EDITOR’S NOTE: Earlier this month, we co-produced a story with The Chronicle of Social Change about the difficulties that arise when California foster children wind up in what is known as: out-of-county placement.

The story, by Daniel Heimpel, looked at the problems faced by one bright and active teenager who was taken into foster care and subsequently placed with a family that lived a county or two away.

The story below, by Melinda Clemmons (also co-produced with CRC) looks at the problems faced by a husband and wife who took in another family member’s the out-of-county child (or, in this case, children), and thus found themselves dealing with the bureaucratic systems of not one, but two different counties.

The Two-County Headache of Becoming Out-of County Foster Kin

by Melinda Clemmons

Mariana Rivera* had her hands full.

Holding her newborn niece, she filled out the paperwork for the infant’s first medical appointment while her four other nieces and nephews, all under the age of 10, ran around the clinic’s waiting room.

“We had just gotten two of the kids earlier that day, and the other two a couple days before that,” Rivera said. “They weren’t used to us yet, and they were confused about why they were with us, so they couldn’t sit still.”

It was the spring of 2014 and, after nine months waiting for their home to be approved, Rivera and her husband had just become relative caregivers to her brother’s five children. The children, and now the baby, had been removed from her brother and his girlfriend, their mother, and placed in foster care by child protective services in Solano County, the eastern-most county in the North Bay area of California.

Knowing that the siblings would likely be separated if they went into non-relative foster care, the Riveras agreed to take them all into their home in neighboring Yolo County when asked by her brother, even though that meant their own 18-year-old son had to move out to make room in their small house.

“We wanted the kids to stay together,” Rivera said. “So we started the process of getting approved right away.”

Over one-third of the children in California who have been removed from their homes due to abuse and neglect are placed with relatives. The Riveras’ nieces and nephews are among the 20 percent of foster children in the state who are placed in a different county from the one in which they were removed, a circumstance that, as the Riveras would find out, brings complications in terms of support services, funding streams and the sheer logistics involved in taking care of children in foster care.

According to Aaron Crutison, deputy director of Solano County Child Welfare Services, relative caregivers are crucial to the department’s focus on permanency for children and strengthening families.

“When we remove a child,” said Crutison, “we’re placing that child in the least restrictive environment while we work with the family and their issues. A relative placement is someone they’re familiar with…so we minimize the trauma to the child when a relative steps in while we work with the family.”

Juggling paperwork, a newborn and four restless children at the clinic, Rivera was quickly finding out that all it takes is a little bureaucratic foul-up to make the already challenging job of caring for traumatized children even harder.

She had driven from her own home in Yolo County to the clinic in Solano County for the baby’s appointment, which had been scheduled by the Solano County hospital where she was born just three days earlier. But after she completed the registration forms at the Solano clinic, she was told that the baby could not be seen in that clinic since she and her siblings now resided in Yolo County with the Riveras.

A frustrated Rivera was advised to go to a clinic in her county of residence, which she did the next day. There she was told that the Yolo clinic could not see the baby either, since as a newborn, she was still on her mother’s MediCal health insurance in Solano County. According to the intake staff at the clinic, Rivera would need to visit a clinic back in Solano County.

When handing over the baby two days after her birth at the hospital in Solano County, the infant’s social worker gave the Riveras her essential paperwork, including the relative foster care placement papers, which they signed. The mother’s MediCal information was absent from the file, a fact the Riveras didn’t learn until they needed it for the Yolo clinic visit.

“The worker should have known that since we lived in a different county, there might be trouble with [the MediCal card] but I don’t know if she knew,” Rivera said.

When she called the worker to untangle the mess, the worker said she did not know how to resolve the problem, and would have to check with her supervisor and get back to her.

“We kept going back and forth to the clinics,” Rivera said. “I called and called the worker until she fixed it.”

The baby was finally seen by a doctor at the clinic in Yolo County, a week after her original appointment.

OUT-OF-COUNTY KIN CARE

As the Riveras discovered when they were ping-ponged between clinics, living in a different county than the one in which your foster children originally resided means an array of complications that go well beyond the expected difficulties of dealing with the state’s overwhelmed foster care system.

While Aaron Crutison of Solano County Child Welfare could not speak about a particular case, when told of the Riveras’ frustration in trying to navigate the two county health care systems, he acknowledged the system has challenges.

“We do all we can to make sure that does not happen,” Crutison said.

Waiting nine months for their home to be approved to receive the children was difficult for the Riveras, as they felt the children needed to be with family after what they had been through. While they did not know the details, they understood that the cause of removal was neglect.

“My brother had told me some things, but I didn’t know the whole story,” Rivera said. “But I knew it wasn’t a good environment.”

In addition to the bureaucratic mix-up at the clinics, the Riveras have faced multiple challenges imposed by the distance between their home in Yolo County and the children’s home county of Solano, both during the nine-month-long relative caregiver approval process, and now while they have the children in their care.

For instance, while the Riveras waited for the wheels to turn so the children could be placed with them, the siblings were split up into two different foster homes in Solano County. Anxious to provide their nieces and nephews with some sort of emotional continuity, they traveled over an hour each way to visit the children as often as they were allowed to visit and could manage with their own schedules.

Now that the four children, and the baby, are finally living with them, Rivera drives the same distance once a week to deliver her nieces and nephews for visits with their parents.

In addition, after the children were placed in their home, the kids’ social worker told the Riveras about something called the Foster and Kinship Care Education program in Solano County. Sensing she needed some kind of support, Rivera went to one of the meetings. “It took me an hour to get there, and the meeting was a couple hours, then I had to drive home. It took up the whole day.”

When the children were assigned to a new social worker this past May, she told the Riveras about the Foster and Kinship Care Education program at Woodland Community College near their home in Yolo County. Rivera attends as often as she can, and says that she wishes she had known about it earlier as she gets a lot of support from the staff and fellow relative caregivers who attend the program.

UNEQUAL FOSTER CARE FUNDING FOR RELATIVES

In the spring of 2014, when the children and the baby were placed with the Riveras, relative caregivers did not receive the same level of funding that non-relative foster parents received. The state provided no foster care support to relatives of children who were not eligible for federal foster care support, which accounts for one-third of California’s foster children.

Relatives caring for children who were not eligible for federal foster care support were told to apply on their own for CalWorks and food stamps.

The Riveras did so, and found the process “very frustrating and confusing.” Moreover, as they live “more or less paycheck to paycheck,” the couple hundred dollars per month they received for each child left them struggling to pay for the children’s needs.

Things improved in June 2014 when, thanks in large part to a statewide advocacy effort led by the Step Up for Kin coalition, Governor Jerry Brown signed into law the Approved Relative Caregiver Funding Option Program. Also known as ARC, the program provides relative caregivers financial support equal to the basic foster care benefits. (It does not pay for specialized care, something that the coalition is working to change.)

“I am very happy that Solano County opted in to this program,” Rivera said. The Riveras finally began receiving the basic foster care rate for each child earlier this summer after the children had been in their home for more than a year.

Inequities still exist, however, as not all counties have opted into the program. Relative caregivers whose foster children originate from one of the 15 counties that have not opted in do not get the ARC dollars even if they themselves live in a county that has accepted the ARC option.

REUNIFICATION AND PERMANENCY

Rivera’s brother and his girlfriend are attending counseling, working to reunify with their children, and have recently asked Rivera to be their “support person” if the children are returned to them.

She was very glad to agree to do that since she wants to remain involved in the children’s lives. As a relative who stepped in during a time of crisis, she does not feel prepared for the children to leave her home.

“When you’re a foster parent, you’re more mentally prepared for it when the children come to you and when they go back home,” Rivera said. “But when you’re family, you can’t believe it when it happens. It’s a shock. It’s like they’re your own children.”

“I love them” she said, “and I’m going to miss them.”

For now, Rivera enjoys watching the younger children run to the older ones when they come home from preschool.

“They need each other,” she said. “We wanted to keep them together, in spite of the struggles, and we have.”

Melinda Clemmons is a reporter and the Marketing Manager for The Chronicle of Social Change.

* The names of the relative caregivers and a few details in this story have been changed to protect the identity of the children in their care.

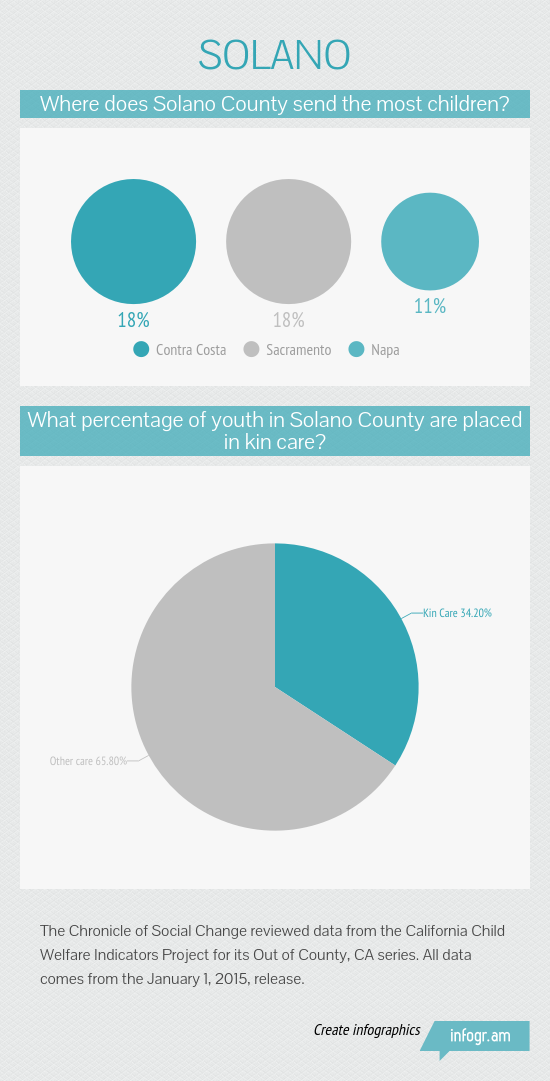

Meiling Bedard and Maria Akhter contributed to the data visualization for this story.