this way:

Teachers and students deserve school environments that are safe, supportive, and conducive to teaching and learning. Creating a supportive school climate—and decreasing suspensions and expulsions—requires close attention to the social, emotional, and behavioral needs of all students.

The the DOE goes on to tell “administrators, educators, students, parents and community members” where on the site they can find “tools, data and resources” to “effectively create positive school climates.”

But while schools all over the country were at attempting to officially institute the kind of road-tested programatic strategies that had been shown to create a healthy and supportive school climate, which in turn produced better outcomes for students, according to the report’s findings, as with Long Beach’s discipline practices, there was no consistent approach to creating a supportive school environment in all the district’s schools.

As a consequence, wrote the authors, “…the absence of a comprehensive document detailing school discipline policies or setting out a clear vision of school climate, results in a patchwork of policies, practices, and inconsistent student treatment.”

The report also noted that the district spent over $35 million on policing students between the 2011–12 and 2014–15 school years, “compared to only $117,112 during the same time period to support its prevention-focused school climate program.”

ACTIVIST STUDENTS REBUFFED

In response to the inconsistent and inequitable discipline and student support that plagued the district, according to the report, a group of Long Beach students launched what they called the Every Student Matters campaign (ESM). The ESM kids were serious and organized enough that they managed to snag support from the Building Healthy Communities initiative, a 10 year, $1 billion community initiative launched by The California Endowment in 2010 that was helping communities advocate for, among other changes, better school climate practices in districts all over California.

But, according to the report, over the past several years, while ESM members and allies attempted dialogue at meetings with LBUSD school board members and the current superintendent, Christopher Steinhauser, “however students have often felt dismissed, ignored, and disrespected” when discussing ESM’s ultimate bottom lines, which were dignity, racial justice, and access to the curriculum.

“Students, parents, and youth-serving organizations are experts in their own experiences and needs,” the report’s authors stated tersely, “and should be able to share in the decision making that impacts them most.” But according to the ESM kids, they repeatedly felt their voices—and their experience-driving perspectives—went unheard.

CALLING FOR DIALOGUE & OPEN DOOR MEETINGS

The 38-page report also featured a list of recommendations, the basics of which were summed up in the author’s statement at the report’s conclusion:

“Exclusionary school climate and culture undermines the district’s mission,” the authors wrote, “and most importantly the academic success and social-emotional health of students. The disparities in the application of school discipline on students of color…and special education students must be acknowledged and addressed with the community, not in a closed session or private meeting that further excludes those most impacted.” Thus they hoped the findings in the report would “spur dialogue about school climate that will help foster curiosity and asset- based solutions.”

The solutions, and the community partners needed “to develop a school climate that protects student rights and dignity, promotes social-emotional wellness and learning, and achieves racial justice are within reach,” the report concluded. “The relationships and recommendations are ready to be nurtured and grown.”