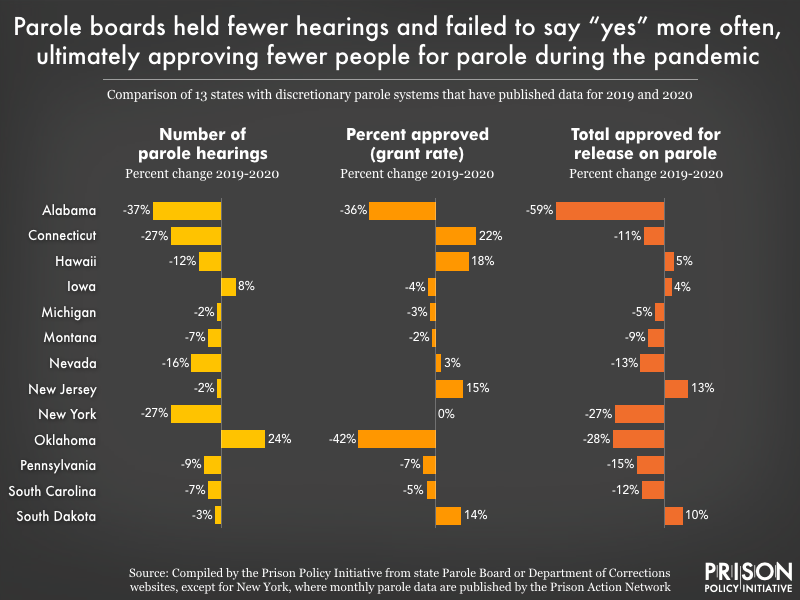

Only five out of 13 states actually increased the number of people granted parole during the first year of the pandemic over 2019, as COVID-19 raged through prisons and jails, infecting and killing incarcerated people and employees, data analysis by the Prison Policy Initiative revealed.

“Denying people parole during a pandemic only serves to further the spread of the virus both inside and outside of prisons,” PPI Research Associate Tiana Herring wrote in the report. “Parole boards still have the opportunity to help slow the spread of the virus by releasing more people in 2021.”

Out of 34 states where discretionary parole decisions are made, PPI found usable data for 2019 and 2020 for 13 states: Alabama, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and South Dakota.

Eight of those states — Alabama, Iowa, Michigan, Montana, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina — either experienced decreases in parole approvals or no change. Alabama, Hawaii, Iowa, and New Jersey report their parole data by the fiscal year instead of the calendar year, so in those states “the impact of the pandemic on parole releases may appear less extreme.”

California is not among the 13 states PPI examined for the report, but state data shows that the state’s parole board approved just 49 more applications for parole in 2020 than it did in 2019.

While more people went before the CA parole board last year, the board’s parole approvals made up a smaller portion of the overall cases heard in 2020 than during the previous year.

In 2019, the parole board heard 6,061 cases and granted parole in 1,184 instances (19.5 percent), while denying 2,257 people (37 percent).

There are other parole hearing outcomes, including instances in which people voluntarily waive their parole hearings, or have their hearings postponed.

In 2020, the board heard 7,684 cases and approved 1,233 people (14.6 percent) for release on parole. A total of 2,227 (29 percent) were outright denial decisions. Thirty-four percent of hearings were postponed in 2020, up from 20 percent in 2019.

“Granting parole to more people should be an obvious decarceration tool for correctional systems, during both the pandemic and more ordinary times,” Herring wrote. “Since parole is a preexisting system, it can be used to reduce prison populations without requiring any new laws, executive orders, or commutations. And since anyone going before the parole board has already completed their court-ordered minimum sentences, it would make sense for boards to operate with a presumption of release.”

Yet parole boards are generally far more likely to deny people parole than to return them to their communities, pandemic or not.