Before I tell you about Anna Politkovskaya and her shrapnel, let’s take a quick look at the relationship between journalists and the war in Ukraine.

Since February 24, 2022, when Putin publicly authorized Russian forces to begin missile and artillery attacks on the independent democratic nation of Ukraine, it has been possible to watch in real time the shattering effects of those deadly attacks on the Ukrainian people.

The Vietnam War was known as the first war to be televised. The war on Ukraine is one we are able to carry in our pockets 24/7 via our cell phones.

Many of most devastating words and images are provided by ordinary Ukrainians who are determined to document the terrible events they and their families are hoping to survive.

The rest of what we’ve been watching close-up/from afar is produced by the reporters who risk everything, day after day, to bring us the latest in heart-tearing news.

Sometimes the cost of that news gathering has been terribly high.

On March 1, 2022, Russian military forces shelled a television tower in Kyiv, Ukraine, killing five people including camera operator Yevhenii Sakun, 49, who had been covering the invasion. At that moment, however, was working as a camera operator for the Ukrainian television station LIVE when he was killed. He was identified by his press card.

Last week, we learned that 55-year-old Pierre Zakrzewski, a cameraman for Fox News, was killed while reporting alongside Fox News reporter Benjamin Hall, who was badly injured, when incoming fire hit their vehicle outside of Kyiv in Horenka.

A few hours later we further learned that Oleksandra Kuvshynova, a 24-year-old Ukrainian reporter who was acting as a consultant and guide for the Fox News team, was killed alongside Zakrzewski.

Two days before the Fox reporters died, Brent Renaud — a 50-year-old, award-winning filmmaker, journalist, and documentarian from Little Rock, Arkansas — was shot dead by Russian forces while reporting just outside of Kyiv.

Around that same time, Russian soldiers began hunting the two person team of AP reporters who had spent 20 days bringing us the agony of the residents of Mariupol, including harrowing coverage of the shelling of the city’s maternity hospital, which also contained children.

The two AP journalists wanted to stay to continue to report on the wounded city, explained Mstyslav Chernov, video journalist for the Associated Press, in his account of the destruction of the city Mariupol. But Ukrainian soldiers whisked him and AP photographer Evgeniy Maloletka into vehicles, hoping to get them out of the area.

“If they catch you, they will get you on camera and they will make you say that everything you filmed is a lie,” a police officer told the two AP reporters. “All your efforts and everything you have done in Mariupol will be in vain.”

(As of March 15, officials estimated that approximately 2400 civilians had been documented killed in Mariupol alone.)

Now, there is concern among the international press corps that Ukrainian photojournalist Maks Levin has not been heard from since March 13, when he was reporting in the Vishgorod district, north of Kyiv, where he had been capturing both the fighting and fleeing civilians.

Levin dropped from contact around the time that Ukrainian reporter Victoria Roshchyna, who had been missing for days, was freed by Russian authorities and made it back to Ukrainian-controlled territory.

Anna’s shrapnel

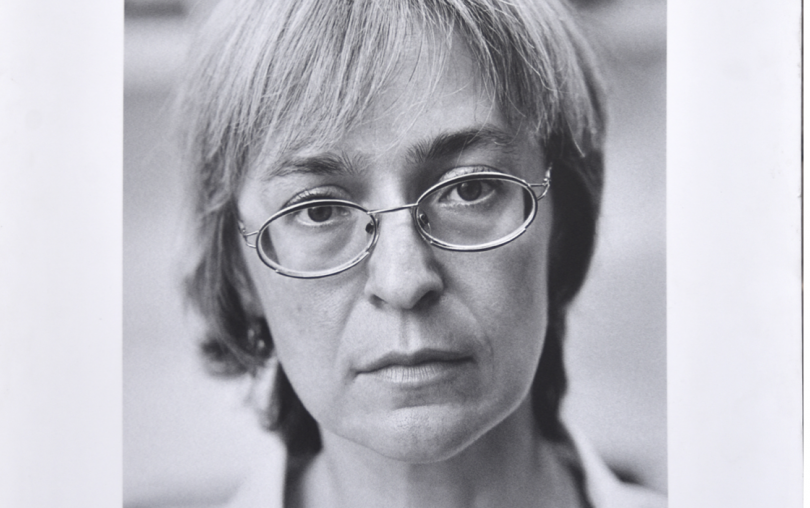

Since this war began, I’ve thinking repeatedly of another remarkable reporter, Anna Politkovskaya, the fearless Russian journalist and nonfiction writer who was honored throughout the world for her powerful stories, which documented, among other horrors, the terrible effect of Vladimir Putin’s war in Chechnya on ordinary Chechens trying to live through it .

I met Anna in 2002, when she came to Los Angeles so that a journalism organization of which I was then a board member, could present her with our Freedom to Write Award.

Four years later, when she was about to publish what arguably would have become one of her most consequential stories in Novaya Gazeta, the publication for which she wrote, someone shot her four times as she was about to enter the elevator at the entrance of the Moscow apartment block where she lived.

A month or so after Politkovskaya’s death, I learned from two friends of mine, who knew her far better than I ever did, that whenever she was asked to speak to some organization that wished to honor her, before she left her apartment, she’d tuck a piece of shrapnel in her purse to use when giving her speech to the crowd.

She admitted it was bothersome to justify the shrapnel’s presence to airport security officers. But she felt the hassle was worthwhile because she’d found, when it came to giving her audiences a window into the everyday reality of living in a war zone, nothing beat the sight of that shrapnel.

The small, twisted piece of metal was the revelatory detail that bypassed the intellects of her listeners and engaged them at a deeper level with the story she was telling.

These past weeks, as my thoughts returned to this brave and brilliant woman, I was reminded of her conviction that so much of any good reporter’s job is to persuade others to care about painful but important stories and issues.

And so the shrapnel.

In the years I taught journalism at USC’s Annenberg School, and literary journalism at UC Irvine, when I talked to my students about the art of finding the “telling detail” that was critical to good reporting, I would talk about Anna and her shrapnel, and how she’d employed the technique in order to breathe life and urgency into the difficult issues she investigated in her columns, features, and books.

Of course, it was her potent reporting that got Politkovskaya killed, contract style, by someone who shoved her body inside the elevator of her apartment building, along with the Makarov pistol they used to shoot her.

She died on October 7, 2006, which was also the date of Vladimir Putin’s 54th birthday.

In October 2021, almost exactly fifteen years after Anna’s death, Dmitry Muratov, the editor-in-chief of Novaya Gazeta, the Russian publication where she had worked, became the co-winner of the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize, sharing the prize with Maria Ressa, an investigative journalist from the Philippines

The day before Murative was to accept the prize, he stood outside the Moscow apartment block where his publication’s most famous journalist was murdered, and told the gathered crowd that he got prize because it cannot be awarded to the dead.

He said the prize also honored five of Anna’s colleagues who had been killed since 2000 because of their own reporting.

Anna, who had survived two earlier attempts on her life, one of them a probable poisoning, characterized herself as “someone who describes what happens to those who cannot see the events” themselves.

Just thought you’d like to know.

Photo of Anna Politkovskaya courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

________

As we all know in 1991–thirty-one years ago–the fifteen republics of the Union of Socialist Republics dissolved into fifteen different countries, including the two former Soviet Republics of Ukraine & Russia, who are next door to one another.

At that time Russia wasn’t any bigger than any other Soviet Republic. Since then it has absorbed other former Soviet territories so that now, today, it is the biggest country in the world, four times bigger than the contiguous United States; we can see Russia from Alaska.

Vladimir Putin blames the U.S. for the dissolution of the U.S.S.R., and he’s probably right.

Yippeee, we won the Cold War.

Compare our–the U.S.–reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine with our reaction to, say, Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait or Argentina’s invasion of the Falkland Islands.

Compare.

Putin says he’ll nuke us if we meddle in Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine.

That brings me to my service as an Army paratrooper in 1957-60–yeah, I’m that old.

Then, Army paratroopers could touch down by parachute anyplace in the world seventy-two hours after issuance of the “Go” word. With the advent of jet transports like the C-17 it can be done in 18 hours.

Now pay attention to this: we were briefed–remember: this is 1957-60–that the Soviets could send a salvo of nuclear tipped ICBMs over the North Pole that could blanket the entire U.S. from coast-to-coast in just

one hour.

What maintained the peace was MAD: Mutual Assured Destruction.

We can do to them what they do to us.

Putin has said that he’ll nuke us if we meddle in his invasion.

Does he think that he can safely breach MAD?

Putin thought the Ukrainian operation would be a two-day operation; it’s been a month now.

No Blitzkrieg there.

Fingers crossed his nuclear-tipped ICBMs are just as bad.

Journalists, the heros, like you mention report observances. Who, what, where, when, and sometimes why. Decades ago I attended my first class and was taught there is no story without a controversy. Some have gone on to spread rhetoric inflaming partisan talking points sometimes verifiably wrong, to promote controversy. Fake news from fake journalists.