Is Electronic Monitoring for Kids Just a Fast Trip to Lock-Up?

Sam* was 16 when he was arrested in Alameda County for stealing two pairs of sneakers from a department store. The arrest for the theft was his second in less than a month. Both of the arrests involved low-level misdemeanors. When he went before a judge, Sam admitted to one of the misdemeanor charges, but not the other, and he was placed on formal probation. One of the conditions of Sam’s probation was the requirement to wear an electronic monitoring device on his ankle.

The ankle monitor seemed, on the surface of it, to be a good idea. Unlike the worst old days of California’s state and county juvenile justice systems, instead of being sent to a locked juvenile camp or hall, in 49 of the state’s 56 counties, kids like Sam are often placed on home supervision with an electronic monitoring device.

Yet, a new report by the Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic at UC Berkeley School of Law; and the East Bay Community Law Center (EBCLC), has discovered that rather than being rehabilitative and constructive for a youth, electronic monitoring very often sets kids up for failure.

According to Kate Weisburd, a supervising attorney at the East Bay Community Law Center, which co-authored the report, Sam’s case is an all-too-typical example.

Sam had learning disabilities of a nature that made him a kid that often needed to “get some air,” said Weisburd. So he’d leave his house for short periods to, say, walk his dog. Yet, if Sam walked the dog after his curfew then suddenly he had violated the conditions of his agreement, which landed him in juvenile hall. (Most California counties reportedly have curfews of 7 or 8 p.m. for youth on electronic monitoring.)

The curfew agreement was only one of more than two-dozen rules that Sam had to remember and follow. For instance, he had to charge the device every night from 7 p.m. to 9 p.m. He had to remain in his house, except when he attended school. Any other movement outside of the house—going to work, to church, to the grocery store, or taking the dog out for a walk—had to be approved at least 48 hours in advance. Sam was also told to call the electronic monitoring office at least three times a day.

It didn’t help that Sam’s sole parent was a single working mother struggling to support three children. So Sam’s restrictions wreaked havoc with her work life, and the rest of the family’s home life. In addition, Sam’s mother was billed $15 per day by Alameda County for the device. She was also required to buy Sam a cell phone, which he had not previously owned. She did her best to plan any changes to the family’s schedule 48 hours in advance, and aimed to be home every day at exactly 7 p.m. so that Sam could charge the device. But, with her work, her responsibilities to her other kids, the vagaries of traffic, and more, both those marks were sometimes very difficult to hit, said Weisburd.

Matters were exacerbated by the fact that staying inside their small, cramped apartment all day, every day—-especially on days when there was no school—-was almost impossible for 16-year-old Sam.

Despite everyone’s best intentions, on two separate nights, Sam stayed out past 7 p.m. One of those times he was walking the dog. Another time he was nearby talking to kids in in the family’s apartment complex. Because of those two violations of the rules, a judge placed him in custody for three days.

Custody was, of course, what the GPS ankle monitor was supposed to avoid.

Yet, by the time Sam got out from under his nearly a year and a half of supervision by Alameda County’s juvenile justice system, he had been locked up in juvenile hall ten different times for similarly minor monitoring or probation violations. In total, according to Weisburd, Sam was detained in juvenile hall for three and a half months, including Christmas and his birthday.

“What’s remarkable about stories like Sam’s, is how ordinary they are.” said Weisburd.

The Fast Growth of Electronic Monitoring in Juvenile Probation

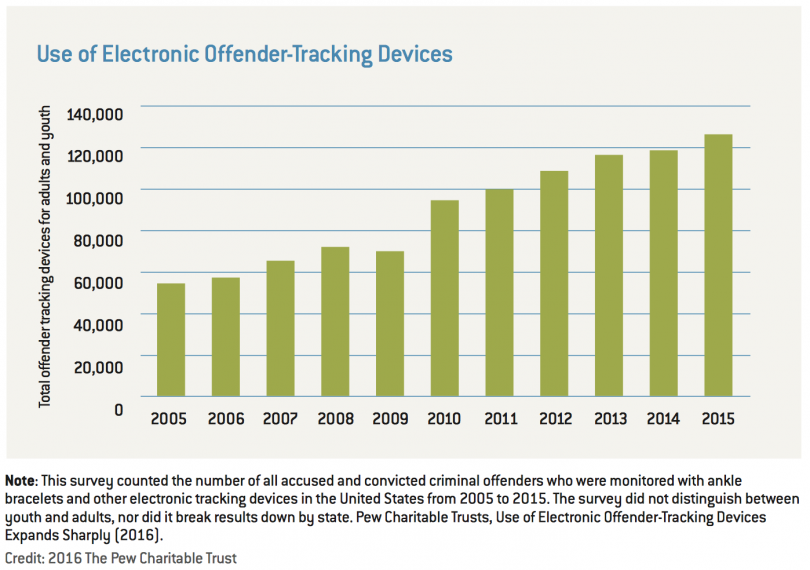

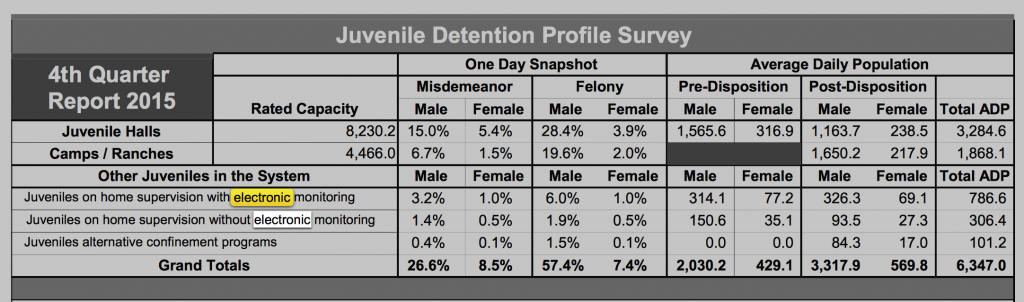

According to the new report, the use of electronic monitoring for kids has approximately doubled in the U.S. in the last decade. Every state but New Hampshire uses it. And, according to the latest report from the California’s Board of State and Community Corrections, on an average day, California has a minimum of 787 kids on electronic monitoring, and Los Angeles County has somewhere north of 400 kids. (The state’s total is likely higher, since not all the counties using the strategy report their numbers to the state.)

Yet, although there is an increasing trend to use only youth justice methods that are backed by research, the report’s authors say that there has been little or no research that examines juvenile electronic monitoring to measure whether or not it is effective, or if it has deeplyproblematic downsides that need to be examined and addressed, if it is to be used further.

“Without access to evidence-based program data,” the researchers wrote, “judges and policy-makers are unable to evaluate whether there are rehabilitative effects to these programs or whether these programs are excessively punitive.”

One of the problems the authors pointed to is the fact “there are no standardized protocols for the practice.” When the researchers examined information from California’s 49 counties that use the method, they found that the written program rules often varied wildly from county to county, with some counties requiring the monitored youth to follow eight special rules, while one county slapped the monitored teens with 58 rules. Most counties fell somewhere in between.

Yet no county seemed to have any research to back-up whether the various rules and regulations were effective. Moreover many of the regulations tended to cut against kids from lower income families, and families of color.

For instance, one California county instructs probation officers to “consider ‘the trustworthiness’” of the youth’s parents or guardian or approved caregivers “to monitor and report the minor’s behavior in the home” when deciding whether or not the kid was eligible for electronic monitoring. Another county tells probation officers responding to an electronic monitoring violation to consider the “background of youth” when determining what sanction to impose.

“These considerations,” wrote the report’s authors “are subjective and prone to racial bias.”

Some counties impose conditions that seem to serve no rehabilitative or instructive purpose, either for helping the youth, or increasing public safety. Instead the rules seem to be intrusive regulations that are merely punitive.

For example, “Ventura County,” the authors note, “requires that youth will ‘not cut [their] hair below a #2 clip (including fades).”

Mariposa County, “requires that youth agree to keep their ‘residence maintained in a clean and sanitary manner’ while they are on electronic monitoring.” The county also warns that “failure to maintain a clean home could result in removal from the program.” Never mind that a home with multiple children and a single parent with a difficult work schedule may result in clutter that is beyond a single teenager’s control.

A Program With Uneven Consequences

Like the uneven, un-researched rules, the consequences for a teenager who breaks one or more of the rules, also vary widely from county to county, according to the report.

“For example,” wrote the report’s authors, “Glenn County provides a progressive discipline grid for youth who violate electronic monitoring rules, with consequences ranging from counseling or writing an essay to the arrest and detention of the youth. The County also provides that ‘the least restrictive consequences required to change the behavior should be employed.”

Other counties resort to locking the kid up for minor infractions, as was the case with Sam. Certain counties leave the response to a violation up to the judgment of the probation officer, who may be either lax or overly strict.

“The problem is, rather than deterring youth from making poor decisions, a lot of electronic monitoring simply confirms what we already know about adolescent behavior,” Weisburd said.

“Youth make impulsive, peer-driven decisions that are often not in their long-term best interest. Electronic monitoring does not, because it cannot, change these immutable characteristics of adolescents. Electronic monitoring, without more research, does little other than expose youth to more punishment for typical adolescent behavior.”

Stories like Sam’s are by no means outliers, according to Weisburd. “If you go to juvenile court and talk to the families in the court hallways, you’ll hear a lot of stories that are very similar to the ones I tell about kids.”

She told WitnessLA of another kid, a 13-year-old client who was put on probation for attempting to steal a backpack. He admitted to the deed and pled to a misdemeanor, she said. “But he didn’t do very well on electronic monitoring, because the rules were so stringent.” Like Sam, the only time the 13-year-old could leave home was to go to school. “This meant he couldn’t stay for after school activities like sports without pre-approval.”

And approval, she said, due to the slow turning of the bureaucratic wheels, was not easy to get. “For instance, it wasn’t always clear whether he needed to talk to his probation officer or his, separate GPS officer for the approval. And when you leave a message, often they didn’t call you back.” In addition, the bureaucratic right hand, according to Weisburd, often didn’t know what the left was doing. “Sometimes his probation officer would say yes” to an out-of-the-house excursion,” and then the GPS officer would say that he never heard about it.”

It didn’t help that her client has ADHD, and so, like Sam, “it was really hard for him to stay inside all the time.” So he would violate the rules in small technical ways. “And every time he messed up on GPS he went back in to juvenile hall. Then he’d start over on GPS.” So monitoring wasn’t so much used as a substitute for custody, she said, “it was an add-on.”

Yet, the rhetoric around electronic monitoring, Weisburd told us, is generally upbeat. “They say ‘It’s rehabilitative,’ and ‘it’s a custody alternative.’ But, according to the report’s authors and Weisburd, the excessive rules often lead a kid straight to custody, without any real rehabilitation taking place in the process. Never mind that keeping kids out of custody is the theoretical raison d’être for GPS monitoring in the first place.

And There Are Privacy Concerns

Both the report and Weisburd also mentioned privacy concerns with the monitoring programs, particularly in certain counties.

The report’s authors cite, as an example, San Francisco County’s terms and conditions, which provide that “all information collected during [the youth’s] participation on the program may be turned over to anyone with a legal right or need to know.” This mostly means law enforcement agencies, courts and probation or parole agencies.

The researchers were particularly concerned about what for profit companies might do with the data gathered. For example, Alameda County, they said, contracts with a private electronic monitoring company that provides GPS equipment and tracking services, and is required to implement “a method of archiving recorded calls and/or reports for a minimum of seven years”

This means that “private companies are collecting huge amounts of data on a huge number of children,” said Weisburd. “And we don’t know what is being done with that data.”

So What to Do Next?

At their conclusion, the report makes clear that a great deal of additional research is crucial if electronic monitoring is going to be turned into a positive tool.

“The express purpose of California’s juvenile justice system is to promote the correction and rehabilitation of youth,” they wrote. “Yet without the benefit of evidence-based research, judges and policy-makers do not have the tools necessary to determine whether there are rehabilitative effects to these programs or whether, to the contrary, these programs are overly punitive. Such evidence-based research will lend weight to those advocating for the reform of juvenile electronic monitoring programs and the elimination of the least effective and most punitive rules.”

In particular, the report urged future researchers to probe and analyze “the experiences of youth and their families, along with the observations of judges, as well as juvenile probation officers charged with running electronic monitoring programs.” This drilling down “will allow for a more thorough analysis of how best to tailor electronic monitoring programs to fit the needs of youth.”

Part of the problem, said Weisburd, is that—due to the lack of research of the programs—there is little in the various counties’ rules “that allows for tailoring to the needs of each individual child.” Instead, she said, “the approach now is one size fits all.” This is likely, in part, she said, due to the fact that, in many counties, “the rules were just lifted from the counties’ adult systems,” and not modified for the needs of young people.

“Yet, amazingly, this issue has flown largely under the radar,” said Weisburd, “that’s why I think this report is so important.”

*Sam’s name has been changed for his privacy.

Several years ago I was assisting Homicide investigators with a death notification to the parents of a murdered gang member, It wasn’t just a death notification, but we were also there to gather some information. One of the investigators told me I’d get one of two reactions from the parents. One reaction would be the falling to their knees, agonizing cry, the shock and disbelief. The pain that would be so bad it could possibly cause a heart attack or fainting. The second type of reaction would the long sigh, then the thank you for the notification. It would seem as if they expected it. What I found after assisting on a few of these over the course of my career was the second reaction seemed more common from parents who had tried just about everything to keep their son or daughter out of trouble, but had a realistic idea of where the trouble would likely lead. It almost seemed as if they were relieved they’d no longer have sleepless nights waiting for the inevitable knock on the door.

Electronic monitoring might not be the best solution, but it does keep the juvenile at home, hopefully away from other troubled youth and away from victimizing others and or becoming a victim themselves. It may also keep investigators bearing bad news and asking questions about their dead child’s friends from knocking on the door.

MAD, witness LA isn’t into the whole victims of violent crime thing. Witness LA is into the victims of the racist system thing. In this world criminals are the true victims and the system , especially law enforcement, are the bad guys. Notice the way the criminals are quoted as if there speaking the truth without any question or doubt, while it’s taken for granted that the probation officers are racist. Typical Witness LA story.

EDITOR’S NOTE

Thank you for your extremely thoughtful comment, “Mutual Assured Destruction.”

I understand what you mean about those death notifications for parents. In my gang reporting years I witnessed a couple of those. There was one scream I’ll never get out of my head and heart. I also spent time with parents whom I’d gotten to know well, who got that news. I remember one mother said, “At least I’ll know where he is now.” Other parents just shattered.

One night, two other neighborhood women and I sat with a mother we knew in the emergency room of White Memorial Hospital for hours, hoping to get her in on a 5150 because she was threatening to kill herself and her younger son was frightened out of his mind. There’d been another murder of another young man, and it brought up all the pain of the murder of her own son earlier that year, and she broke to pieces. We got her through that night. But those wounds never leave, of course.

About the GPS, I think it could be a valuable program. It just doesn’t seem to be all that well thought out. Yet I got the feeling that it could be reformed.

Thanks again for your thoughts.

C.

Now that we got the mandatory virtue signaling out of the way guess we can all agree it’s a good idea to keep tabs on these little criminals, probably even save some lives. Nice 180

Celeste’s comments goes along with the sidestep she did years ago when I asked her why she was so into gangsters and she said it was a long story. I think she romanticizes this life style or something akin to it, I truly do. As if they’re guardians of their neighborhoods when they truly bring nothing but death and misery.

Hitting the virtual like button on “sure fire’s comment”. BTW I always thought the family members who acted out the most when “lil whatever” met his fate where the most complicit and enabling.

The admitted purpose of the electronic monitoring is to avoid placing the juvenile into custody.

Is that because juvenile custody is a negative experience which should always be avoided or is it because the local govt. wants to minimize expenditures for juvenile custody?

A successful juvenile custody program would seek to facilitate the development of self-awareness and self-control by the individual juvenile.

If any particular juvenile custody program is truly success oriented, a sufficient period of time is still needed before any significant and lasting progress is made.

A juvenile cycling in and out of custody for short periods is unlikely to benefit from any therapeutic programming made accessible.

In that case, the strategy may be to provide a sufficiently negative experience which can deter the juvenile from repeating prohibited behavior.

When arbitrary technical violations of an electronic monitoring regime trigger a treadmill between home custody and juvenile custody facility,

then the juvenile is simply a case number processed within a self-preserving bureaucracy whose dial is set for mediocrity and intellectual dishonesty.

That creates a risk the system will function as a training ground to prepare the juvenile for cycling in and out of the adult custody system.