Criminal justice system fees levied against people convicted of low-level offenses appear to have no deterrent effect and produce little fiscal gain for the government, while causing serious financial and legal problems for defendants, according to a new, first-of-its-kind study.

This latest study follows many previous reports that have looked at how justice system fines and fees disproportionately burden low-income people and their families.

The new study, published in the American Sociological Review, is different, however, in that it was the first to use a randomized trial to determine the impact of criminal legal system fees.

The research team, led by the late Harvard Professor of Sociology of Public Policy, Devah Pager, included Bruce Western, a sociology professor at Columbia University, and co-director of Columbia’s Justice Lab, Harvard PhD student Helen Ho, and Rebecca Goldstein, an assistant professor at Berkeley School of Law.

The team studied a group of 606 people convicted of misdemeanors in Oklahoma County, Oklahoma’s most populous county and home to the state capital.

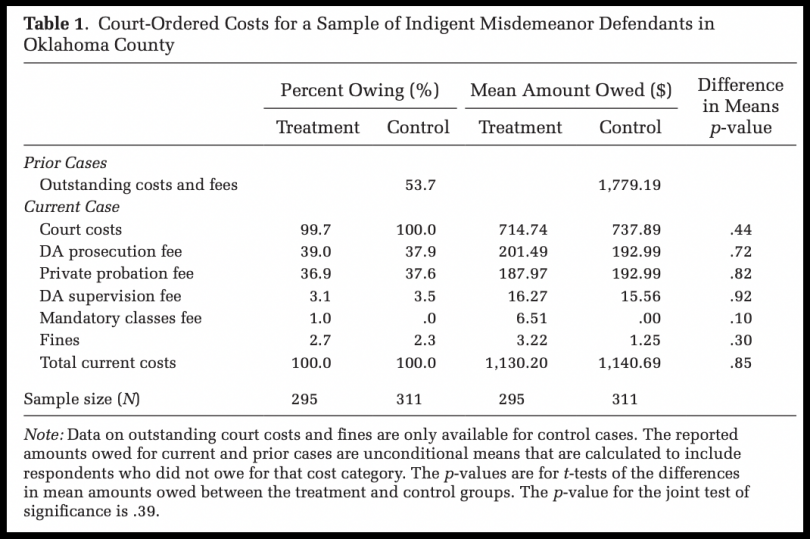

The researchers paid to wipe out the criminal justice debts, with the exception of restitution, of approximately half of the study’s participants. The rest were subjected to the county’s usual debt collection treatment.

The control group was saddled with an average of $2,920 in debts from past and current convictions. The debt accrual usually starts with an arrest warrant, which costs individuals $75.

Folks who go on probation typically pay $80 per month, half to a probation vendor and half to the DA’s office for the cost of prosecution.

And crimes with no apparent victim, like drug possession, are still subject to restitution fees.

Most defendants have no choice but to go on a payment plan to slowly chip away at the debt. When they miss payments, however, their debt is sent to a collection agency that heaps on an additional 30 percent.

The study found that imposing these fines and fees was not effective as a deterrent, as some tough-on-crime policymakers have argued. The treatment and control groups were rearrested, reincarcerated, and reconvicted at similar levels.

The difference, researchers saw, was that the treatment group was not subjected to debt collection efforts of the court system, had fewer warrants for nonpayment, were less likely to accrue new debt, and were more likely to keep their state tax refund, which, for the control group was often garnered to cover unpaid debts.

“Court obligations for fines and fees are less painful than incarceration, but they are intrusive and create the risk of more serious punishment,” the researchers wrote.

“In Oklahoma County, the misdemeanor court processed drug, public order, and other low-level offenses for people who experienced high levels of poverty, unemployment, homelessness, and poor health,” the report stated. “Intercepted tax refunds and debt collector pressure can add to the economic insecurity of poor defendants, and warrants place them at risk of arrest and incarceration.”

(While Oklahoma County did not incarcerate people for failing to pay their debts, as a rule, this is not the case in many other jurisdictions.)

One of the primary purposes of imposing the fees was to fund the local justice system. Over a year period, however, the Oklahoma County court system only claimed five percent of debt owed.

Here in Los Angeles County, the government recouped an even smaller percentage of court debts, research showed.

On February 18, 2020, the LA County Board of Supervisors voted to eliminate dozens of criminal justice system fines and fees.

The supervisors directed LA County Probation and other relevant departments to stop collecting the fines and fees over which the county has jurisdiction. All outstanding debt was canceled.

The decision appeared to be an easy one for the supervisors who had information from two reports, a county report and a study from a coalition of community organizations, Let’s Get Free LA, that showed LA was collecting just 4 percent of more than $100 million in court debts, while expending a “significant amount of resources” to — unsuccessfully — collect those debts.

San Francisco, too, had eliminated locally imposed fines and fees by 2018. Yet, there were still approximately 80 state-level criminal legal system fees still impacting people in LA and SF, and across California.

In September 2020, the state took a first step to address the issue with a bill, AB 1869, to dump 23 of the justice system’s administrative fees including costs of supervision, house arrest programs, and work release programs. The passage of AB 1869 discharged a colossal $16 billion in debt Californians owed for justice system involvement.

The state eliminated 17 more fines and fees via AB 177, which went into effect on January 1, 2022. The bill eliminated jurisdictions’ ability to collect those fees, and required unpaid debts to be wiped away.

Among those fees were a $25 administrative screening fee levied against people arrested and released on their own recognizance, and a $10 citation processing fee for those cited and released. Drug testing fees, and drug diversion fees were also eliminated.

The bill eliminated approximately $534 million in debt.

Still, many fees remain in California, including a $300 civil assessment charged to people unable to pay their justice system debts, or who miss a traffic court date.