Prison systems in at least 14 states take all incoming mail and scan it before giving incarcerated recipients photocopies — of letters, cards, drawings from their children, and any other personal mail sent from friends and loved ones — and destroying the originals, according to a report from Prison Policy Initiative (PPI).

Things like packages, magazines, newspapers, and letters containing money are returned to their senders. All the scanned paper mail goes into a digital database searchable by prison staff.

“This practice of mail scanning, either performed at the prison itself or off-site using a third-party vendor, strips away the privacy and the sentimentality of mail, which is often the least expensive and most-used form of communication between incarcerated people and their loved ones,” writes PPI research analyst Leah Wang.

The use of mail scanning appears to be spreading. Several more states and the federal prison system are also using mail scanning in some, but not all, facilities.

While California’s prison system does not swap out personal mail for scanned copies, PPI came across a mail scanning policy in Marin County’s jails.

Additionally, in a comment, a PPI reader said Tuolumne County also scanned mail sent to jails. The commenter said she had to send her letters all the way to Florida, so they could be scanned for her boyfriend in Tuolumne County jail to read on a kiosk. “I stopped sending letters because — what’s the point?” she wrote. “If there’s nothing tangible for him to hold and be able to read and re-read when he wants, I might as well just send him [an electronic] message to read on the kiosk.”

Sending mail to a digitizing middle man often means that mail is seriously delayed. And private companies bundle mail scanning with emails, digital greeting cards, and video call products that are far more expensive for families than sending paper mail to their loved ones in lockup.

“Scanning mail pushes incarcerated people to use other, paid communications services provided by the companies,” Wang writes. “Compared to mail that’s delayed due to scanning procedures, or scanned incorrectly, incarcerated people and their loved ones often understandably switch to electronic messaging (which requires the purchase of digital stamps), phone calls, or video calls.”

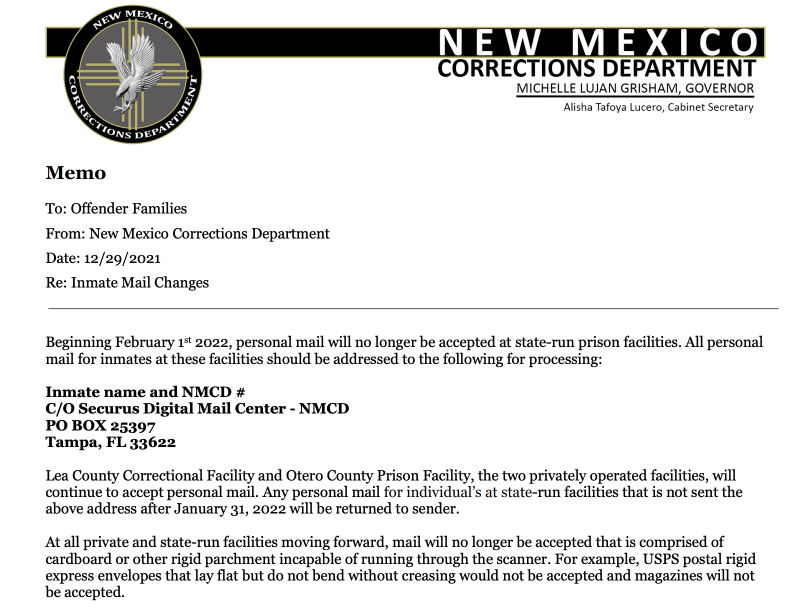

Securus Technologies, one of the primary private companies offering digital mail processing, markets its product as one that frees up prison staff from having to search through incoming correspondence. The service also “dramatically improves investigative intelligence,” and “provides immediate notifications to staff and investigators when particular incarcerated individuals receive mail,” according to Securus.

Another company, Smart Communications, boasted that its staff would have access to senders’ email addresses, physical addresses, IP addresses, phone numbers, GPS locations, and the exact devices people used to access the Smart Communications system. It’s not hard to imagine how this might deter people from sending personal mail to people in prisons and jails.

And, perhaps the most popular claim drawing corrections systems to outsource and digitize mail handling is that the service will reduce the amount of drugs that enter prisons through the mail.

Prison and jail administrators have long pointed to physical mail and visits from friends and family as the primary way drugs enter lockups.

Yet, during the pandemic, when Texas prisons restricted in-person visits and mail people in prison were caught with drugs more frequently than before. The same thing happened when New York City banned visits during the pandemic. Instances of drug seizures drastically increased during several months between April 2020 and May 2021, but data shows that mail accounted for less than a third of the seized drugs.

An analysis by PPI also suggests that correctional officers and prison staff are more likely responsible for the majority of the drugs that get into the hands of incarcerated people.

In July 2021, a coalition of organizations led by Just Detention sent a letter to U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland demanding the federal Bureau of Prisons end the mail scanning program it was piloting at two prisons.

“Banning physical mail harms the well-being of incarcerated people, while offering no meaningful benefits,” the coalition’s 2021 letter read. “Yet despite MailGuard’s flaws, BOP is in no hurry to cancel it; in fact, the agency has signaled that it may expand the program to additional facilities. At the same time, state departments of correction and county jails are rolling out similar mail restrictions; if the federal government continues to endorse MailGuard, more jurisdictions are likely to follow suit.”

Since then, according to PPI, the feds have expanded their use of Smart Communications’ mail photocopying service, MailGuard, setting it up at most federal prisons, signaling the desirability of mail scanning to prisons and jails across the nation.