EDITOR’S NOTE: Our friends at the Chronicle of Social Change have launched a series on a concept in the juvenile justice world called Positive Youth Justice. This is a strategy that helps kids who have landed in the system build on their strengths in order to create constructive pathways to reconnect with family, school, and community life—and, in so doing, to redefine their own futures.

We’re happy to say we will be publishing several chapters from their series here at WitnessLA.

In the first chapter, CSC looked at a program in Olympia, Washington that works to keep kids out of the juvenile justice system.

This week, they’ve profiled a program in Oakland, Calif., that uses a “community conferencing” model to mediate between juvenile offenders and their victims in such a way that promotes healing for both.

To find out more, read on!

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE: WHEN KIDS MAKE AMENDS TO THEIR VICTIMS

by John Kelly

HOW IT ALL STARTED

Restorative justice is a term that describes strategies in which offenders make amends directly to victims. Community conferencing is one type of restorative justice strategy, and it traces its origins to New Zealand.

It emerged in the late 1980s as a juvenile justice medium when New Zealand officials got serious about addressing the disproportionately high involvement of Maori youth in the system. Conferences have lowered the number of Maori youth who end up in court and sent to foster care as a result of delinquency.

“It’s not just a quirk of New Zealand,” said Liz Ryan, CEO of Youth First!, a nonprofit that advocates to reduce the use of incarceration in the juvenile justice system.

Ryan said conferencing was a frequently discussed topic at the World Congress on Juvenile Justice, held last month in Geneva, Switzerland. “[Restorative justice conferencing] is being replicated all over the world, and people are particularly discussing it in terms of racial and ethnic disparities.”

Pennsylvania native sujatha baliga (she does not capitalize her name) is the primary reason that community conferencing has gained a foothold in Alameda County. She moved to California in 2006 to do appellate work on death penalty cases after serving as a public defender in New York City.

In 2008 she received a Soros Justice Fellowship and used the time it afforded her to develop a community conferencing presence in Oakland. Her program started at Restorative Justice for Oakland’s Youth; when funding issues challenged the organization in 2010, she moved the conferencing program to another nonprofit organization called Community Works.

In 2011, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation awarded Community Works $1.05 million in federal block grant funding to divert “at least” 95 juveniles per year.

At the same time, the National Council on Crime and Delinquency (NCCD) hired baliga to lead its national restorative justice program.

THE PRACTITIONERS

Baliga now oversees the training of conference facilitators for Oakland, and she has also taught Oakland police officers how the program works.

In addition, she and Program Associate Nuri Nusrat lead NCCD’s technical assistance to other sites that are interested in importing their Oakland model. For example, in 2013 the Zellerbach Family Foundation funded a replication of the community conferencing program in San Francisco.

Yejide Ankobia, a veteran restorative justice practitioner in the Bay Area, serves as Community Works’ program manager for the conferencing program. She leads a staff of four facilitators and one administrative assistant.

THE SYSTEM

Youth are diverted to Community Works by the police or a prosecutor. Someone on staff will pursue the conferencing option with the youth and his or her parents.

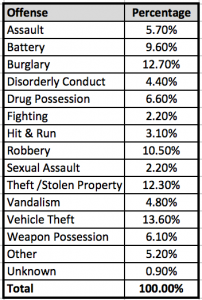

Among the offenses for which youth are frequently diverted to conferencing: burglary, robbery and vehicle theft (see table).

A member of the Community Works conferencing team will make the initial outreach to youth who are recommended for diversion.

“One of the first things we tell them is, ‘Nothing you say to me can be used against you; we really don’t want you to catch a case,’” said baliga.

She recalls one early diversion in which two teens were arrested while attempting to break into a home in their neighborhood. A screen had been ripped open and a window had been damaged before the next-door neighbor called the police.

Baliga met individually with the two youths, and then together with their parents, to discuss what had happened. She established the answers to questions that she knew the victim would have: Which one cut my screen? Whose idea was it? She then had each write a letter of apology.

Initial meetings like this help conferencing staff establish whether or not the youth is amenable to the process. If they are not, the case is diverted back to the system. At this point, for the conferencing to move forward, Community Works must get buy-in from the victim.

In the case of these two teens, baliga called the victim with a standard initial message.

“I told her I was sorry this happened to you, that we want to help make it right and that this process is about making it right,” she said. Another thing stressed right off: “There is absolutely no pressure to participate.”

Baliga said that in her career as a conference facilitator, she has only once had a victim say they did not want the youth to be processed through a restorative justice alternative. There are plenty of instances, however, in which victims agree to the process but choose a surrogate to participate in the conferencing.

The victim agreed to attend the conference in the case of the two teens who attempted to burglarize her house, so a conferencing session was scheduled at a nearby community center. The time and date are always at the discretion of the victim.

There is no hard limit on the number of attendees to a community conferencing session, but there is a minimum:

*The youth or youths must be there in person.

*A supporter for the youth. This can be a parent, but that is not always the case. Baliga said there are plenty of instances where youth pursue the conferencing option while their parents favor formal processing.

*The victim, or a surrogate for the victim.

*If the victim attends, a supporter from the community must accompany him or her.

*At least one trained conferencing facilitator.In this case, the two teens were accompanied by their parents and the victim was accompanied by the neighbor who had called about the break-in.

The Oakland model, which draws directly from the one used in New Zealand, begins with an opening statement by the youth and a review of the ground rules by the facilitator.

This is followed by a statement from the victim about what happened and how he or she was affected. Next comes the youth, who explains in detail what happened.

At this point, the victim is allowed to ask questions of the offending youth. After that, other members of the circle are invited to discuss the crime that took place and its impact.

Baliga said the conversation inevitably “shifts toward what needs to happen, and that’s when I’ll call a pause.” The youth and their supporters will step out of the room and discuss a plan.

The plan is required to demonstrate how the youth will do right by the victim, his family, his community and himself. The goals must follow what the program has dubbed the “SMART” rules: specific, measurable, attainable, related and timely.

The victim always has final say on what amounts to fair restitution, baliga said, and the juvenile is obliged to either object to or accept those terms. Agreement on restitution is the final piece.

Sometimes the agreements are monetary, baliga said, and are quid pro quo. In the case of the two teens, they worked at the automotive shop of a relative until they had made enough to repair the victim’s window. The teens also committed to regularly attending football practice, and raising their grades from a D average to a C in the next semester.

Another victim whose fence was burned down had the youth build a new one with a carpenter.

Other victim requests “you never see coming,” baliga said. One victim, whose car was damaged in a string of car thefts, asked the young perpetrator to create a five-foot tall painting of Tinker Bell from Peter Pan.

“The Tinker Bell person was a twenty-something [civilian] employee of the police department,” baliga said.

The facilitator asks the youth what help they need achieving the goals, and secures commitments from adult supporters that they will assist in those aspects of the plan.

Once a plan is finished, Community Works holds a “completion ceremony.” It is a way to acknowledge that the youth has made the transition from being responsible for a crime to being a responsible member of the community, baliga said.

REVERSE MIRANDA

The conferencing process asks kids to be scrupulously candid about what they have done. With this in mind, early on in the development of the program, baliga secured a guarantee from prosecutors, a “reverse Miranda” that enables conference participants to discuss any topic freely.

The term, of course, refers to the traditional “Miranda rights” warning administered by police to those they arrest, advising them that anything they say can be used against them.

In the Oakland program the classic warning is flipped on its head; anything that the juvenile says during the conferencing process cannot be used to prosecute them at any time, for any offense.

Baliga persuaded the district attorney’s office to agree to the blanket immunity.

“They come clean about all kinds of stuff,” baliga said. The risk involved in this informal immunity is minimal because conceding guilt for an offense is price of admission to a conferencing diversion.

“Law enforcement has reason to love it, because kids confess,” baliga said. “They say sorry, they cry, and commit to working on improving their lives. The system doesn’t give much opportunity for district attorneys to ever really see remorse.”

BUT DOES IT WORK?

So far, 102 youths have participated in a conferencing session and completed the proposed plan. Of those youths, 11.8 percent have been adjudicated again; meaning they were arrested, a petition was filed against them and it was sustained.

A matched comparative sample of youth whose cases were processed through the system yielded a 31.4 percent re-adjudication rate.

WILL OAKLAND PAY FOR SUCCESS?

Baliga believes that the program could one day be used to handle any juvenile offense, including a homicide. In the short term, though, she would just settle for it surviving another year.

The federal grant to Community Works runs out in June, which could mean the end of the program unless the city, county or state supports it.

One potential strategy is a pay-for-success (PFS) agreement, which has been proposed to Alameda County by NCCD. Under the agreement, private funding would pay for a large expansion of the community conferencing program, perhaps up to 400 cases per year.

The county would then pay for the services only if certain agreed-upon benchmarks around recidivism were achieved. If the program has little impact, the county spends nothing.

“We are trying to get the county on board for the PFS thing,” baliga said. “Our program costs about $5,000 per kid in total, and it’s $22,000 per year for probation.”

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE & HOMICIDES

In her first month at NCCD, baliga facilitated a community conference in Florida, one of the most punitive states in the nation. The case involving a 19-year-old named Conor McBride, who in 2010 shot and killed his 19-year-old fiancé Ann Grosmaire. Both were 19 at the time. An hour after the shooting, McBride walked into the Tallahassee Police Department and turned himself in.

(Click here to read a long, narrative piece about the case by Paul Tullis for the New York Times Magazine.)

In the end, the conference restitution includes McBride’s lifelong commitment to volunteer at a long list of places where Ann’s parents believe she would have wanted to help.

And instead of a life sentence without the possibility of parole, McBride received a 20-year sentence.

Baliga said she believes that the McBride case proves there is no ceiling on community conferencing as a strategy; that any offense — even murder — can be mediated, at any point along the judicial route, as long as there is a willing victim, or as in this case, the victim’s family, and an offender who is willing to go through the process of fully confronting what he or she has done.

“My hope is that we are able to move there, especially if it’s victim-initiated,” baliga said. “If it can happen in Florida, why not anywhere else?”

John Kelly is editor of The Chronicle of Social Change.