CALIFORNIA PRISONER REALIGNMENT AND ITS SUCCESSFUL IMPLEMENTATION, WILL BE PART OF GOV. BROWN’S LEGACY

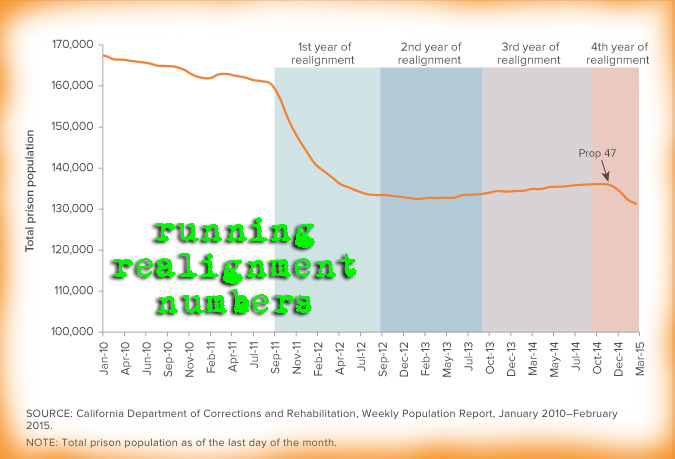

California’s prisoner realignment, which went into effect in October of 2011, shifted the incarceration burden for certain low-level offenders away from the CDCR (California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation) to the states’ 58 counties.

In 2013, the Public Policy Institute of California looked at what effect, if any, realignment had on crime in its first year of existence. It found a slight uptick in violent crime, but noted that it was comparable to similar increases in violent crime elsewhere in the country in states that had no new realignment strategy. (There was however, an anomalous uptick in auto theft, for which the researchers had no explanation.) At the same time, in that first year, the state’s prison population dropped by around 27,000 to 133,400 inmates.

On Tuesday, the Public Policy Institute of California released a second report, finding that in 2013, crime rates dropped several percentage points (or more) in all categories of violent crime and property crime calculated.

And, thanks to realignment, and more recently, Prop 47, the state’s prisons are now 2,200 inmates below the 137.5% capacity deadline set by a panel of federal judges. (Prop 47 reclassified certain non-violent drug and property-related felonies as misdemeanors.) County jail population growth has also slowed down.

A Sacramento Bee editorial lauds California Governor Jerry Brown’s criminal justice reform efforts, calling realignment an important accomplishment and a model for the nation.

UNDER-THE-RADAR CALIFORNIA “TRAILER BILL” WOULD CONCEAL RECORDS OF KIDS KILLED BY THEIR PARENTS’ SIGNIFICANT OTHERS…AND MORE – UPDATED

A “trailer bill” tucked away in the CA budget proposal would hide records of child deaths at the hands of a parent’s boyfriend or girlfriend. It would also limit access to other case notes, and keep social workers’ identities secret in such cases. Interestingly, the bill would also implement a federal order to release case files when kids are brought close to death.

Because the bill is attached to the budget, it will bypass the usual committee review process.

According to the Times, the bill could be voted on as early as today (Thursday).

The LA Times’ Garrett Therolf has more on the bill. Here are some clips:

…state and county officials implemented a battery of child protection reforms that child welfare advocates credit with reducing the number of children who die because of abuse and neglect.

But the bill currently under consideration would relax deadlines for the release of records, and keep the names of social workers secret. It would deny the public access to original case notes, instead providing abbreviated summaries of how the government attempted to protect vulnerable children.

It would also exclude the public from reviewing case files concerning children who were killed by their parents’ boyfriends or girlfriends.

[EDITOR’S UPDATE: We have just deleted a sentence in our clip from this LA Times story. It had to do with DCFS’s purported sponsoring of this worrisome bill, which—according to information we have subsequently received—turns out to be incorrect. (A DCFS spokesman said that those at his office first learned of the bill’s existence this morning from the LAT’s and WLA’s reporting. He assured me that DCFS is not at all in favor of the information-restricting proposed legislation.)

The Times too has removed the problematic sentence, although without notifying readers that they have done so. Instead the faulty information just unaccountably vanished. (Bad LAT, no cookie!)]

[SNIP]

Pete Cervinka, the deputy director of the social services department who reportedly led efforts to draft the rollback, declined to answer questions about the proposal.

A spokesman noted that the department had not yet publicly introduced the language of the bill, which he said will implement a federal mandate to release records for the first time in cases where children are injured to the point that they are “near death.”

DZHOKHAR TSARNAEV AND THE DEATH PENALTY, AS SEEN THROUGH THE EYES OF SOMEONE PAID TO HUMANIZE DEFENDANTS IN CAPITAL PUNISHMENT CASES

In a story for the Nation, Debbie Nathan, a journalist and freelance “mitigation specialist” for death penalty cases, gives an interesting take on Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s case from the eyes of someone whose job is to “de-monster the monsters.”

In death penalty cases, when guilt is already established, mitigation specialists dig through the defendant’s past to present a humanizing narrative that will sway jurors to spare the defendant’s life. Often, according to Nathan, the investigations turn up prior abuse, mental illness, and other traumas. But, Nathan says, the concepts and practices of mitigation investigations, vilification, and even innocence claims are indicative of a broken criminal justice system. Nathan argues that humans should be allowed to make bad decisions, even catastrophic ones, and remain among the living.

Here are some clips from Nathan’s insider take on the issue:

We search out hardship in early life. In death-penalty cases, this is usually like shooting into barrels of fish. Capital murder is an extreme behavioral outlier and almost always is associated with a gross inability to control one’s frustration, anger, and other antisocial impulses. The problem is most often associated with conditions like intellectual disability, mental illness, exposure to environmental and workplace toxins, and substance abuse. Learning this background can liberate a jury from simplistic and legalistic notions of “guilt,” toward the more complicated understanding that when terrible things happen to someone, even grotesquely violent responses are imbued with a quantum of moral innocence.

[SNIP]

Exposition. Rising action. A plot gone awry and a horrible climax. The denouement remains to be written. We mitigation specialists hope the poetics of our client’s life will move the jury to consider their own poetics. To think, as they lie in bed at night after court: “There but for the grace of God go I. Or my child!” They might vote to kill a monster, but not a human. Mitigation narratives don’t work all the time—witness what’s just happened with Tsarnaev. But they work often enough, and they save lives.

As a result of this work, I see capital cases from the inside. I see privy things. Very occasionally, I see strong evidence that someone is actually innocent: they seem truly to have done no wrong. These cases underscore the State’s outsized and often corrupt power, exercised though egomaniacal and dishonest district attorneys, lying cops, inept “experts.” These cases have become a powerful argument against the death penalty.

But I’ve also seen cases in which the defendant and his lawyers have publicly claimed innocence—yet during my work I’ve found evidence suggesting my client is guilty. I’ve seen attorneys hide the “bad facts” of the case—facts, kept quiet by the defense, which suggest that my client did commit murder. These are the moments in which I question the corrosive role that “innocence” plays in criminal justice, and in our effort to reform that broken system.

Claims of innocence can be tremendously useful tools. In court they can rout a death sentence, particularly when raised on appeal to contest an execution that is imminent. Politically, innocence claims are a potent argument against capital punishment, because who, even among the most die-hard of capital punishment advocates, wants to mistakenly execute the blameless?

But innocence claims, even in far lesser crimes than murder, can be as corrosive to our struggling comprehension of humanity as is the prosecutor’s rant about “monsters.” Handed down in courtrooms and in the court of public opinion, a judgment of innocence gives indigent people, people of color, and immigrants the right in America to live. But the other side of the shiny coin of innocence is the crumpled currency of guilt. You’re not innocent? You fucked up? Then you deserve your exile—prison for an eternity, ejection from the United States, your life injected away on a gurney. After all, you’re not innocent.

CROWDFUNDING FOR PEOPLE ALLEGEDLY ABUSED BY LAW ENFORCEMENT, WHO CANNOT AFFORD LEGAL FEES

Anoush Hakimi turned to crowdfunding to “level the legal playing field” by helping indigent victims of alleged police abuse pay their attorney’s fees.

KPCC’s Frank Stoltze has the unusual story. Here’s a clip:

The effort is designed to address a perennial problem in police abuse litigation: most victims are poor and their attorneys only get paid when there’s a settlement or a jury finds in their favor.

In the meantime, attorneys spend their own money to hire expert witnesses, conduct discovery and prepare the case.

“So naturally, plaintiff attorneys are reluctant to take on cases unless they are a slam dunk,” said Hakimi, 37, a Century City finance lawyer. “This leaves a lot of people out in the cold.”

Too often, he argued, victims are forced to settle a case on the cheap because their lawyers can’t afford to fight. The Iranian immigrant, who graduated from UCLA Law School, said he co-founded TrialFunder.com to raise investor money to bolster good cases.

Hakimi said investor money will “level the legal playing field” against deep-pocketed cities, counties and corporations.