by Chandra Bozelko

On December 8, 2022, a jury convicted the former warden of the Federal Correctional Institution-Dublin located in Alameda County, CA, of eight crimes. Ray J. Garcia, the former warden, was convicted of three counts of having sexual contact with an incarcerated person, four counts of abusive sexual contact, and one count of lying to FBI agents.

The news of a warden abusing his power is disheartening. But, it is far more disturbing to learn that, when Garcia engaged in his criminal behavior, he was also serving as the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) coordinator for the same low-security women’s prison known as FCI-Dublin.

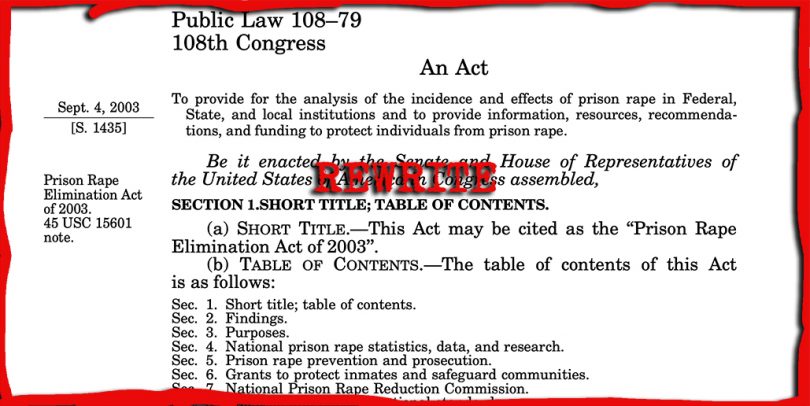

In other words, he was the point man responsible for assuring compliance with the federal statute that promises to “provide for the analysis of the incidence and effects of prison rape in federal, state, and local institutions and to provide information, resources, recommendations and funding to protect individuals from prison rape.”

According to his federal indictment, one incident in which he groped a woman occurred while PREA auditors were on site conducting their audit.

The results of that 2021 audit have never been made public. Congress requested the report but, inexplicably, it never materialized. Another audit was conducted at the same prison in March 2022, after eight members of the US Congress insisted that the report on the matter be turned over to them by the end of the month.

When the audit finally arrived it certified that FCI-Dublin was in compliance with PREA.

Garcia’s trial and conviction once again showed how entrenched sexual violence is in the nation’s prisons for women. It also exposed the failure of the accountability system built into the Prison Rape Elimination Act, which was passed unanimously by both parties of Congress, and signed into law on September 4, 2003, by President George W. Bush, its goal is to eradicate rape and sexual abuse of incarcerated people in all types of correctional facilities in the U.S.

It is also the only statute that makes sexual contact between staff and those incarcerated nonconsensual as a matter of law.

Nine years after PREA was enacted, a committee formulated 45 National Standards to “Prevent, Detect, and Respond to Prison Rape” (PREA Standards)

These standards require all correctional facilities to be examined at least once during every three-year audit cycle. Audits have three components: an in-person site review, interviews with incarcerated people inside the facility, and review of the various documents that PREA requires the prison to maintain. The first two requirements could not be conducted remotely during the pandemic.

As of 2021, approximately 332 auditors — down from about 500 auditors in 2017 — conduct inspections of correctional facilities around the country. As of summer 2021, 6095 such audits are in the books.

Yet, after several reports by those inside the various facilities that many of the conclusions in the audits were egregiously inaccurate and ignored complaints of rape by prison residents, Congress amended PREA in 2018 through the U.S. Parole Commission Extension Act. The amendment allows decertification of auditors when their reports don’t match the conditions and practices within a prison.

Fortunately, while there were concerns about the new decertification process, it doesn’t appear to be totally futile. The number of certified auditors has been reduced, and there are consequences for auditors who fail to record relevant information on the final audit report.

One such instance of accountability suggests that justice officials are taking the certification of auditors seriously.

Vic Killion, an auditor employed by the Nakamoto Group —the same company that the United States Inspector General found to have conducted insufficient review of immigration facilities it was retained to inspect — audited and approved the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn in June 2017.

Yet, a month before auditor Killion’s report, the United States Attorney’s office for the Eastern District of New York indicted and arrested three staff members for repeatedly and violently sexually abusing at least six women in custody in the Brooklyn facility. The post-arrest audit by Vic Killion, however, found only 5 allegations of sexual abuse, all of which it deemed to be “inmate on inmate.”

In response, the Department of Justice decertified Killion in 2019 for “misapplication of PREA standards.”

But, while the decertification by the DOJ was the correct response, Killion’s case deserves closer scrutiny. In 2017, the same period in which he was supposedly touring the U.S. and scrutinizing prisons, according to public records of public employees’ salaries, Killion was also employed as a “jailer” in Clay County, Indiana. A jailer is another word for a guard, a class of workers who have been found to be suspicious of reports of abuse by those they’re guarding.

Assuring integrity in this corps of inspectors is part of what is required to make PREA work, but it isn’t all of it. The design of the audit demands more attention, as well. At present it seems almost deliberately structured to omit criticism of the facility.

On the surface, it would appear otherwise because PREA requires auditors to interview at least a few of the residents of the facility they are examining. Yet, when it comes to the resulting report, there is no requirement to quote from or in any way memorialize what those incarcerated people said.

Worse, if there are allegations of sexual abuse having occurred at the facility, auditors have no obligation to interview the actual victims. And even if the auditors are proactive enough to do so anyway, as with the random interviews, there is no requirement to reproduce any part of what the victims said. Instead, the incarcerated people questioned have their responses summarized and interpreted by the auditor in the final report.

For example, in the 2017 PREA Audit for FCI-Dublin, auditor James Roland – who is also employed by the same Nakamoto group that sent jailer Killion into the New York prison — reveals that he interviewed a total of 28 incarcerated people. But, in the final report, he summed up what the subjects of his interviews told him as follows: “The inmates interviewed acknowledged that they received information about the facility’s Zero Tolerance policy against sexual abuse/sexual harassment immediately upon their arrival to the facility, that staff were respectful, and that they felt safe at the facility.”

Twenty-eight voices weighed in during this audit. To the extent that four of them identify as transgender, and the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates the prevalence of sexual violence against this particular population as close to 33%, it’s difficult to believe that every incarcerated interviewee gave the place — a prison that is known as the “rape club” – rave reviews.

In the course of his review, the auditor noted four allegations of sexual abuse. Yet, his response to these allegations was to examine the prison’s investigative files and confer with the staff about the alleged incidents.

He did not, however, interview the person who had reportedly experienced the abuse.

And, as mentioned earlier, astonishingly, none of the PREA standards require that an auditor talk to an alleged victim, if the auditor learns of one.

Similarly perplexing omissions have played out in other PREA reports on other federal prisons. An auditor visiting FCI-Coleman in Florida didn’t talk to the incarcerated women at all, in direct violation of the PREA Standards.

PREA is coming up on its 20th birthday next year. Its implementation has been sluggish and imperfect to say the least. It took almost a decade after its passage to come up with the standards for the audits required by the original statute.

And since those PREA Standards went into effect in ten years ago, the Bureau of Justice Statistics has published only one report of reliable data on sexual violence in prisons.

The report, titled “Sexual Victimization Reported by Adult Correctional Authorities, 2016-2018,” was released in 2021 and covered —as the title suggests—the years from 2016 to 2018.

As for the rest of the years between 2012 and 2021, no reliable data on the incidence of sexual assault and harassment has been made available to the public at all.

And, now, two decades after the statute was signed into law, we still don’t have any kind of functional best practices to guide its implementation.

So, the bottom line is this: Before PREA turns 20, it needs a rewrite.

Author Chandra Bozelko is an expert on a broad number of issues related to criminal justice reform. She also has personal experience with the topic.

A magna cum laude graduate of Princeton University, Bozelko was in the middle of postgraduate study in law and public health when she was arrested for non-violent crimes that remain on appeal. She served more than six years at the York Correctional Institution, Connecticut’s state-run women’s prison.

While locked up, Chandra was the first inmate to write a regular newspaper column from behind bars. Her prize winning column, “Prison Diaries,” has been followed, since her release, by a book of poetry, and commentary for such publications as The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, The New York Times Magazine, USA Today, US News and World Report, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, Elle, Ms. Magazine, The Guardian and more. As she wrote, Bozelko continued to gather prizes.

Now we are happy to announce that Chandra Bozelko is beginning a regular column for WitnessLA called “Inside Job.”

So…stay tuned. You won’t want to miss anything she has to say.

This was beautiful Admin. Thank you for your reflections.