Two new reports from The Sentencing Project reveal that while the number of kids in juvenile carceral facilities in the United States has dropped exponentially over the last 20 years, there are still thousands of people serving life sentences after being convicted of crimes as minors or young adults.

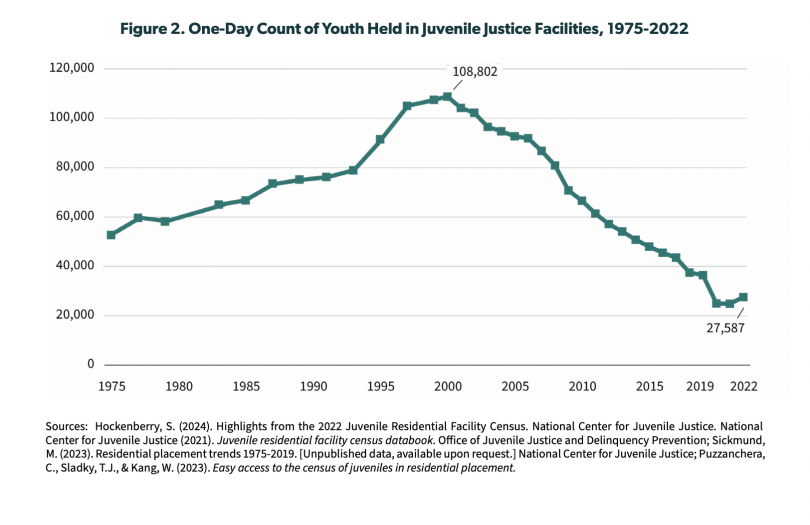

In the first report, data analysis shows that the number of youth locked in juvenile facilities on a typical day fell 75% between 2000 and 2022, from 108,800 to 27,600.

Between 2000 and 2018, just 5% of youth arrests were for crimes the FBI categorizes as Part 1 violent crimes (murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault). The proportion increased to 8% in 2020, when youth arrest rates were at their lowest.

“Public opinion often misconstrues the realities of youth justice, wrongly assuming that crime is perpetually increasing and that youth offending is routinely violent,” said report author Joshua Rovner, Director of Youth Justice at The Sentencing Project. “This report dispels those myths. The 21st century has seen significant declines in youth arrests and incarceration, and youth offenses tend to be nonviolent.”

Black youth are still far more likely to be held in the juvenile system than their white peers, the data shows. In 2021, Black kids were incarcerated at 4.7 times the rate of white kids.

Approximately 228 per 100,000 Black minors and 181 per 100,000 Tribal youth were incarcerated, while 49 per 100,000 white youth and 13 per 100,000 Asian youth were locked up. Latino kids were locked up at a rate of 57 per 100,000. Kids labeled multiracial were incarcerated at a rate of 40 per 100,000.

These numbers do not include minors held in adult jails and prisons. In 1997, there were 14,500 minors in adult facilities. By 2022, the number had dropped to 2,337. One troubling statistic emerged from this data, according to Rovner. Out of those 2,337 kids, 437 were serving sentences in adult prison in 2022 — a 50% increase over the previous year.

“Though this population is small in number, this one-year rise represents a reversal of a 25-year trend,” Rovner wrote.

The data points to the importance of diverting kids away from the criminal court system and toward alternatives that help lower recidivism and offer better outcomes for youth.

Locked up for life for youthful crimes

Another noteworthy August report from The Sentencing Project, digs into the issue of people serving life in prison or “virtual” life lasting 50 years or more after being convicted of committing crimes when they were minors or young adults.

Over the last decade, reforms have drastically limited the number of minors serving life in prison without the possibility of parole (LWOP) across the nation.

In 2012, nearly 3,000 people were serving juvenile life without parole, according to report authors Dr. Ashley Nellis and Devyn Brown. As of January 2024, 87% of those individuals had been resentenced and 1,070 had been allowed to return home, largely due to a set of U.S. Supreme Court rulings that blocked states with mandatory life without parole sentences for homicide convictions from sentencing kids to LWOP. Most juvenile LWOP sentences, according to Sentencing Project research, had occurred in states where judges were not allowed to choose a less severe sentence.

Still, there are thousands of people serving other sentences that will likely keep them behind bars for all or nearly all their lives for juvenile crimes.

In 2020, more than 8,600 imprisoned people had been sentenced as minors to either life with the possibility of parole (LWP — not to be confused with LWOP) or 50 or more years behind bars.

In California, the state with the largest portion of these sentences, 2,358 people were serving LWP or virtual life in 2020. The states with the next largest populations were Texas (1,081), Georgia (900), and New York (461).

In Georgia, as well as Alabama, Louisiana, Maryland, and Mississippi, 80% of the people serving juvenile LWP or sentences of 50-plus years were Black.

There are thousands more people in prison who were sentenced to LWOP when they were young adults between the ages of 18-25. And the racial disparities persist in this population of incarcerated individuals as well.

The Sentencing Project’s data revealed that two thirds of young adults serving LWOP sentences were Black.

“Despite the reality that people “age out” of criminal activity as they approach adulthood, jurisdictions impose lengthy and life sentences for young people under the misconception that long sentences serve a deterrent, rehabilitative, or retributive function,” the report authors write. “Yet recidivism among those resentenced and released from life sentences is rare.”

Moreover, research shows that “emerging adults” between the ages of 18-25 are still developing, and have maturity levels more similar to kids under 18 than to older adults.

The report points to a handful of reforms in different states that take the developmental status of minors and young adults into consideration. One law, the Juvenile Restoration Act, enacted in Maryland in 2021, authorized courts to review and consider resentencing in all cases in which minors were sentenced to more than 20 years.

In Illinois, people convicted of most types of crimes (except those with LWOP convictions) are eligible for parole review after 10 or 20 years in prison, if they were under 21 at the time of the crime. The state also ended the use of LWOP sentences for youth under 21 in most cases, allowing sentence review after 40 years.

And in California, “youthful offenders” convicted of crimes that occurred when they were adults under the age of 27 — and who were not sentenced to LWOP — are eligible for parole review within 15-25 years.

The report authors recommend states take these reforms further. “As policymakers design reforms for the criminal justice system, these changes should align with neurobiological research and encompass all forms of life imprisonment and extreme sentences,” Dr. Nellis and Brown write. “Youth and emerging adults who committed crimes during adolescence should receive a sentence review within the first ten years, with a rebuttable presumption of release after fifteen years.”

Great article!! Thanks for the story

thank you for this news i appreciate it alot.