On January 18, at the front of an immense classroom, within the North County Correctional Facility—one of several jail facilities that make up Pitchess Detention Center in Castaic, California—a crowd of approximately 200 watched 38 men in shiny black graduation gowns walk across a stage to receive high school diplomas and vocational certificates.

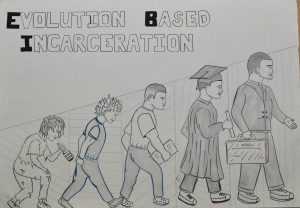

The 38 inmates made up the largest graduating class since the 2012 launch of Los Angeles County Sheriff Department’s Education Based Incarceration (EBI) program, through which Five Keys Charter School operates in the county’s jails.

Within the immense classroom, just down the hall from an impressive library with a vibrant ocean mural painted by fellow inmates, the students, who ranged in age from young adults, to much older men with graying hair, sat with looks of nervous anticipation as they waited for their names to be called.

Teachers and school administrators filled the seats directly in front of the stage, shouting and cheering along with the students and their family members as each grad walked down the aisle to accept their diplomas and shake the hands of a lineup of school administrators and members of the LA County Sheriff’s Department who facilitate the education program.

“It feels amazing,” said Karaym, one of three students who gave graduation speeches. “It feels like it was a long time coming.”

When Five Keys Charter School set up shop inside San Francisco County’s jails in 2003, it became the first charter high school inside a jail system in the nation. Former Los Angeles County Sheriff Lee Baca brought the charter school to Los Angeles in 2012.

In addition to high school classes, students in the jails can participate in life skills classes, parenting classes, violence prevention courses, restorative justice classes, and vocational programs that aim to improve reentry outcomes.

In 2013, a RAND Corporation study found that inmates who participated in education programs behind bars—like LA County’s EBI–had 43 percent lower odds of recidivating than inmates who did not participate. The study—a meta-analysis of 30 years of research on education behind bars—also found that inmate students were 13 percent more likely to gain employment after their release than their peers who did not take part in education programs while incarcerated. For vocational certification students, the success rate was even higher. Those who participated in vocational training programs “had odds of obtaining post-release employment that were 28 percent higher than individuals who had not participated,” according to RAND. And, of course, by lowering recidivism rates, these programs save states and local jurisdictions money.

Students who start working toward completing their education through EBI can continue the program at Five Keys community sites if they are released before they finish, said Margot deGrave, one of the school’s principals. “In LA County alone, we have 30 community sites.” In addition to helping keep students exiting jail on track to finish high school, the sites help students with other barriers to successful reentry—connecting them with employment programs, housing services, and other resources.

Students who start working toward completing their education through EBI can continue the program at Five Keys community sites if they are released before they finish, said Margot deGrave, one of the school’s principals. “In LA County alone, we have 30 community sites.” In addition to helping keep students exiting jail on track to finish high school, the sites help students with other barriers to successful reentry—connecting them with employment programs, housing services, and other resources.

The Five Keys educators’ dedication shows.

Karaym and the two other students who gave speeches during the ceremony each mentioned several teachers by name, thanking them for their kindness, their encouragement, and for not giving up on them.

A teacher in the audience told WitnessLA about one man in her class who, when he found out that he was being transferred to another jail, assured her that he would finish his schooling, and begged her to come to his graduation. When the young man saw her face in the crowd several months later, he lit up. “You came!” he said, beaming. That show of support meant the world to him, the teacher said.

The educator explained that she had been working in the jails for decades, and that there was no more rewarding work than helping the locked-up men realize their potential and “their value” as human beings. The students, she said, are so grateful for the support of teachers and the sheriff’s department members committed to helping them achieve educational success.

Karaym, too, said he was surprised by all “the love” he felt while giving his speech. “I was shaking up there,” he said.

He was startled, Karaym said, when the audience applauded and cheered with such obvious enthusiasm for the graduates. “We live in an atmosphere where people say, ‘You’re not going to make it.'” Yet, on this day, things were different. “People are rooting for you.”

Since he started school at Five Keys, Karaym said there have been deputies, “who tell us on a daily basis, ‘You’re wasting your time.'” The young man said he was proud to prove the skeptics wrong.

“Diamonds start off as dirt,” Karaym said.

Speaking before the graduates, EBI alumni Joe Hernandez told the story of his childhood, in which going to prison was a rite of passage—one that meant that you were a “big G.” But EBI steered him down a different path, Joe said, one that several years later, has helped him get into a competitive master’s program. “I’m still a ‘G,'” Joe said. “It just changed: I’m a graduate. I’m in a graduate program.”

“Thank you to the sheriff’s department—I never thought I’d say that,” Joe added, drawing laughs from the crowd.

This year’s graduates also thanked the sheriff’s department for facilitating the education program.

The students who gave speeches also expressed deep gratitude to their parents in the crowd. Robert, a 43-year-old father, cried as he thanked his mother for being his “number one supporter” through this “difficult situation.”

“I will not rest until I am the one you can forever count on,” Robert said, quietly sobbing. Robert said that he hopes, too, that his efforts will show his children that “no matter the falls we take in life, it’s how we get back up that counts.”

Karaym, who is in his early 30s, said that he wished his parents were able to see him graduate. His father, an English teacher, and member of the Peace Corps, pushed him to take his education seriously. But the Peace Corps frequently moved Karaym’s family across the world, and the constant uprooting made it hard for him to make or keep friends, and to care about learning, he said.

“I used to hate my dad for it,” Karaym said.

And his anger made him act out and led to trouble with the law, according to Karaym.

While each student was allowed to invite one family member to the graduation, traveling is difficult for Karaym’s father, who, because of an aneurysm, now has cognitive impairments. His mother, who is now both a caretaker for her husband and the sole earner for the family, was also unable to attend.

“I always told my mom, ‘I’m going to change, I’m going to change,'” Karaym said. “She told me, ‘I’ll believe it when I see it.’ This time, Karaym said, he made sure that his actions matched his words.

When asked what motivated him to finish this time, Karaym said, without hesitating, “My unborn children.”

“How am I going to be able to tell them to reach for something that I was unable to reach for myself? How am I going to tell them to reach for their dreams?”

Karaym said that he also completed his education for his family. “In my culture, I’m supposed to be taking care of my mom, and here I am still acting like a kid,” Karaym said. “This is my first step toward changing all of that. I have a lot of work to do. My age is catching up with me.”

After the ceremony, the students, still wearing their gowns and hats, and now armed with their diplomas, lined up in front of a gray backdrop, waiting to have their photos taken with the family members they had invited. One student lifted his arm to put it around his father before hesitating and, with a worried look on his face, asking the deputy behind the camera, “Can I hug him?”

“Yes, of course,” the photographer said.

All images by LASD Deputy Lillian Peck.

Great to see LASD in a positive light.

I worked at NCCF in the early 90’s and we had the same program under a different name with the Hacienda-LaPuente School District – yes with graduations and all. Lee Baca didn’t begin the program, he just rebranded it for his own self-aggrandizement.

The Sheriff’s Department has been doing these things for years without fan-fare, nor “credit” for doing the right thing. No real news value in that.

YUP!!

Just pre-election Department “positive” high points and fodder for the voting public. I’m just waiting for a major pre-election scandal to hit that none of the LASD executives can claim ignorance, deniability on, run from or scapegoat a subordinate for.

Oh the scandal is coming…..just wait. Can’t hide this one……..However, great for these inmates.

Sooooo to hell with employee’s troubled by life issue’s but big investment’s into inmate’s for the corrupted dept.’s personal agenda of showing that they aren’t as screwed up internally as they appear to be? Haaaaaa #cantwin

Do tell. Now living in the Rockies post-retirement, I’m out of the loop.