HIGHLY CRITICAL INDEPENDENT REPORT INTO ORANGE COUNTY DA’S OFFICE SCANDAL CALLS FOR STATE OR FEDS TO INVESTIGATE

In the newest twist in the ongoing Orange County District Attorney jailhouse snitch scandal, an independent panel issued a report calling the OC DA’s Office “a ship without a rudder” suffering from a “failure of leadership.” (Here’s the backstory on the OCDA and the OC Sheriff’s Department’s use of jailhouse informants and withholding of evidence from defendants.)

The 24-page report, which followed a six-month probe by the Informant Policy & Practices Evaluation Committee, a panel comprised of a retired judge and attorneys hand-selected by DA Tony Rackauckas, calls for a state or federal investigation of the DA’s Office.

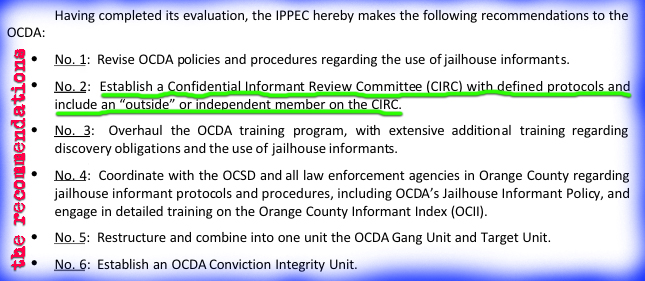

The report recommends reorganizing the DA’s Office, creating a Confidential Informant Review Committee to oversee the use of informants, and a Conviction Integrity Unit to investigate innocence claims. The report also calls for the appointment a retired judge to monitor and publicly report on how the OCDA is complying with the panel’s findings.

Following the release of the independent report, embattled OC DA Tony Rackauckas publicly agreed to most of the recommendations, saying some were already being implemented. Rackauckas also sent a letter to US Attorney General Loretta Lynch welcoming a Department of Justice to initiate any review deemed “appropriate in regard to the OCDA Informant Polices and Practices.”

The Voice of OC’s Rex Dalton has more on the panel’s findings. Here’s a clip:

The Informant Policy & Practices Evaluation Committee supported calls by national legal authorities for an investigation by either the U.S. Department of Justice or the California Attorney General’s Office. At minimum, a grand jury should look into the issue. Such an investigating agency should have subpoena power and the ability to call witnesses to testify, said the report dated Dec. 30, 2015.

“The confidence of various constituencies in the prosecution of criminal cases in Orange County that involve the use of jailhouse informants has eroded,” the report continued, noting constituencies included private attorneys, prosecutors, judges, and families of both victims and the accused.

“What also became clear during the evaluation was that, in many ways, the OCDA’s office functions as a ship without a rudder. This failure appears to have contributed to the jailhouse informant controversy.”

At a press conference this afternoon, Rackauckas and his staff largely greeted the report with acceptance, agreeing to most recommendations and/or noting such enhancements already were under way.

He said he as open to an federal investigation, but that he believed his office and done nothing wrong and such a probe would confirm that.

When asked directly if he plans to resign he said: “As far as resignation is concerned, certainly I am responsible, but no I don’t intend to resign.”

[SNIP]

The evaluation panel interviewed some 75 members of the DA’s office, defense attorneys, and law enforcement, along with reviewing multiple case briefs and documents on informant probes in other regions.

From this, the evaluators said: “It became clear that over the years some prosecutors adopted what the [panel] will refer to as a win at all costs mentality. This mentality is a problem.

“Stronger leadership, oversight, supervision and training can remedy this problem. Key to addressing the problem is changing the culture of the office by not rewarding prosecutors with the ‘must win’ mentality with promotions.”

Evaluators were also told that prosecutors were subjected to inappropriate pressure by law enforcement officers seeking prosecutions in questionable cases.

This was compounded by the fact that deputy district attorneys were “embedded” in law enforcement agencies, with deputy district attorneys and officers developing social relationships that could compromise independent prosecutions.

“[Evaluators] heard from numerous deputies that it is not uncommon for deputy [district attorneys] to be subject to inappropriate pressure from their law enforcement counterparts to file cases that the deputies were otherwise not comfortable filing,” the report states.

“The [panel] heard reports of deputies being ridiculed and even harassed by law enforcement for not being aggressive enough in filing certain gang cases.”

SANTA CLARA SCRAMBLES TO PROVIDE MUCH-NEEDED PSYCHIATRIC BEDS FOR KIDS IN CRISIS

In Santa Clara County, NorCal’s most populous county, parents seeking emergency mental health care for their children have to travel an hour or more (sometimes hundreds of miles) to the nearest cities with open psychiatric beds for kids and teens.

Santa Clara does not have one single inpatient bed for kids suffering from a mental health crisis, according to San Jose Mercury News’ Karen de Sá.

The Santa Clara Supervisors have plans to fund a desperately needed psychiatric facility by June for the county’s children, 600 of whom seek out-of-county inpatient mental health care each year.

De Sá, whose powerful five-part series on the excessive and unchecked use of psychotropic meds on California’s foster children sparked legislative action, has more on the issue. Here’s a clip:

…as many as 20 county youths are in far-flung psychiatric hospitals on any given day suffering from deep depression, excessive anxiety, self-harming behaviors and other episodes of psychosis. More than 600 of the county’s children seek inpatient treatment outside of the county each year, since the only local facility shut down about 20 years ago.

And because hospital stays typically last about a week, parents struggle to visit while caring for other children, maintaining jobs and traveling for hours each day if they cannot afford to rent hotel rooms.

In recent months, a group of mothers has lobbied county supervisors to solve the problem, which has persisted for years but was not acted upon by county officials until Supervisor Joe Simitian took up the cause a year ago.

Proposals for an inpatient unit serving 5- to 17-year-olds will be solicited in the coming weeks, with a provider selected by May. So far, no details about possible locations or cost are available.

Sarah Gentile, of Los Altos, scrambled to get crisis care for her teenage son to get him through his severe depressive episodes. In 2014, when the 17-year-old revealed to his psychiatrist that he had a suicide plan, a doctor at El Camino Hospital’s emergency room in Mountain View had some troubling advice.

“The first thing he said to me was: ‘We need to call around and find a place that will take your son,'” Gentile recounted. “I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ And he said, ‘We don’t have any psychiatric beds for children here.'”

There is one program, run by the nonprofit EMQ FamiliesFirst, offering seven emergency beds for psychiatric patients in a county that is home to more than 430,000 young people age 17 and younger. But the EMQ beds can be used for only 24 hours.

At Gunn and Palo Alto high schools alone, teens were hospitalized 50 times last year for being a threat to themselves or others. In 2014 and 2015, one former and three current students took their own lives. Those deaths followed six similar cases in 2009 and 2010 — tragedies that mostly occurred on the Caltrain tracks by the two schools and have terrified local residents.

Hoping to reach youth in crisis who display early warning signs, county officials and community-based providers say a hospital unit would enhance other prevention efforts underway. “Mental diseases and disorders” are by far the number one reason California children are hospitalized, according to the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health — well above fractures, viruses, seizures and asthma. Nearly 40,000 Californians ages 5 through 19 were hospitalized for mental health reasons in 2014 alone.

CALIFORNIA’S INCREASING EFFORTS TO GIVE FOSTER KIDS BETTER OUTCOMES

KQED’s Adizah Eghan takes a look at the difficulties foster kids face as they age out of the system, and California’s new efforts to give foster children better care and hopefully, in turn, better outcomes. Here’s a clip:

In October, Governor Jerry Brown signed a law intended to scale back the use of group homes by the state’s foster care system. Instead of leaving foster youth to the care of the staff in a group home, Assembly Bill 403 (AB 403), will place children more quickly into foster families.

Foster youth will stay at treatment centers for a maximum of six months and group homes will be officially be phased out around 2021. These treatment centers are designed to better fuse the services of the mental health and child welfare systems.

[SNIP]

According to a 2009 Report from the Urban Institute, one in five foster care youth will become homeless after the age 18, and one in four will be involved in the justice system within two years of aging out of the child welfare system. Those numbers prompted California to extend the age foster youth receive benefits to 21.

Twenty-year-old Noel Anaya has been in foster care since he was 4 years old.

“When I was 18, I realized, that I had [this year] plus a year to go. So after high school, [I] figured out a game plan, you know go to college.”

But sticking to a game plan is difficult he says. Foster youth often have to worry about things that might not even cross the mind of a privileged youth who is the same age.

“You go through a midlife crisis at the age of 18, 19, 20, because you’re like, ‘Oh my God is my credit good, is my housing stable, [are] my funds right?”

RECENT OFFICER-INVOLVED SHOOTINGS POINT TO NEED FOR REFORMS TO LAW ENFORCEMENT PRACTICES

An LA Times editorial says that recent questionable officer-involved shootings point not only to the issue of racialized policing, but also to an overall need for changes to outdated policing practices.

Instead of asking whether a fatal officer use-of-force was “objectively reasonable”—a question that should be reserved for deciding whether an officer should be charged with murder—law enforcement and local officials should consider whether an officer could have used different tactics for a better outcome. Here’s a clip:

Fundamental problems in U.S. policing extend beyond the racial and economic patterns that make African Americans more likely to be crime victims, more likely to be arrested and more likely to be killed by police. They implicate basic nuts-and-bolts issues, such as tactics and judgment.

That fact was tacitly acknowledged Wednesday by Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who promised to roll out new training in less-confrontational policing and alternatives to lethal force in the wake of the video of the McDonald shooting and continuing police violence that appears tragically unnecessary, such as the recent shooting deaths of Quintonio LeGrier and Bettie Jones.

Emanuel’s statements, while welcome, are embarrassingly tardy and shockingly inadequate. Police in large American cities ought to be setting worldwide standards for de-escalation, less-than-lethal force and cautious encounters with subjects instead of using military-style, shoot-first tactics. Emanuel should be able to draw on knowledge and best practices compiled by dozens of cities and not put so much stock in Tasers, which also can be lethal. It should be a given that people such as LeGrier’s father or the person who saw Tamir with the toy should be able to call 911 and be answered by professionals well-versed in practices geared toward the safety of suspects as well as themselves and bystanders. But Los Angeles and other cities have only recently begun embracing specialized training to help officers, for example, recognize and deal with mentally ill people and employ other, more modern response protocols.

When police encounters fail — when they result in death — the questions asked in official inquiries are too often limited to whether the officers’ actions were “objectively reasonable.”

That may be the appropriate question when determining whether the officer should stand trial for murder. But decisions not to indict officers (as in the cases of the officers who killed Tamir and Hammond) or not to convict them (as in the hung jury in the first prosecution in Gray’s death) must not be taken as statements that nothing went wrong. The appropriate question for police discipline bodies, chiefs, trainers and elected officials ought to be whether officers had, were aware of and could have used alternatives that were likely to result in better outcomes.