Youth incarceration is associated with poor physical and mental health during adulthood, according to a study published in the American Academy of Pediatrics.

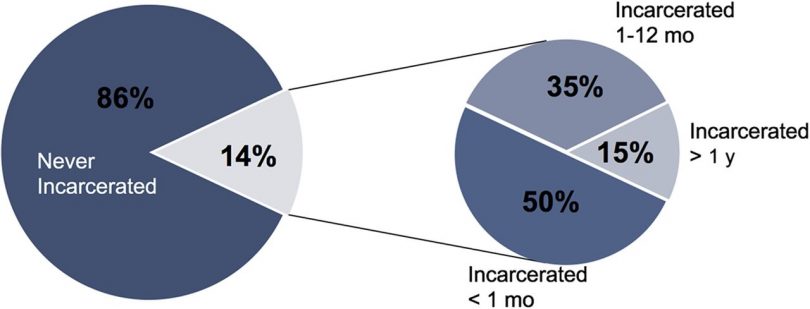

UCLA researchers gathered data from 14,344 participants from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, 14% of whom reported being locked up between the ages of 12 and 23. Of those, 50.3% were incarcerated for one month or less, 35% were locked up between one and 12 months, and 15% were incarcerated for a year or more.

Research revealed that the young people (interviewed a second time between the ages of 24 and 34) who were incarcerated for up to a month were 41% more likely to experience depression as adults than the study’s participants who had never been incarcerated. Those who were locked up between a month and a year were 48% more likely to report worse general health than their non-justice-system-involved peers. And the participants who spent more than a year behind bars during their youth were more than four times more likely to experience depression, two times more likely to have suicidal thoughts, and almost three times as likely to have functional limitations (like difficulty climbing stairs).

The study does not definitively show that these negative health effects are the result of incarceration. The researchers accounted for factors like race, income, and parents’ education level, and the young participants—especially those who were locked up for more than a year—still exhibited higher long-term health problems.

“Is it a direct effect of incarceration? Is it because they can’t get a job afterward? Is it the psychological effects and how you view yourself afterward?” lead researcher Dr. Elizabeth Barnert said to HealthDay News’ Amy Norton. “We don’t know.”

THE ACE FACTOR – TRAUMA CONNECTED WITH NEGATIVE HEALTH OUTCOMES, INCARCERATION

It’s also worth noting that justice-system-involved youth have higher rates of exposure to trauma—which negatively impacts health—than kids who have never been locked-up. Nearly all kids in the juvenile justice system have been exposed to at least one traumatic event. Research shows that kids in the juvenile justice system are 8 times more likely to suffer from post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than non-incarcerated kids in the community.

The 1997 Adverse Childhood Experiences study, by Vincent Felitti and Robert Anda, examined the long-term health effects that trauma (ACEs)—like abuse, neglect, and divorce—have on kids.

The study included a 10-question ACEs screening questionnaire, which has become the benchmark for measuring childhood trauma. (Take the quiz yourself, here.) Kids with four or more ACEs have a much higher likelihood of having emotional and physical health issues, among other serious negative outcomes.

HOW TO IMPROVE LONG-TERM HEALTH FOR YOUTH IN THE JUSTICE SYSTEM

There’s been little research so far about the long-term health effects of the justice system on young people. While the roles of health care in corrections appear to be expanding to include “evidence-based screening, assessment, prevention, and treatment,” more must be done at the community level—before and after incarceration—to improve health outcomes, Ralph DiClemente and Gina Wingood wrote in an editorial that accompanied the study.

“There is a need to mobilize partnerships between medical, juvenile justice, and community organizations to provide a continuum of adolescent-friendly crosslinked prevention and health care services that are accessible, affordable, and acceptable after incarceration, when adolescents transition from detention to the community,” said DiClemente and Wingood.

Many of the youth held in juvenile detention get their first real medical and dental attention in custody. For some, it is the first stable environment to provide structure, and proper instruction in nutrition and hygiene. And for many, it is their first introduction to mental health treatment and medications. It may well be that the withdrawal from such structure and care prompts these issues. As the article states, the researchers don’t know.