LIKE A THIRD WORLD COUNTRY PRISON”

On Valentine’s Day of this year, which was a Sunday, Los Angeles County Probation commissioner Azael “Sal” Martinez showed up unannounced at the county’s Central Juvenile Hall to do an inspection, and what he discovered alarmed him.

Much of the reason Martinez came to LA county’s largest juvenile hall that day was to bring bags full of valentine cards and candy for the kids who were locked up in the place. But he also came to juvenile hall to review conditions at the facility itself.

“My role is to make sure that the kids are okay, and that the plant is livable,” he has said in the past about these site reviews.

According to the official report he wrote after his visit, Martinez found instead “deplorable conditions” throughout much of the facility.

Sal Martinez is a former teenage gang member and drug dealer who rerouted his life to become a highly respected community activist who is on his second term as a member of the LA County’s Probation Commission, appointed for a seat on the 15-member body by LA County Supervisor Hilda Solis.

(Former supervisor Gloria Molina selected Martinez for his first term on the commission.)

Martinez does not take his responsibilities lightly. In addition to attending the commission’s twice-monthly meetings, he is also what he describes as “a field commissioner.” In practical terms, this means he makes unannounced visits to the department’s various juvenile facilities, like central juvenile hall.

After each visit, he writes a report about what he sees, which is distributed to his boss, Supervisor Solis, to higher ups inside the probation department, including to the chief. And then, eventually, it goes to the commission, where it enters the public record.

Probation department officials who work at the sites Martinez visits are reportedly not always entirely thrilled by the commissioner’s habit of parachuting in without advance warning. But Martinez wants to see the house as it really is, so to speak, not after it has been tidied up to impress the guests.

Last year, for example, Martinez made unscheduled visits to four of the county’s regional offices where juvenile probation officers are supposed to meet with their young clients as part of the department’s new Camp Community Transition Program (CCTP). The program, which was put into place two years ago, is meant to provide services for young people transitioning from a juvenile camp, hall or other placement to their home community. However, what Martinez found at the four CCTP offices he visited, raised “serious issues and concerns,” he wrote. “The visit was alarming and extremely unacceptable.”

(WitnessLA has the full story on Martinez’ site visits to the CCTP offices here.)

Then, in February of this year, Martinez made the Valentine’s Day visit to Central Juvenile Hall, and the subsequent report describing “deplorable” conditions that he compared to a “Third World country prison.

THE AWFUL STENCH

This was not Martinez’ first site visit to Central Juvenile Hall, as he noted in his latest report. He comes here with some regularity. Thus he expected to find some of the improvements promised at the last visit.

Instead he found a startling list of problems, and what his report alleges to be the failure of leadership to take appropriate steps to solve the problems.

In one unit, for example, there was a pervasive “stench,’ due to urinals and toilets that were “broken, backed up, not cleaned and unsanitary.”

Some were so bad, he wrote, that if a kid attempted to actually use the urinal for its usual purpose, “fermented urine” would “splash back on their shoes and pants.”

When Martinez asked whose job it was to clean the toilets and urinals, he evidently got blank looks. “….No one knew,” he wrote.

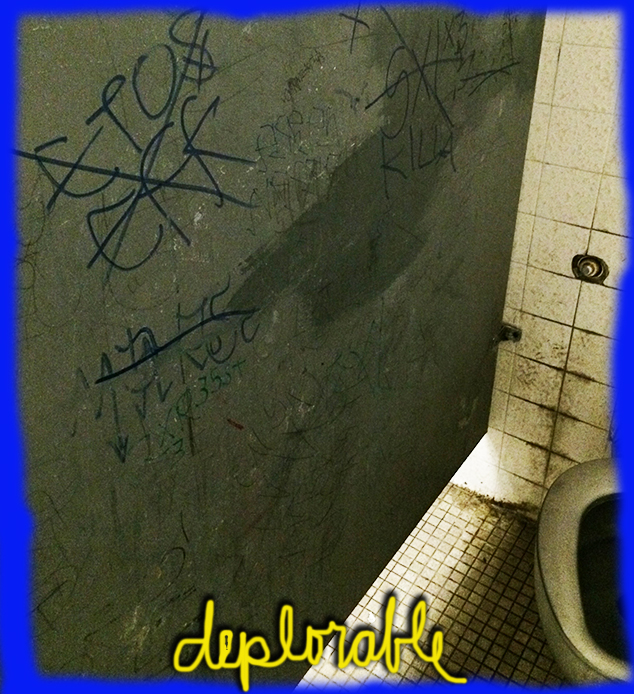

DOORSTOP BIBLES AND GANG GRAFFITI

And there were other issues, like the use of kids’ possessions as doorstops to keep some of the probationer’s rooms open in order to let air in, because of the aforementioned ghastly smell that permeated the unit because of the clogged toilets.

“Due to the unbearable stench,” wrote Martinez, “the doors to the rooms are propped open.” But the items used as doorstoppers were the belongings of the probationers. In one case, Martinez noted, the doorstopper was “a minor’s shoe.”

In another case, he wrote, the item on the floor holding open the door was a probationer’s Bible.

Several units of 14-15 boys per unit had no running water at all except in the staff bathrooms.

All 54 of the girls out of the 200 minors in the hall on Valentine’s Day didn’t get their scheduled activity for the day. Instead, according to Martinez’s report, the girls sat around for the activity period, while the staff talked among themselves.

The list goes on.

Martinez also found graffiti—in particular gang graffiti-–in the children’s units, rooms and bathrooms. When he asked staff about this and other issues, according to the report, the staff he spoke with either seemed to feel powerless to change anything, or “saw no problems,” or viewed the issues as “not part of my job.”

Martinez wrote of a “disconnect” between “administration and staff,” leaving the staff with low morale, “complacent,” and feeling “that there will be no accountability.”

“…It appears that no one cares,” Martinez wrote.

OTHER FACILITIES MANAGE TO DO THINGS RIGHT

In his report, Martinez made a point of praising some of the county’s other probation facilities for doing a consistently good job, including Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall, located in Sylmar, and Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall, located in Downey.

“Los Padrinos” he wrote, “has a daily graffiti inspection for both living rooms and bathrooms, and [the] rooms are spotless.”

Martinez also noted that not all the units at Central Juvenile Hall were in the same condition of filth and disrepair as those units that caused him such concern. Certain other units were clean and graffiti free.

So why were the bad units allowed to get so bad?

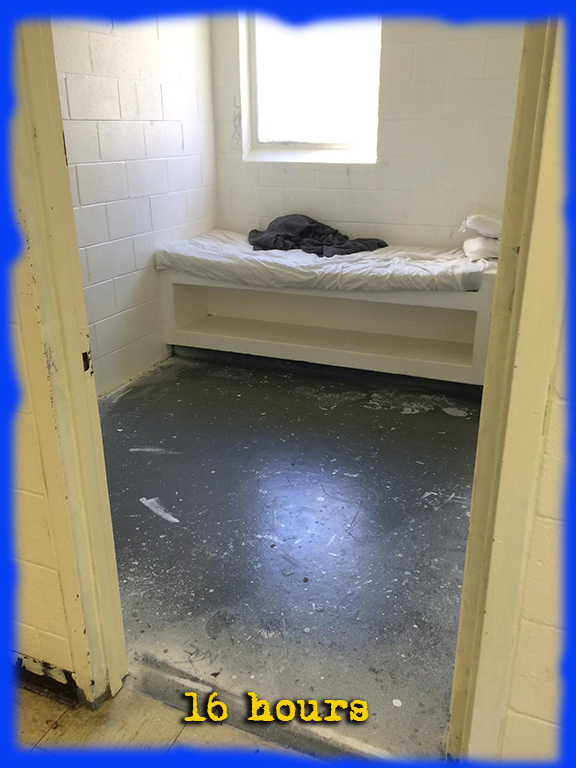

SOLITARY FOR 16 HOURS BECAUSE OF A FOOD TRADE

Another distressing part of Martinez’ Valentine’s Day report pertained to a boy who was sent for 16 hours to juvenile hall’s Special Housing Unit (SHU), which means solitary confinement. The boy’s offense was trading a carton of milk with another boy for a carton of orange juice—or vice versa.

Food trading with other kids is evidently against the rules. But, there are plenty of ways to appropriately sanction a boy who simply wants a little more of healthful beverage. Sixteen hours in solitary confinement is not one of them. Furthermore, it is against the department’s own rules—which are reportedly to send a kid to solitary for no more than a few hours as a time out, barring an exceptional situation. Martinez wrote that the juvenile hall director he spoke with about the matter admitted that he didn’t believe that the boy should have been sent to the SHU to begin with for such a trivial infraction. Yet, it appears that the boy might have been in isolation far longer than 16 hours, had Martinez not specifically asked for him to be sent back to his home unit.

Common sense suggests that, in all likelihood, if an abuse of solitary confinement for kids occurred during Martinez’ recent visit, it has also occurred in other instances. How many other instances, we have no way of knowing.

The truth is, any one of a number of mid and high level supervisors in the department could or should have walked through juvenile hall and seen these entirely unacceptable problems.

So why didn’t they?

Getting a plumber in to fix toilets and making sure gang graffiti is immediately removed from any wall or floor surfaces is hardly an impossible task.

And, when we have been assured that, in LA, the juvenile SHUs are not being used for prolonged isolation, why are we finding out due to Martinez’ surprise visit, that in fact the practice is still being wrongly used—and for the most preposterously trifling of infractions?

Certainly, there are many things going right in probation, including in juvenile probation. (And we’ll be running some articles on some of the success stories later this year.) But there is still a lot going wrong—especially on the juvenile side, as other reports we’ve covered here, here, and here have made clear.

For these reasons we are grateful to the dedication of probation commissioner Sal Martinez, for his willingness to go to bat for the kids who, as he wrote at the end of his report, “have no voice.”

Martinez, of course, was once one of those kids who spent time in the county’s juvenile halls and camps and felt he had no future—-until a dedicated and talented probation officer took the time to reach out to him and, he says, saved his life.

“I believe I got a second chance,” Martinez tells kids he meets in juvenile hall when he visits. And he wants to make sure they also get the help that they need to stay out of places like juvenile hall in the future.

“That’s why supervisor Solis appointed me.”

We’re very grateful that she did.

Now we wait to see what concrete change comes of Sal Martinez’ latest report.

This story contains numerous broken links.