The achievement gap between white students and minority students narrowed by nearly 20 points during the height of school desegregation. In more recent years, however, the fissure has once again widened. During the heyday of No Child Left Behind a plethora of methods were tried to once again narrow the educational disparity affecting so many minority children. But, with certain notable exceptions, in general, most of the strategies failed to consistently produce the needed progress.

A report released last year by the Department of Education noted dourly that, 60 years after Brown v. the Board of Education, the disparity in allocation of educational resources was exacerbating the “achievement and opportunity gap,” rather than remedying it: Black and Latino children are the least likely to be taught by a qualified, experienced teacher, noted Catherine Lhamon, the Assistant Secretary of Civil Rights for the DOE, in a letter. They are also the least likely to get access to AP courses or such college-prep courses as chemistry and calculus, to have gifted and talented programs in their school, or to have access to technology or such education niceties as science labs.

What the Assistant Secretary did not say is that it turns out there is one strategy that has been proven to invariably make the stubborn achievement gap—along with the resource gap—grow smaller. It is, however, a strategy that it is very unfashionable mention—namely school integration.

With this thorny problem in mind, This American Life has produced a a two-part series on education reform that should be mandatory listening. It doesn’t prescribe what we ought to do to improve the minority/white gap in our nation’s schools, but it lays down some interesting facts that bear discussion.

In Part 1, which aired last week, reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones delves into the issue that Lhamon, of the U.S. Department of Education, pointed to unequivocally. “American schools are disturbingly racially segregated, period,” Lhamon said.

in the course of her exploration, Hannah-Jones tells the story of a school district in Missouri, which accidentally ended up integrating—at least for a while. And how it turned out.

In Part 2, which aired this past weekend, producer Chana Joffe-Walt reports on the Hartford, CT, school district, which actively tried to integrate its schools. The challenge was to convince white families that it was to their advantage to go to integrated schools. What happened may surprise you.

The show then follows producer Joffe-Walt as she interviews the Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan on the topic of integration and student achievement.

Both shows are informative, disturbing and hopeful—and loaded with good storytelling.

Don’t miss them.

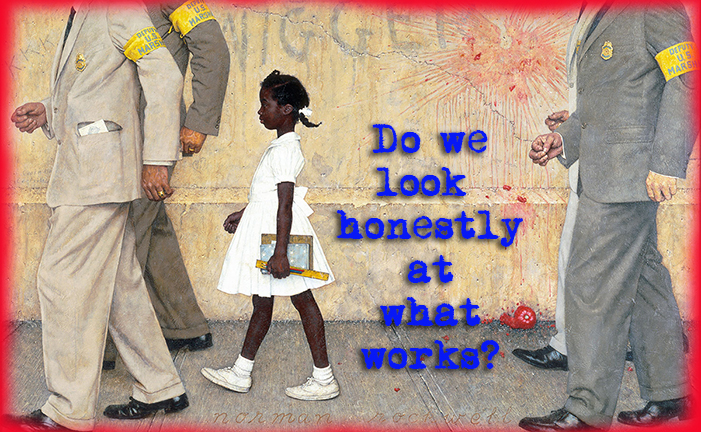

The painting above is, of course, by Norman Rockwell. It is his famous, “The Problem We All Live,” painted in 1964 to depict Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old African-American girl, on her way into an all-white public school in New Orleans on November 14, 1960.

Even Rockwell was clear and “kept it real”. Message

On the other hand, Brother, MLK wasn’t so sure. As Celeste said, the issue is thorny. And here’s a similar take to peruse: The Dark Side of Integration: What Black Kids Learn in a White School System http://blogs.edweek.org/teachers/charting_my_own_course/2015/02/part_two_of_my_black.html