Last year, California legislature passed AB 12, the bill that gives another three years of aid to the young men and women who “mature out” of foster care.

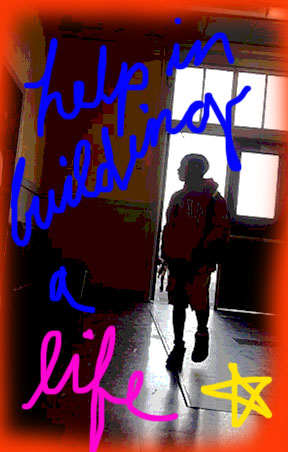

The measure hopes to fix one of the largest problems in California’s foster care system—namely the fact that foster care kids are cut off from nearly all help or support the minute they turn 18. This occurs with very little preparation or help in getting an apartment, a car, a job, health care….and all the other elements of adult life. They are given a few referrals and a bag holding their possessions. That’s it.

As a consequence, sixty-five percent of those who “age out” do so with nowhere to live, and 51 percent are unemployed.

When combined with whatever abuse and/or neglect brought a kid into the system, the effects of this sudden abandonment are stark. One in four former foster kids who matured in the system will be incarcerated within two years of leaving foster care. One in five will become homeless before they turn 20-years old.

Although the bill was passed more than a year ago, AB 12 is not set to kick in until January 1, 2012.

NEW STUDY SHOWS HUMUNGOUS PROBLEMS THAT AB 12 WILL (HOPEFULLY) HELP TO CURE

A unique study focusing on LA County’s Foster Care youth was released last week. Its brand new set of disturbing findings put a spotlight on the fact that the extra three years of help that AB 12 is scheduled to provide is desperately needed—like yesterday.

The research, which was funded by the Conrad Hilton foundation and conducted by University of Pennsylvania professor Dennis Culhane, with help from the LA County CEO’s Office, looked at how well or poorly kids did 3-7 years after exiting foster care and/or LA’s juvenile probation system.

The results were predictably disturbing.

Yet the numbers were by far the grimmest for kids who had been in the possession for both county agencies—the Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) and LA County’s extremely troubled juvenile probation.

The young adults in this double duty group are known as the “crossover” youth.

Among the study’s key findings:

One-third of former foster youth and one-half of crossover youth experienced a period of extreme poverty during their young adult years. For example, a youth exiting the foster care system had cumulative earnings of just under $30,000 over the first four years. The amount of income earned by crossover youth is far more dismal — less than $14,000 over four years.

Of those leaving foster care, 68 percent accessed public welfare benefits during the first four years after leaving the system—costing the County of Los Angeles an average of $12,532.

As for the crossover kids, a staggering 82 percent applied for and collected some kind of public assistance benefits during the first four years after exiting the system—bringing their average total cost to LA County to $35,171 over four years.

The rates of using public welfare declined for both groups in years 5 to 8 but the numbers are still substantial —41 percent for foster youth and 54 percent for crossover youth.

(By the way, this study is the first ever to look at outcomes for crossover youth, those who are involved in both foster care and juvenile justice systems. This is a population of kids that deserves MUCH more focus in the future. )

A HOPEFUL GLIMMER

Both the researchers and foster care advocates were interested to note that almost half of the former foster youth and crossover youth enrolled in community colleges, despite the fact that they were poor, often jobless, in some cases homeless, and often prone to depression and other emotional conditions.

A dispiriting two percent actually received an Associate Degree, but the researchers felt that the willingness to try was significant.

“This study provides compelling evidence that these young adults, especially the crossover youth, should be targeted with housing support, education, employment services and mentoring, if the county and the state are to avoid a lifetime of public dependence by this highly vulnerable population,” said Dr. Culhane. “The good news is that this is a population that can be easily targeted with assistance and that current costs to the county could be potentially offset by reduced incarceration and public assistance costs.”

In other words, when—through AB 12 and related programs—we spend a little bit of extra money and effort on kids transitioning out of foster care, juvenile probation, and those double whammy crossover kids, a lot of money will be saved over these kids’ lifetimes in the way of public assistance and criminal justice costs.

More importantly, the bleak trajectories of these young men and women’s lives can be redirected toward hope and accomplishment.

“..I understood the incredible challenges foster kids faced as they prepared to enter a world that they were not ready for,” said U.S. Representative Karen Bass in a statement released last week. Bass, who was one of the original sponsors for AB 12, said she hopes it will become a model for the county.

And just one more thing to put all this in perspective: A 2007 report indicated that, nationwide, kids who grow up with their own parents typically don’t become self-sufficient until age 26 — and their parents on average contribute $44,000 after they turn 18 in rent, utilities, food, medical care, college tuition, transportation and other necessities to help them get there.

So, yeah, three extra years of a extra help for our County’s kids whom we’ve taken into our collective care is the only sane or wise thing to do.

MEANWHILE….ELSEWHERE IN FOSTER CARE NEWS: WHILE SACRAMENTO DITHERS OVER WHETHER TO OPEN LA COUNTY’S DEPENDENCY COURTS TO MEDIA SCRUTINY, PRESIDING JUDGE MICHAEL NASH SAYS HE WILL DO IT ANYWAY.

Both the LA Times Garett Therolf and the LA Weekly have the story, but Jill Stewart writing for the Weekly, is in a particularly satisfying state of fury about the delays in opening the courts.

By the way, Jill’s anger has mostly to do with abusive parents who get their kids back and do terrible harm to them, whereas I’ve mostly seen the other side, where kids are terribly traumatized when taken from parents unnecessarily.

As Therolf writes of Judge Nash:

“There is a lot that is not good [in the dependency courts], and that’s an understatement,” Nash said earlier this year at a hearing in Sacramento on legislation that would have opened dependency courts. “Too many families do not get reunified … too many children and families languish in the system for far too long. Someone might want to know why this is the case.”

We need sunshine for both sides of this kid-wrecking coin.

AND, FINALLY….MORE ON JAILS:

For those of you following the jails scandal saga (and if you aren’t, why in the world aren’t you?) be sure to read Sunday’s LA Times’ story by Jack Leonard and Robert Faturechi about how jail duty was used to punish certain problem deputies.

NOTE: WE’LL HAVE MORE ON THE JAILS AND THE LASD THIS WEEK