The California Office of Youth and Community Restoration (OYCR) and the Vera Institute of Justice have selected Los Angeles to participate in a multi-year initiative to end the incarceration of girls and gender-expansive youth.

Los Angeles and three other counties — Imperial, Sacramento, and San Diego — have agreed to quickly implement gender-responsive programs and equity-focused policies meant to immediately reduce the number of girls and gender-expansive youth in juvenile halls and camps.

The four counties will receive funding from OYCR and technical guidance from Vera, as they aim for zero.

Vera will help the counties “examine their local data, identify system and programming gaps, and implement policy and programming solutions.” OCYR will give counties $125,00 for reform efforts in the first year. Counties that come up with “bold and effective plans” may receive a subsequent two-year grant of up to $750,000 — $250,000 for probation and other relevant government agencies, and $500,000 for community-based partners.

“These four counties demonstrated a strong commitment towards ending girls’ incarceration and addressing the race and gender disparities in their youth legal systems, and we look forward to partnering with them in this critical effort,” said Lindsay Rosenthal, director of the Initiative to End Girls’ Incarceration at the Vera Institute of Justice.

Progress, but not enough

New data analysis from Vera shows that while incarceration rates are dropping, the statistics regarding who is arrested and sent to juvenile detention — and why — remain bleak.

Black girls represent just 7.8 percent of the state’s youth, but made up 25 percent of admissions to girls’ detention, according to the report, which is called “Getting to Zero: Ending Girls’ Incarceration in California.”

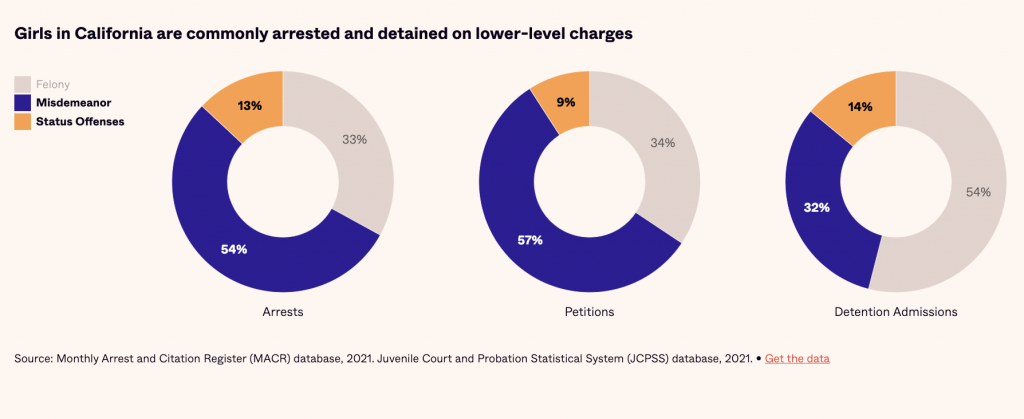

This data also shows that girls and gender-expansive young people are still frequently being locked up for crimes that are only illegal when kids commit them — like violating curfew, skipping school, and running away.

Out of the nearly 4,800 times police in California arrested girls and gender-expansive kids in 2021, 67 percent of the time, kids were accused of misdemeanors and status offenses, according to Vera. Forty-six percent of entries into girls’ lockups were for these non-serious crimes, while 54 percent involved felonies.

Matters are not helped by the fact that these categories of youth are more likely to have experienced involvement with the child welfare system, and other traumatic experiences, including domestic violence, sexual assault, and trafficking, than kids in the general public — usually higher even than incarcerated boys.

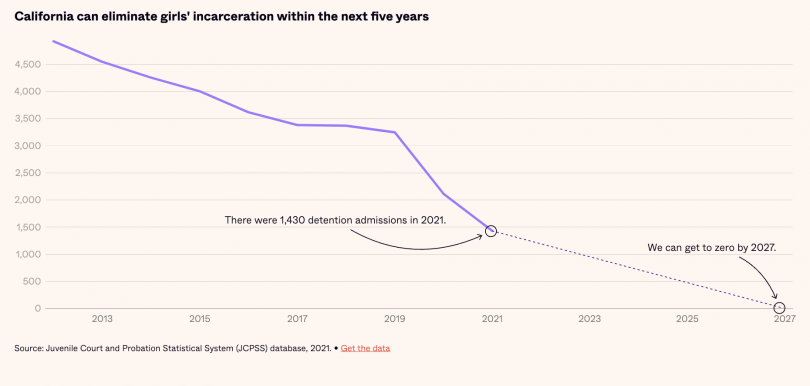

The good news is that, in LA County and across the state, arrests of girls and gender-expansive youth have dropped precipitously over the past decade. In 2012, police in California arrested these youth 33,434 times. In 2018 and 2019 such arrests dropped to between 12,000 and 13,000. By 2021, law enforcement made 4,784 arrests of kids in these categories.

In 2022, LA County held an average of 35 kids in girls’ detention on any given day. In Imperial, Sacramento, and San Diego Counties, the numbers were 2, 14, and 21, respectively.

The assistance from Vera and OCYR, through the collaborative Ending Girls’ Incarceration Action Network, is meant to push the counties over the finish line.

The initiative was born from successful action taken by Santa Clara County, with the help of Vera, to very nearly end the incarceration of girls in the county.

Santa Clara decreased the number of girls sent to juvenile halls and camps by 58 percent from 2018 to 2020, according to Vera.

The initiative did not only benefit kids accused of low-level crimes.

As the organization worked with Santa Clara, they found that most girls charged with felonies received risk assessment scores that recommended against incarceration. In 2018, more than 150 girls were sent to lockup, despite receiving such a risk assessment score. “two-thirds of these girls had underlying felony charges,” Vera explained in the “Getting to Zero” report.

In 2021, Santa Clara’s monthly average number of girls in halls and camps was between zero and one.

“With focused attention and investment, it is possible to end girls’ incarceration statewide by 2027,” according to Vera.

The timing is certainly critical in Los Angeles given that, as WLA has been reporting, the youth side of LA County’s Probation Department is in a state of crisis.

Chaos in the halls

On March 7, the LA County Board of Supervisors fired Probation Chief Adolfo Gonzalez.

On May 2, less than two months later, Gonzalez’s former second-in-command, Karen Fletcher, resigned from her new appointment as the Interim Chief of Probation.

On February 9 2023, just under a month before Chief Gonzalez was fired, the California Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) released a report showing that Los Angeles County Probation’s two main youth lock-ups — Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall and Central Juvenile Hall — were so far out of compliance with the state’s basic standards of care and safety for kids, that the oversight body may be forced to declare the halls “unsuitable for youth habitation.”

Among other violations of state statutes, the BSCC found that probation was keeping kids isolated in their rooms beyond the maximum allowable four hours.. The board found kids were not getting adequate education and rehabilitation services,

(Before his firing, former Chief Gonzalez also told the BSCC that only 11 percent of staff members were showing up for work inside the halls, making adequate programming, including any kind of physical activity, all but impossible.)

The BSCC found that some of the staff members who did show up were locking themselves away from the kids in offices rather than directly supervising. In other cases, staff were not consistently performing safety checks, and when safety checks were performed, the reports didn’t match what happened on video.

The list of 39 areas where the youth halls were out of compliance went on from there.

In March, a little over a month after the February BSCC report, the Chief Probation Officers of California (CPOC) publicly called on state and county officials to put the county’s youth lockups into court receivership.

Problems in the halls and camps go beyond those listed by the BSCC. Traumatized kids are often retraumatized. There are overdoses and violence.

In 2019, when an incarcerated teen reported that a probation officer had sexually assaulted her on multiple occasions over several months between 2018 and 2019, at the county’s now-shuttered Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall, probation leaders moved the teen to a group home, while leaving the accused officer in a position of power over minors. When the girl again told a mandated reporter about the reports, explaining that the same man was still contacting her over social media, the probation department continued to do very little to investigate the issue.

Then, in 2022, nearly 300 people joined a class action lawsuit alleging that they experienced sexual assault while held in LA County’s lockups as minors between the years of 1972 and 2018.

Additionally, despite multiple motions from the LA County Board of Supervisors between 2019 and 2022 directing the Probation Department to phase out use of the chemical agent in juvenile facilities, the department has failed to do so, thus far.

And the kids most likely to get sprayed are girls and other vulnerable kids, according to a December 2022 report from the Probation Oversight Commission report looking at pepper spray deployments between June 1, and September 30, 2022.

Probation staff used pepper spray more than twice as often in Central Juvenile Hall, where most of the county’s incarcerated girls are held, as in Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall, which holds a larger number of kids.

At Central, pepper spray was primarily deployed in a cluster of units that contain particularly vulnerable kids, including those identified as “developmentally disabled,” youth “who have open cases with the Department of Children and Family Services,” youth “identified as victims of commercial sexual exploitation,” and other particularly vulnerable groups of kids.

Thus, the partnership with Vera and OCYR is a step toward ending the retraumatization of kids who enter the county’s youth justice system traumatized.

The board takes action

In November 2021, the LA County Board of Supervisors voted to take steps to drastically reduce the number of girls and gender-expansive kids in juvenile halls and camps.

The motion directed the Probation Department to work with the Public Defender’s Office and others to reduce the number of girls entering the juvenile system.

Yet, between November 2021 and February 2023, when the supervisors voted to apply for the OYCR and Vera grant, the population of girls in lockup increased, according to Supervisor Hilda Solis, who authored the motions with Supervisor Janice Hahn. The numbers “didn’t go down.” The supervisor was clearly frustrated by this news.

“In case folks have forgotten,” said Solis, “we are dealing with repeated documentation that the very nature of incarcerating our youth, specifically girls and gender-expansive youths, means that they are particularly vulnerable to all forms of exploitation,” Solis said.

Thus, the second part of the February motion directed probation to “understand that this is a mandate coming from the board to find ways to safely decarcerate our girls and young women” — whether or not the county was selected for the OCYR-Vera grant, said Solis.

“Board motions are not suggestions. They do require action.”

As it turned out, Los Angeles was selected to receive assistance from Vera and OYCR.

“OYCR is working to support Los Angeles County in this critical time by working with various stakeholders to promote OYCR’s vision that young people should be in the most secure setting for the shortest time possible, consistent with public safety,” said Judge Katherine Lucero (Ret.), Director of the California Office of Youth and Community Restoration.

Through the End Girls Incarceration Action Network, OCYR and Vera “will support counties in finding ways to avoid incarcerating young people who are incarcerated for reasons unrelated to public safety, which is frequently the case for girls and gender expansive youth.”

#1: It is the court that decides to detain minors and must make findings that indicate why. Probation is required to release virtually all youth who have not committed a serious offense; #2: There is no bail in juvenile court so the court decides who gets to go home and who doesn’t – either for the protection of the youth or because they are a threat to the safety of the community because of their crime; #3: Kids are not detained for- “status” offenses; #4: In a world where gender equality is paramount (right?) decarcerating girls is obviously gender discrimination against boys; #5: Girls who are detained commit offenses that are just a violent as boys; #6 There is a separate and conveniently unmentioned aspect to this – that of a parallel BOS directive to de-populate juvenile halls. #7: As a believer that we should all be considered to be equals, some cannot be more equal than others.

This article is misleading (what WLA guest piece isn’t?) and simply regurgitates information that is already common knowledge.

No smoking gun here. Pun intended.