CA LAWMAKERS UNANIMOUSLY PASS BILL TO MODERNIZE AND SPEED UP THE WAY CRIMINAL JUSTICE-RELATED IS REPORTED TO THE PUBLIC

On Tuesday, the California Assembly passed AB 2524, a bill that would change annual criminal justice summary reports published by the state Attorney General’s Office into incident-based digital data sets to be published on Attorney General Kamala Harris’ OpenJustice website. AG Harris praised both the Senate and Assembly for unanimously passing the bill to “bring criminal justice data reporting into the 21st Century.”

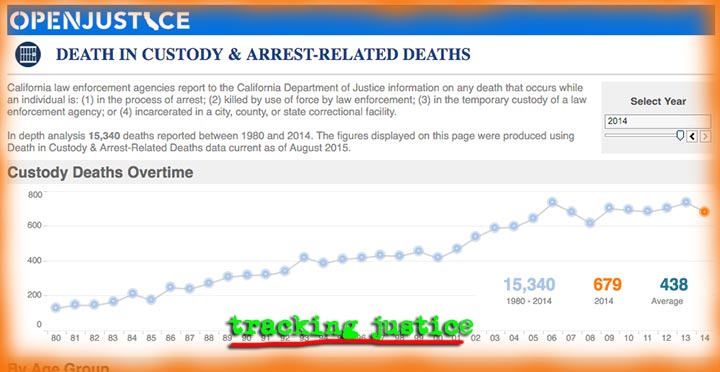

Last September, AG Harris launched the OpenJustice site to bring transparency to the state’s justice system by publishing crime and policing statistics. The website shows city, county, and state crime and arrest rates, deaths during arrest, deaths in custody, and the number of law enforcement officers killed or assaulted. Users can view data on interactive maps and graphs, and sort data groups by race, gender, and age.

The bill, introduced by Harris and Assembly Member Jacqui Irwin (D-Thousand Oaks), would also require the DOJ to work toward implementing a smoother, all-electronic collection of criminal justice data that would be updated on the OpenJustice site at least every quarter, rather than on an annual basis.

“…Only approximately 40% of local law enforcement agencies currently submit required data sets through electronic means, impeding the ability of the state to implement a uniform reporting structure through which information is made available to the public more frequently and more effectively,” the bill reads.

AB 2524 now moves to Governor Jerry Brown for final approval.

LENORE ANDERSON ON HER TEENAGE YEARS, CRIME VICTIMS’ VOICES, CRIME RATES, AND MORE

In an interview with the Huffington Post’s Nico Pitney, Lenore Anderson discusses her own personal journey from troubled teen punk rock drummer to big-time attorney and founder of Californians for Safety and Justice—the group behind CA’s Proposition 47. (If you’re unfamiliar, Prop. 47 downgraded six non-serious drug and property-related felonies to misdemeanors.)

Anderson tells the story of the transformative moment she realized that all the help and guidance she received during her teenage years from teachers and police—even as lawmakers pumped out tough-on-crime laws and laws born from fear of the juvenile “superpredator”—was an exclusive benefit of her white privilege.

Here’s a clip from the interview:

I was a troublemaker as a kid. I got in trouble with neighbors, parents, police, teachers, and it wasn’t until I was older that I understood that the help that was offered me is not the help that is offered to kids of color in my exact same position. In realizing that, I made a commitment to work on racial equity and criminal justice reform for my career.

I was in California in the 80s. During the exact same time that I was in high school, the number of tough-on-crime laws that were being passed in the legislature, the number of laws that were focused on the juvenile predator ― that was when it was occurring. And at that same time, I’m in high school ― middle-class white female ― doing things that are not that different from what a lot of young kids of color would be doing at that time in their lives, and the response to me was one of forgiveness.

Police would take me home instead of taking me to juvenile hall; my parents had resources to get me counseling and therapy; teachers let me pass classes that I didn’t actually pass. There was a perception that what I was doing were cries for help, and we need to figure out how to help her get on the right path; to see me as one that needed to be protected through my juvenile confusion to adulthood.

Fast-forward ten years and I’m talking to parents of incarcerated youth. These are young people whose stories are not that markedly different from mine, with the exception of the response ― the exception of what police did, what parents had resources to do, what teachers did. I think that’s really why I do the work I do.

I didn’t go straight to college after high school. Eventually I went to junior college, mainly because I needed health insurance, and I enjoyed it. I did really well and ended up at UC Berkeley, and there I was very much interested in social justice. I go to an event where one of the speakers is Cornelius Hall, whose son Jerrold Hall was shot in the back by a law enforcement officer working for BART [the Bay Area’s rapid transit system] upon suspicion that he had stolen a Walkman.

That was a pivotal moment for me because, you know, half my friends stole Walkmans. No doubt, no question, I was one of the many teenagers who could have been Jerrold Hall, with the difference being he’s an African-American male and I’m a white female. I think that was one of the key moments where I was clear on the privilege that I had benefitted from.

Anderson also talks about the often overlooked perspective of crime victims and changes they would like to see in the criminal justice system. Californians for Safety and Justice conducted a first-of-it’s-kind national survey of crime victims’ views on criminal justice, which revealed that while 25% of crime victims are in favor of locking people away for as long as possible, an astounding 61% of victims are in favor of shorter sentences and a focus on prevention and rehabilitation.

The common assumption is that crime victims want vengeance, or that they want the toughest possible longest sentence. What we found is actually quite different.

We found that the majority of crime victims want rehabilitation over punishment. The majority of crime victims want shorter sentences and prevention spending over long sentences. We found the majority of crime victims think that prosecutors should spend more time focused on neighborhood problem solving and rehabilitation, even if it means fewer convictions ― even if it means fewer convictions. Those kinds of findings really stand out, and these are diverse crime victims from all backgrounds across the country.

There are enough people at this point that have had direct personal experience with the failings of our current approach to criminal justice that pretty much everybody agrees that most people get worse in prison, not better. How can that possibly be a good investment? Hearing that from victims I think is a really powerful intervention on the conversation on what we should be doing.

Be sure to go over to the Huffington Post and read the rest of Anderson’s interview.