According to a recent series of research briefs on youth and young adult homelessness by Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, in the U.S., 1 in 10 young adults, or 3.5 million young people ages 18-25, experience homelessness in a year. Of that 3.5 million (73%) are homeless for one month or more.

For those young adults, homelessness means a variety of experiences, ranging from sleeping outdoors, or in abandoned buildings, or in emergency shelters, to sleeping in cars, or “couch surfing.”

Some groups of young adults are more likely to find themselves homelessness than others. That “more likely” list includes LGBTQ young people, those of color, young adults who are unmarried parents, and those who don’t have a GED or high school diploma.

Yet most dramatically, nearly half of the young adults who experience homelessness have been locked up—in their youth or in young adulthood, either in the juvenile or the adult justice system.

A new report released earlier this week by the Coalition for Juvenile Justice looks at the worrisome intersection between the justice system and homelessness, particularly for young adults.

The difficulties encountered by transition age youth.

In the last decade, neurological research has repeatedly verified that young adults are developmentally distinct from older adults, and that, in a great many ways, they have more in common with their younger counterparts, than they do adults over 25. Specifically, studies have shown that significant brain development continues well into the 20’s, particularly in the prefrontal cortex region, which regulates impulse control and reasoning.

As a consequence, according to the new Coalition for Juvenile Justice report, young people who are legally adults, but who who fall within that 18-25 year old twilight state of development now described variously as young adulthood, and Transition Aged Youth (TAY), if they don’t have a strong family support system, or worse, come from a dysfunctional or abusive family, statistically speaking, they are vulnerable to becoming homeless.

This is particularly true, according to the report, for those young adults who have been involved in the justice system.

“When youth exit the juvenile justice system, or are under probation supervision, after age 18, their parents are no longer legally required to house them, and are no longer legally entitled to make decisions on their child’s behalf,” the report notes.

Of course, write the report’s authors, “many families will welcome their children home, and healthy and supportive relationships are extremely beneficial to young people even if they live elsewhere.”

But for a significant percentage young people, returning home may not be an option. “There may be safety issues in the home, or the family’s financial situation may not allow them to take care of one more person,” or the family may simply reject the young person.

For instance, in 2016, the Administration on Children, Youth and Families interviewed 656 youth ages 14-21 who were experiencing homelessness in 11 cities across the country. When the youth were asked why they first experienced homelessness:

* 51% said they’d been asked to leave home/kicked out;

* 25% said they could not find a job;

* 24% said it was because they had been physically abused or beaten;

* 23% said it was due to a caregiver’s drug or alcohol use; and

* 13% said it was due to their own drug/alcohol issues.

Although the ACYF talked to youth in the 14-21 age group, according to the new Coalition for Juvenile Justice report, such problems are statistically worse for the 18-25 age group—especially for those who have been justice involved.

Diversion instead of over-criminalization

To help keep transition age youth involved in the justice system from becoming homeless, the 37-page report has a number of recommendations. Yet, as the first line of defense, the report recommends policies that help keep young people out of the justice system to begin with whenever possible.

For youth under 18, this means, among other things, avoiding criminalizing “survival acts” or “quality of life” offenses, write the report’s authors.

As examples the report lists “trespassing while seeking shelter on an urban rooftop, in an unused home or commercial building,” or being unable to pay fines for non-criminal citations for, say, sleeping on the street, et al, or “not receiving notice of tickets or court dates due to lack of a current mailing address, and acquiring a warrant as a result.” Or being cited for riding on the metro at night without paying, and like illegal activities that are often “survival acts” for kids feeling a problematic home life.

For transition age youth of 18-25, the issue becomes more complicated. “Having overly punitive laws and policies in place about sitting, sleeping or otherwise being in public places can lead to re-arrest and further court involvement, as well as jeopardizing probationary status,” according to the report’s authors.

To get around these problems, the report recommends pre-arrest diversion (with no documentation) to be “the norm for young adults to avoid arrests for minor infractions,” such as many of those listed above, which can trigger probation violations, and deeper system involvement for young adults who already have juvenile justice history.

As more jurisdictions, like Los Angeles County, begin exploring rigorous youth diversion programs, the report strongly suggests extending those initiatives to include transition age youth.

(The roadmap for the historic youth diversion program the LA County Board of Supervisors approved last November (and that WLA reported on here) acknowledged the need for a similar program for transition aged youth.)

Yet, in those cases where justice system involvement cannot be or has not been avoided, the report urges counties to begin “comprehensive transition planning” immediately after a kid or a young adult is adjudicated, and then to continue the planning and reentry case management throughout a young person’s justice involvement, and beyond.

At a minimum, says the report, transition planning should address:

• housing;

• family and other relationships;

• education;

• employment;

• life skills and healthy relationships;

• physical and mental health;

• juvenile records, adult records, and other legal issues; and

• access to vital documents

Los Angeles County and homeless transition-aged youth

The report goes on to list other important ways to address the increasingly pressing national problem of keeping justice involved young adults from becoming homeless, and to help those who are already homeless.

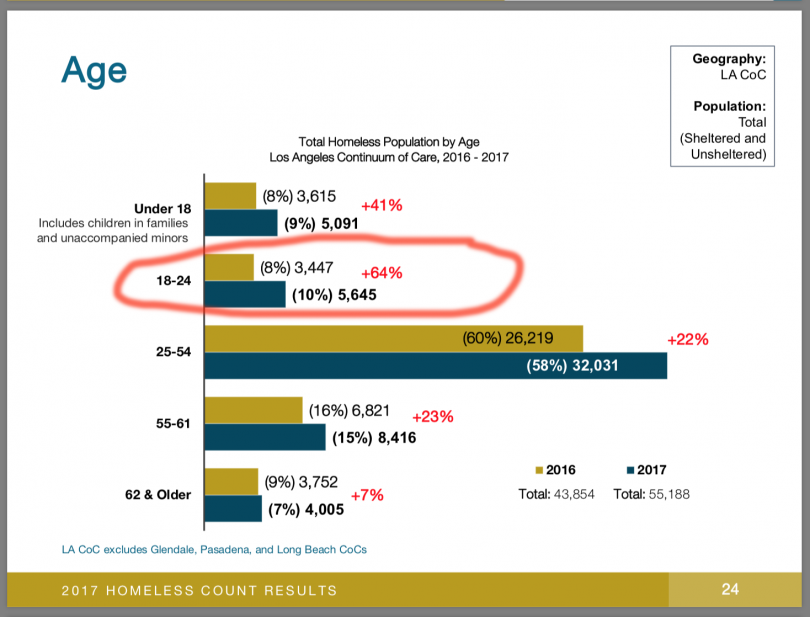

In Los Angeles County, where homelessness has reached crisis proportions, the latest homeless count showed nearly 6000 18-to 24-year-olds on the streets (5,645, to be exact). This 2017 count was a staggering 64 percent increase over the 2016 count for homeless transition age youth. (Some advocates believe that much of the startling rise for this age group is due to the fact that authorities got better at finding out where the homeless young adults were to be found, thus in 2017 the count was more accurate.)

So, with these stats in mind, how is LA County doing with helping its justice-involved transition aged youth stay away from homelessness and further system involvement?

According to the extremely comprehensive LA Probation Governance Study released on April 10, 2018, and researched and written for the county by Resource Development Associates (RDA), LA County could do a lot better.

The transition to adulthood “is especially challenging for justice-system-involved young adults,” the RDA authors wrote, “as they are more likely to have personal histories that can further disrupt psychosocial development.” And in general, “crime-involved young adults have a higher likelihood of parental incarceration, poverty, foster care, substance abuse, mental health needs and learning disabilities,” all of which can lead to a “disproportionately high percentage of arrests and prison admissions.” And all of which can also lead directly to homelessness.

According to the RDA report, in LA County “the unique needs of young adults are not being met” in either the county’s juvenile or adult justice systems.

Studies suggest, wrote the RDA authors, that incarceration creates additional barriers to educational attainment, stable employment, housing, health care, and relationships. “The multiple disadvantages that these young adults face suggest that correctional programming, both in secure facilities and in the community,” must do much better in addressing the multiplicity of issues that stand in the way of system-involved young adults succeeding.

California victory stories

There are some things, however, that LA County and other California counties are doing right when it comes to addressing the challenges that can lead system-involved transition-aged youth into homelessness.

For example, the Coalition for Juvenile Justice report points to San Francisco’s Young Adult Court (YAC), which serves eligible 18-to-24-year-olds, and “strives to align opportunities for accountability and transformation with the unique needs and developmental stage of this age group.”

The court, launched in 2015 by San Francisco District Attorney George Gascon, together with then SF probation chief, Wendy Still, is specifically designed to “align opportunities for accountability and transformation with the unique needs and developmental stage of this age group,” according to the court’s website.

In a recent assessment of the YAC, a significant percentage (32%) of young people participating in the court program had experienced homelessness in the past, and 13% were currently experiencing homelessness when they entered the program.

Participation in the YAC includes case management services, a wellness care plan (jointly developed by the participant and a case manager) “which can include housing support, and a “rewards and consequences” system to help encourage positive behavior and better outcomes for the young adults the court serves.

And, in Los Angeles, in November 2017, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted in favor of a plan to improve outcomes for so-called “disconnected youth” between the ages of 16 to 24 who are not in school and are not working. The designation includes young people who are in the foster care system, those who have dropped out of high school, formerly incarcerated youth, homeless individuals, and young, low-income parents. (Just under one in six LA young people age 18-24 falls into this “disconnected category. In certain regions of the county, such as South Los Angeles, the number shoots up to nearly 23 percent)

The plan, triggered by a motion authored by supervisors Mark Ridley-Thomas and Sheila Kuehl, calls for the new initiative designed to “improve educational and employment outcomes [for this group of young people] from cradle to career” to be implemented by January 2019.

Then in May of this year, LA’s supervisors approved a motion by Supervisors Sheila Kuehl and Hilda Solis, to develop a three-year pilot program overseen by LA County Probation, which involves transforming one of the county’s juvenile detention camps, Camp David Gonzales, into a professional training facility for young people age 18-25 who have come in contact with foster care, the justice system, and/or who have experienced homelessness.

The proposed program will include free housing, and technical training in the fields of building and construction trades, or food service/culinary arts—along with various wrap-around services, life skills training, and guaranteed job placement.

“It will be the very first program of its kind in the nation,” said Supervisor Kuehl.

So, yes, some progress is being made. But, in California, as in most other states in the union, there is still much left to be done when it comes to helping transition age youth avoid homelessness—especially if they’ve had brushes with the justice system.

The obvious answer to this problem is to finish school and not commit crimes, at least not until the crimes are made legal by the California Legislature or the State’s voters

That’s interesting that you think the answer is one-dimensional and so simple to correct. If your prescribed solution was actually an antidote, I’m certain that you would go far by showing how well it works. However, like most problems, it is more likely that youth homelessness has complexity and many broken cogs feeding into a systematic problem. For example: the school to prison pipeline, the affordable housing crisis and gentrification as a by-product of red-lining, and oppressive lending policies, deprioritizing funding for schools, community centers, and healthcare facilities, food deserts, fractured families from an array of touchpoints including mass incarceration and unequal prosecution during the so-called “drug wars.” By critically engaging in the layers with empathy and working together as a community, we can address these issues that affect all of us.

I have no empathy for people who commit crimes. Lots of us grew up under circumstances less than ideal and didn’t why excuse those who turn to breaking the law? Sorry, doesn’t wash.