By the Staff of Counseling@NYU

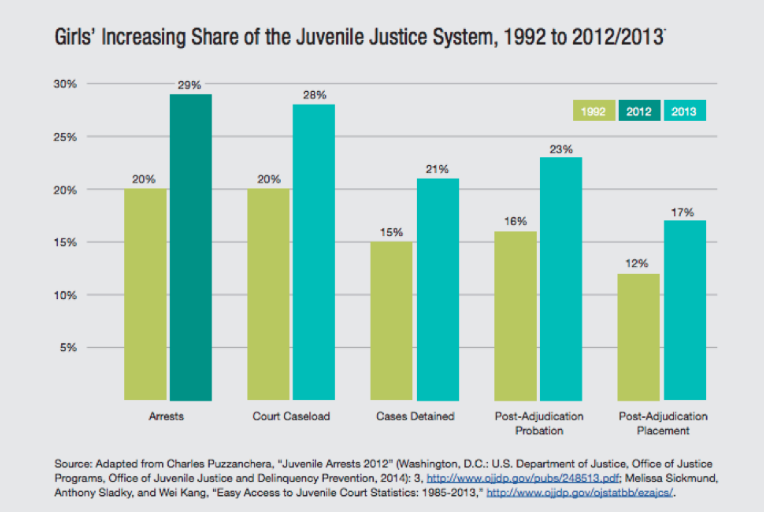

Arrests of youth younger than 18 are down significantly. Between 1994 and 2014, juvenile arrests dropped from about 2.8 million to about 1 million, according to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP). But for girls in this same age group, who account for about a third of juvenile arrests, the trend is moving in the opposite direction. Between 1992 and 2012, the share of arrests for girls increased 45 percent, according to a 2015 report from the National Crittenton Foundation, a Portland-based organization that works with girls in the criminal justice system.

Why the discrepancy? The juvenile justice system was designed for boys, many experts say.

“The system doesn’t know what to do with girls who engage in gender nonconforming behaviors. Social norms suggest that girls aren’t supposed to defy parents or leave the house without permission,” said Shabnam Javdani, assistant professor of Applied Psychology at NYU Steinhardt. “But because of the ‘boys will be boys’ mantra, boys engaging in the same behaviors won’t be looked at as particularly deviant.”

Javdani believes the criminal justice system needs to better recognize why girls engage in behaviors that lead to arrests. Understanding their environments, she said, could be the key to keeping them out of the juvenile justice system.

A System Created for Boys

According to Javdani, who also serves as a faculty member with Counseling@NYU, which offers an online master’s degree in mental health counseling, the juvenile justice system has prioritized preventive or diversion-related tactics when dealing with young people who commit offenses that would not be criminal if they were over 18 — including running away from home or breaking curfew. But, because most diversion programs are designed for boys, many young girls don’t respond to them or don’t want to participate in them. Part of the reason these programs aren’t effective for girls is that many girls enter the criminal justice system for different reasons than boys.

“Many of the youth, both boys and girls, involved in the legal system have trauma histories, but [some] girls have much more complex and much more severe histories of trauma,” Javdani said.

The Crittenton report noted that girls in the juvenile justice system have consistently reported higher rates of adverse childhood experiences such as sexual abuse, family violence and neglect. A systemic misunderstanding of the root causes that lead to “acting out” behavior can create a disconnect that limits the effectiveness of prevention or diversion programs.

Jessica Grimm, who serves as executive director of Bravehearts MOVE (Motivating Others through Voices of Experience) New York, a peer-led youth movement that works with youth in New York state’s child welfare and juvenile justice systems, noted that adults working in these systems sometimes give up on girls because of their perceived lack of interest or disrespectfulness.

“If the young person doesn’t want to talk to people or doesn’t want to engage, they say ‘You know if you’re not going to talk to me then I’m just going to leave you,’ ” Grimm said. “Young women really need patience, understanding and also positive role models.”

In response, the juvenile justice system relies on harsher sanctions to “teach them their lessons,” relabeling what would otherwise be noncriminal acts, which are only offenses because the girls are younger than 18, into more severe offenses that draw girls more deeply into the justice system and can lead to detention.

Javdani explained that when a girl runs away, for example, officers may ask the family what the circumstances were under which she ran away. The parents might include in the response that she shoved her little brother out of the way when she left while they were trying to stop her.

“So what the system might now focus on is that shove, and that girl will now get labeled as having engaged in a simple assault,” Javdani said.

OJJDP estimates that in 2013 about 37 percent of girls’ detentions were for offenses that would not be criminal if they were older than 18, while 21 percent were for simple assault and public order offenses.

Changing the Context, Not the Girl

To help address the specific needs of young girls involved in the criminal justice system, Javdani created NYC Resilience, Opportunity, Safety, Education, Strength (ROSES), External link a community-based intervention program that pairs young girls with highly trained, advanced undergraduate students at NYU who serve as their advocates.

Each girl in the program identifies a specific goal she would like to achieve — from career-oriented objectives to creative and artistic ambitions. Advocates work with the girls individually for 10 to 12 weeks to identify challenges or barriers within their environments and to secure meaningful connections to informal and formal community resources that will support her in achieving those goals.

“The whole model is to really meet people where they are at,” said Genevieve Sims, who served as an advocate and now works as a program coordinator and supervisor for a peer-led iteration of the program. “You are not there to be a therapist. You’re there to really be a mirror or a sounding board for them to consider what do they need and what do they want.”

For example, a girl in the ROSES program whose goal is to perform better academically may have experienced sexual assault at school. With her permission, her advocate can help to make school administrators, counselors and teachers aware of the situation, and develop plans to help ensure that the girl feels safe. The advocate may work to create a buddy system for the young girl, to make certain that the person who assaulted her is not in any of her classes, and ultimately make the school a place where other young girls who experience sexual assault feel empowered to discuss their experiences and stand up for themselves.

“We look at the school’s policies and practices and really critique that context as opposed to asking why is it that this girl is not coming to school all the time,” Javdani said. “The overarching aim is to provide a very short term, very intense and contextually centered intervention that will ultimately leave the girl with self-advocacy skills.”

Sims added that allowing the girls to choose what they want to work on is a key component of the program’s success.

“The beauty of it is the individualization and the individual space that you can create when somebody believes you are hearing them in an unconditional, nonjudgmental way,” Sims said.

Expanding to Peer-to-Peer Support

Although Javdani is still studying its effectiveness, ROSES has already launched a sister program ROSEbuds that encourages women who have entered the juvenile justice system as girls to serve as peer advocates. ROSEbuds was created as part of the New York State Girls’ Justice Initiative (GJI), in collaboration with the New York State Permanent Judicial Commission on Justice for Children, which aims to identify gender-specific, trauma-informed best practices for working with girls at-risk or involved with the juvenile justice system and to implement those practices across the state.

In collaboration with the GJI, the White Plains Youth Bureau and Bravehearts have partnered to run a version of this program, and Grimm said having role models and advocates who can relate to girls’ situations helps to break down barriers for skeptical youth.

“Young adults, both male and female, are more receptive to listening to and building relationships with people if they feel that the individual has walked in their shoes and has similar experiences,” Grimm said. “They feel like ‘I know I can trust you or listen to you because you speak my language and you’re from my community.’ ”

But Grimm noted expanding the new program would take buy-in from those in the criminal justice system itself, not just from girls in that system.

“We need to really find creative ways to get the justice system to invest into the ideology of peer-support advocacy,” Grimm said. “I’m looking at a young woman in a lens of her whole situation rather than just the behavior or alleged behavior that brought her to the justice system.”

It’s that lens that Javdani hopes the justice system will begin to use to see girls for the potential that they have to contribute in a positive way to their communities.

“These are girls who are activists, who want to be part of the social change agenda,” Javdani said. “They are articulating goals for their younger siblings and for younger girls that they see who might be going through the same things as they are — goals that really benefit the collective good.”

Counseling@NYU, the online masters in mental health counseling from NYU Steinhardt.

Images: National Crittenton Foundation, “Gender Injustice: System Level Juvenile Justice Reforms for Girls”

I have to point out the obvious: what planet are these “experts” referring to? In Los Angeles, short of a minor killing someone, robbing someone at gunpoint, or a similar violent felony offense, the entire premise of this article is non-applicable.

I’m sure Pearl Fernandez was a “girl” before becoming a “women” who brutally killed her son in the Antelope Valley and was put in a jail for “men”. How strange is that.