On January 1, a new state law, SB 1421, returned to the public long-withheld access to law enforcement personnel records.

Supported by the fresh police transparency law, media groups and civil rights organizations wasted little time submitting public records act requests in the new year, hoping to gain access to information on police misconduct, use-of-force incidents, and other newly available records.

Hoping to shield their officers, law enforcement unions in Los Angeles and across the state have taken the issue to the courts, however, filing petition after petition to (at least temporarily) block the release of records dated before January 1, 2019. Their efforts have been rewarded.

Attempts by the ACLU, the LA Times, the Sacramento Bee, Reason, and many others to obtain records ranging from the fatal police shootings of Oscar Grant and Stephon Clark, to LA County Sheriff Alex Villanueva’s reinstatement of Caren Carl Mandoyan–and even Villanueva’s own discipline history–have been blocked.

Changes Under SB 1421

The new law at the center of all these legal battles, SB 1421, returns to the public the right to know when police officers misbehave on the job, and when they use force in the line of duty.

Four decades ago, in 1978, California barred public access to this information, making it the most secretive state in the country when it came to law enforcement records. Prosecutors in CA have not even had the authority to access the records of officers found to have committed misconduct under the color of authority, including those with a history of planting evidence or lying in police reports.

As of Jan. 1, SB 1421 requires law enforcement agencies statewide to release records of incidents in which officers use force–specifically, when cops discharge their firearms or Tasers, use a weapon to strike a person’s head or neck, or use force that results in serious bodily harm or death.

The legislation also makes records of on-duty sexual assault, including when cops exchange sex for leniency, available to the public.

SB 1421 also opens up access personnel records of officers who are found to have been dishonest in the “reporting, investigation, or prosecution of a crime.”

But the roll-out of the new law has been piecemeal, as law enforcement unions fight to keep personnel data out of the hands of the media and the public.

The Battle

On January 2, the California Supreme Court denied a San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department union’s last-ditch efforts to drastically shrink the scope of SB 1421 to only apply to records created after Jan. 1, 2019.

But the legal battle is far from over.

In a series of petitions filed across the state, unions and law enforcement officials have argued that SB 1421 does not include any definitive language regarding retroactivity, and applying the bill to pre-2019 documents would be severely harmful to officers, and a massive strain on department resources. Sen. Nancy Skinner, the bill’s author has said that the bill was intended to be retroactive–applying to all eligible records possessed by police agencies, which is why law enforcement groups lobbied so hard to stop its passage. (State law requires law enforcement agencies to retain misconduct and use-of-force records for five years, but many agencies keep records beyond the five-year mark.)

Agencies including the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, the Los Angeles Police Department, the Orange County Sheriff’s Department, the Riverside Sheriff’s Department, and the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department have all legally avoided, at least temporarily, releasing records of conduct and incidents occurring earlier than 2019.

Last week, on Jan. 24, the LA County Superior Court temporarily blocked the department from applying SB 1421 retroactively.

More than three weeks before, on Jan. 2, Reason decided to “take SB 1421 for a spin,” and requested any discipline records available for LA County’s new sheriff, Alex Villanueva. During his campaign, Villanueva reported that he had been unfairly disciplined in the past, in retaliation for challenging alleged discrimination against Latino deputies within the department.

“We didn’t necessarily think Villanueva had done anything wrong,” wrote Scott Shackford, an associate editor at Reason. “He may well have been targeted for political reasons, as he claimed. But because we don’t have access to those records, all we’re left with is Villanueva’s account of his work history.”

Under the state’s public records laws, the LASD had 10 days to respond to Reason. On the ninth day, Jan. 11, the department sent the publication a 14-day extension request, explaining that records had to be collected from “field facilities or other establishments.”

It appears the delay was a ploy.

Five days later, on Jan. 16, the Association for Los Angeles Deputy Sheriffs (ALADS) filed a petition to temporarily block SB 1421’s retroactivity.

On Jan. 22, having waited, like Reason, for several weeks, the LA Times and Southern California Public Radio (KPCC) filed a lawsuit accusing the LASD of failing to turn over records in a timely fashion. The LA Times sought information related to Villanueva’s controversial reinstatement of Caren Carl Mandoyan, a deputy accused of domestic abuse and stalking. KPPC wanted records related to Deputy Gonzalo Inzunza, the subject of the podcast, “Repeat,” who fired at four people within seven months.

On January 24, just before Reason’s extension expired, and two days after the LA Times/KPPC lawsuit, the courts approved ALADS’ temporary stay, which, like the other orders, effectively blocked the release of pre-2019 records.

A hearing on this particular case is scheduled for Feb. 15.

Those seeking use-of-force or misconduct files for Los Angeles police officers were also left in the dark.

In December, the City of Los Angeles urged the court to deny the Los Angeles Police Protective League’s request for its own temporary restraining order. “The most reasonable interpretation of SB 1421…would require the Department to disclose Specified Records created before 2019 that it maintains in its possession, pursuant to a valid [California Public Records Act] request,” the city argued. “The Legislature appears to have intended SB 1421 to allow for disclosure of all Specified Records in an agency’s possession, regardless of when they were created.”

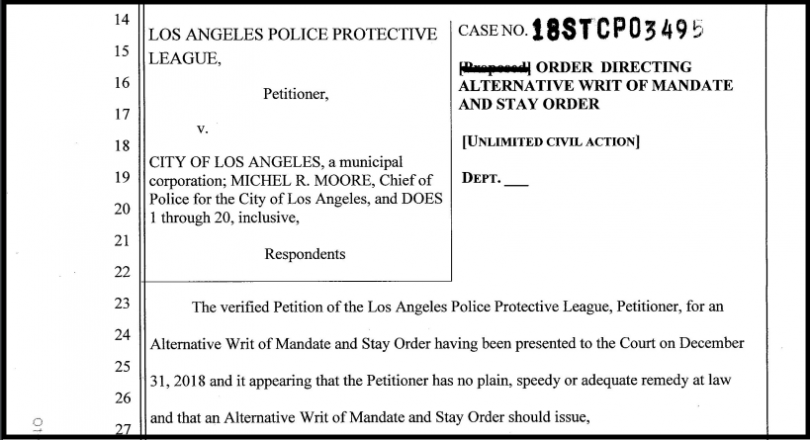

The LAPPL prevailed. On December 31, the LA County Superior Court granted the police union a temporary stay, blocking the LAPD from releasing records retroactively, pending a Feb. 5 hearing.

Orange County, like its neighbors, has been spared from turning over past files.

On January 17, an Orange County judge sided with the Association of OC Deputy Sheriffs, and issued an order limiting the scope of what documents the OC Sheriff’s Dpeartment must release under SB 1421.

The Voice of OC, KPPC, and the LA Times appeared in court to fight for the right to access past police records.

Additionally, deputies’ unions in Ventura and Riverside Counties have successfully staved off SB 1421.

The Fight in NorCal

In Northern California, news organizations are also battling on behalf of increased transparency, with mixed results.

Last Friday, the Sacramento Bee and the LA Times filed a lawsuit against the Sacramento Sheriff’s Department over the agency’s refusal to apply the new law retroactively.

In response to the newspapers’ Public Records Act requests, the department said it would not release the records in question without “clear legal authority to release such records” had been established.

Like Sacramento, the San Jose Police Department has also reportedly chosen to hold off on answering requests for records as it “monitors” litigation that may protect the department from disclosure.

Contra Costa County and police departments within the county–in Antioch, Concord, Martinez, Richmond, and Walnut Creek—are safe from releasing pre-2019 docs.

A hearing for all of the Contra Costa agencies will be on Feb. 8.

In Berkeley, city officials sided with the local law enforcement union, refusing to turn over docs. Out of “good faith,” Berkeley reported to the publication, Berkeleyside, that there were no sustained allegations of sexual assault or dishonesty within the last five years.

Not All Police Agencies

One tiny Solano County City, bucking the trend, has released personnel records

under SB 1421. KQED, the San Jose Mercury News, and Capital Public Radio obtained recordsrevealing that two since-fired officers made problematic arrests with trumped up charges. One of the officers used a deadly chokehold, and failed to call for medical assistance.

The San Luis Obispo County Sheriff’s Dept. and Santa Barbara Police Department have also reportedly released SB 1421 records.

In San Mateo County, KQED and the San Jose Mercury News reporters successfully collected information from the city of Burlingame, where a former officer was found to have exchanged leniency for sex. The Burlingame Police Department, however, reportedly charged KTVU more than $3,000 to redact and prepare the records related to the single officer. In contrast, the nearby city of Fremont charged KTVU $171.40 plus shipping to redact 1,174 pages detailing four officer-involved shootings.

The Shredders

Besides the legal fight, police agencies and cities are arming themselves against SB 1421 with shredders, eliminating personnel records created before January 1.

The Inglewood City Council voted to destroy more than 100 Inglewood PD shooting records and other internal investigation documents from 1991 to 2016.

The Long Beach Police Department, too, destroyed records. Both Inglewood and Long Beach said that their shredding was just part of regular housekeeping.

Next door, in Orange County, Santa Ana Police Chief David Valentin has sought permission from city councilmembers to destroy eight boxes of police records that would be subject to SB 1421 disclosure.

In response to SB 1421, the Santa Clara County city of Morgan Hill voted to retain officer-involved-shooting records for just two years, in cases where an officer was cleared of any wrongdoing. Other records subject to the five-year retention requirement will be destroyed after those five years.

It’s likely that these are not the only cities and agencies moving to destroy personnel and administrative investigation records.

WitnessLA will have more in the coming days and weeks about the legal tug-of-war over police transparency in California, as this issue will not be going away soon.

> Santa Barbara Police Department have also reportedly released SB 1421 records.

Could you give more detail about this? Who got the records and what did they get? Can they be found online?