A growing body of dozens of studies and reports has revealed the far-reaching negative effects of childhood exposure to crime and violence on the wellbeing of individuals, families, and society.

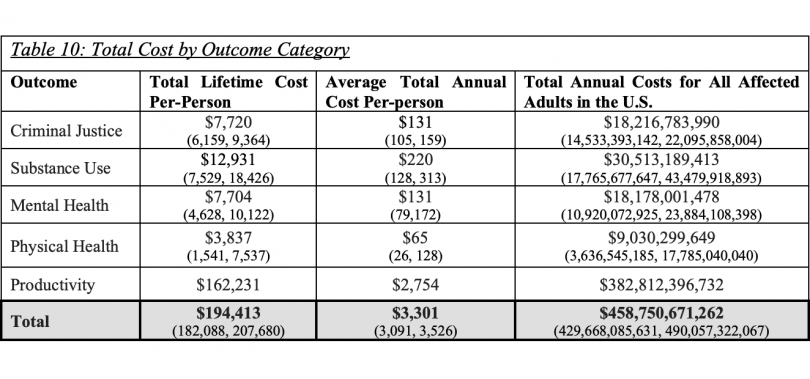

Now, researchers have endeavored to put a price tag on all that trauma. Childhood exposure to violence costs the United States an estimated $458 billion per year, according to a report by Michal Gilad, a researcher at the University of Pennsylvania Law School, and the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Abraham Gutman. And that estimation, they say, is likely a conservative one.

Moreover, “the estimated annual costs of mass incarceration range between $80-182 billion, which is less than half of the estimated annual costs of the ongoing neglect” of what Gilad calls the Comprehensive Childhood Crime Impact or “Triple C Impact.”

Nearly two out of every three children in America have been “affected by at least one form of crime exposure during their childhood,” states the report.

People who have experienced multiple childhood traumas — including abuse and witnessing violence, neglect, substance abuse in the home, parental divorce, and parental incarceration — have a much higher likelihood of having mental, social, and physical health issues, including depression, PTSD, abnormal neurological development, missing work, criminal justice system-involvement, lower educational achievement, drug use, alcoholism, suicidality, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, cancer, and early death.

“Children whose lives are touched by crime are left with deep scars that gravely affect their mental and physical health, as well as their life outcomes,” Gilad and Gutman write. These negative impacts on the individual ripple out, and carry heavy costs for society.

Outpatient treatment for opioid use disorder, for example, costs approximately $5,980 per patient, per year. An individual’s lifetime cost of drug use costs an estimated $245,960. The researchers estimated that the national financial impact of smoking, alcoholism, and drug use disorder rang in at approximately $33 billion. And healthcare expenses for people who experienced child abuse are estimated to be $7,500 more per person, per year, than for people who did not experience abuse as a child.

Negative economic impacts abound, as well.

Individuals directly victimized as children also experience an average income deficit of between $5,000 and $6,000 per year, at peak earning, research shows. Kids with incarcerated parents are estimated to make less money as adults than their peers, as well.

Public assistance use rates increase by as much as 65 percent to 100 percent among Triple-C Impacted people, over people who were not exposed to crime as children.

Yet local governments, states, and the federal government do far too little to address the issue of childhood trauma.

” … Little is done on the policy level to heal the open wounds,” The report says. “The majority of children harmed by crime do not receive the much needed services to facilitate recovery from trauma.” And access to the services that do exist in states is often “obstructed by a myriad of bureaucratic hurdles and flaws in the system’s design.”

“Money talks,” say Gilad and Gutman. The duo hopes that by putting a sticker price on childhood exposure to crime, public officials will be compelled to invest in ultimately money-saving prevention and intervention strategies that will “alleviate the injurious and costly outcomes for children affected by crime exposure.”

One way the state of California has vowed to address the issue, is with a $3.85 million payment to the California Firearm Violence Research Center at UC Davis, where researchers will use the money to develop gun violence prevention training programs for medical and mental health care providers.

Governor Gavin Newsom signed AB 521, which authorized the funding and the research, last Friday.

Kaiser Permanente announced a similar investment last week. The medical group has set aside $2.75 million for addressing childhood trauma and its effects. The money will fund research focused on identifying clinical and community-based interventions.

And California’s first-ever Surgeon General, Dr. Nadine Burke Harris soon hopes to ensure that doctors screen every child for trauma.

Burke-Harris, a pediatrician who founded and led the Center for Youth Wellness, has long been rel="noopener" target="_blank">a leading voice in the conversation about the intersection of childhood trauma and public health.

Universal screening for trauma will not only improve children’s well-being, Gilad told WitnessLA, but it is “also very budget-conscious and has the potential of facilitating substantial long-term fiscal savings for the state.”